2016, main street of Kerhonkson

Kerhonkson

Spring 2016

A sign of the times

The large green and white New York State DOT “Kerhonkson” sign stood in front of the 1888 Victorian Rhodes house at the intersection of Milton Avenue and Route 9W in Highland for as long as most of us could remember. It directed people to Kerhonkson (NY) via Route 44/55 taking the traveler and large trucks through the hamlet of Highland, then southwest to Gardiner, over the Shawangunk Mountains, and eventually to the once thriving tourist area known as “Kerhonkson.” To the relief of every resident or business owner in Highland, the sign was removed in 2002. To the disbelief of many, the historic Rhodes House went with it in a 9W improvement project. Today the site is a Veterans’ park featuring war memorials. Yet, both the “Kerhonkson” sign and the Rhodes house were significant to the story of southern Ulster County.

There once had been an excellent reason for the Kerhonkson sign to be there. Kerhonkson and the area surrounding it had boasted fine large resorts, smaller boarding houses, clusters of cabins, and stores and shops of all description.

One of the most popular and unusual resorts was The Peg Leg Bates Country Club. Bates was the first African American to own a popular retreat in the region. His inspirational personal story, though, holds even greater significance.

Born Clayton Bates in 1907 in South Carolina, he lost a leg at the age of 12 while working in a cotton gin plant. An uncle made Clayton a wooden leg (a peg) and he ultimately became known as “Peg Leg Bates.” Always a lover of dance, his handicap did not stop him–his fame and joyful tap dancing spread around the world. Bates was featured more than 20 times on the Ed Sullivan variety show and had two command performances before the King and Queen of England.

Bates operated his country club from 1951 to 1987. Locally, a portion of Route 209 in Ulster County was named “Clayton Peg Leg Bates Memorial Highway” in his honor. He died in 1998 at 91. His obituary in The New York Times provided the following insight:

“Mr. Bates went on to become one of the most popular tap dancers in the nation, an irrepressible performer who was as much acclaimed by his fellow dancers as by his audiences. He performed from the 1920’s through 1989 in a career that included vaudeville and clubs, stage musicals, film and television.”

Signs of New Wealth

In its heyday Kerhonkson had a beautiful train station accommodating the crops of city people venturing to the out-of-doors in this “foothills of the Catskills.” Kerhonkson, though not technically in the Catskills, was considered by most to be part of the “Jewish Alps” and the “Borsht Belt,” other colorful names covering upstate New York resorts.

Times Changed

The little village of Kerhonkson withered and died like so many others that had prospered throughout the agricultural, industrial, and tourism revolutions of the mid-19th through early 20th century. The canals, railroads and paved highways had ferried building materials, produce, people, ideas, and differing cultures to and from the Ulster County’s interior and the beautiful Shawangunk Mountain range. Each of these transportation systems and the fertile and beautiful lands they traversed spelled opportunities for getting ahead in Kerhonkson.

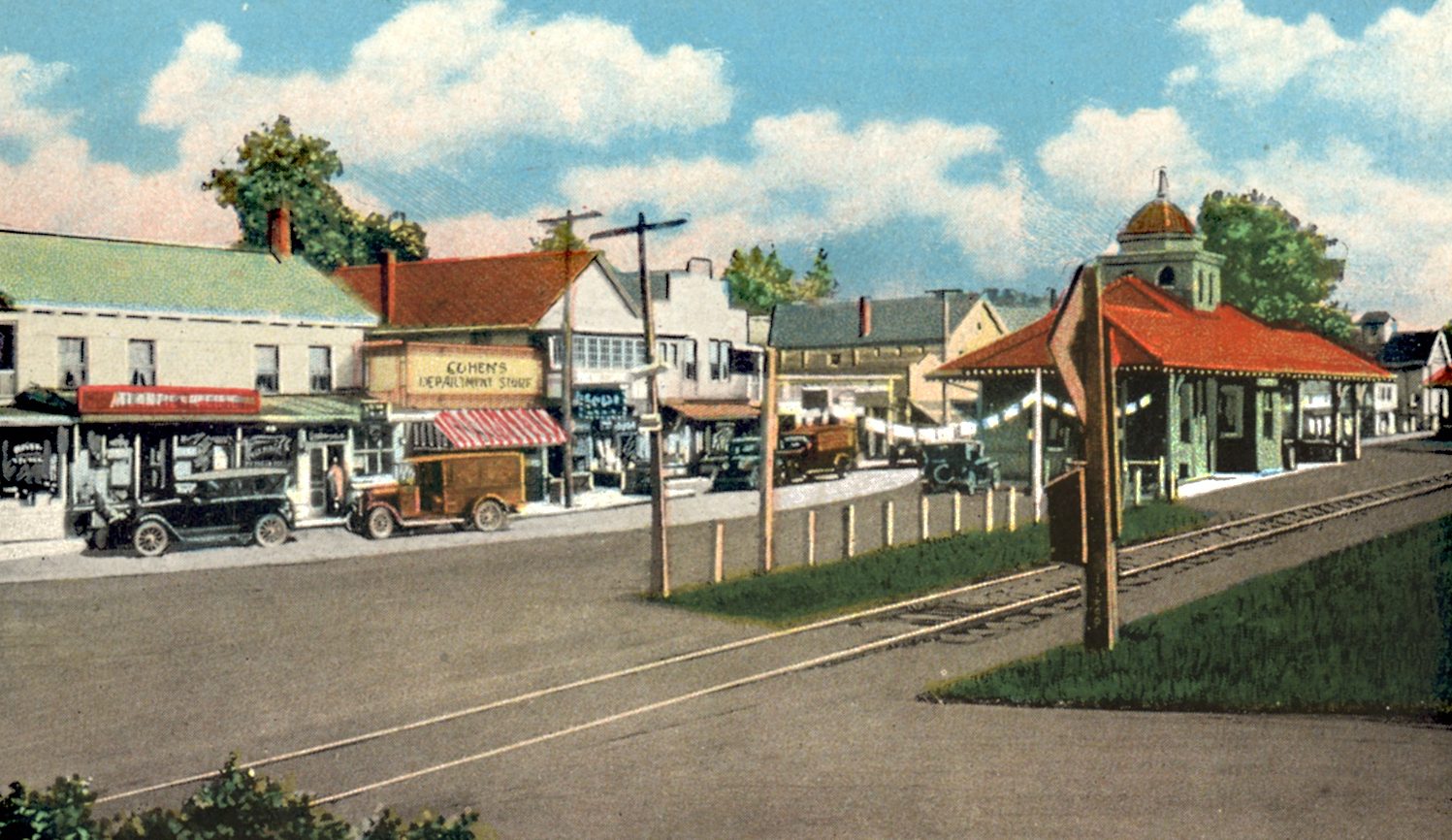

The large background photo at top was taken in 2016. It shows the same line of buildings as in the second image, a postcard from the 1920s. The 2016 photo shows no colorful awnings, no signs proclaiming “Cohen’s Depart-ment Store,” no railroad station, no cars, and most importantly, no people. Opportunity had moved on, but before it went, many fortunes were earned and much of historical interest transpired.

Circa 1920 postcard “Business section and Railroad Station, Kerhonkson, NY.”

Middleport

The formative years of Kerhonkson were shaped by the canal, hence the town’s early name, Middleport. According to the 1995 Town of Rochester’s historical resources survey prepared by Harry Hansen, “Kerhonkson (formerly Middleport) is a hamlet properly in the Town of Wawarsing. The hamlet began as a Canal era community that now straddles Route 209 and the Rondout Creek and extends slightly over the town line into Rochester.”

Hansen continues, “The railroad also had an effect on the agricultural community in Rochester. The most important aspect of this was the opening of creameries to receive, pasteurize and ship milk at the Kyserike, Accord and Kerhonkson (train) stations.” He explains that until the creameries were built there was no way to ship milk. It had to be churned into butter for sale or consumption at a later date.

The threads of economic development are always woven by those seekers of a better way, and the milk industry is a microcosm of that process. As new markets for milk expanded, dairy herds were enlarged, barns built, hay fields developed, silos constructed, and farm equipment invented or upgraded. At the turn of the 20th century, almost 90% of workers were in agriculture. By the 1960s, this was reduced to a mere 3% of the population. This wonderful confluence of bright minds and ambition fed us and freed up labor and capital to underwrite the development of manufacturing and leisure. It also freed youngsters to attend school in a less chaotic way. More families lived in villages and cities, and education no longer meant miles of travel to attend school or the disruption of schooling by farming’s demanding schedule.

The industrial revolution also put more money into the pockets and purses of the middle class allowing for scheduled vacations to places like Kerhonkson. The same trains that brought the tourists took the milk.

Today, though the bungalow colonies are gone and the big resorts struggle to become relevant again, farming still holds sway in Kerhonkson. Large road-side farm stands such as Kelder’s is yet another sign of the yearning in most of us to get back to the earth–even if only vicariously.

End of the Road

The Rhodes house that had once proudly displayed its Queen Anne gingerbread, port cochere, and stately tower and the Kerhonkson sign were gone in a blink. In reality, their disappearance was just an exclamation point at the end of a long road of decline for both.

Yet the end of any road is also its beginning if you get there and just turn around. That is where Kerhonkson finds itself today—turning around. Maybe this is the year the little shops will once again have a prosperous purpose and an awning.

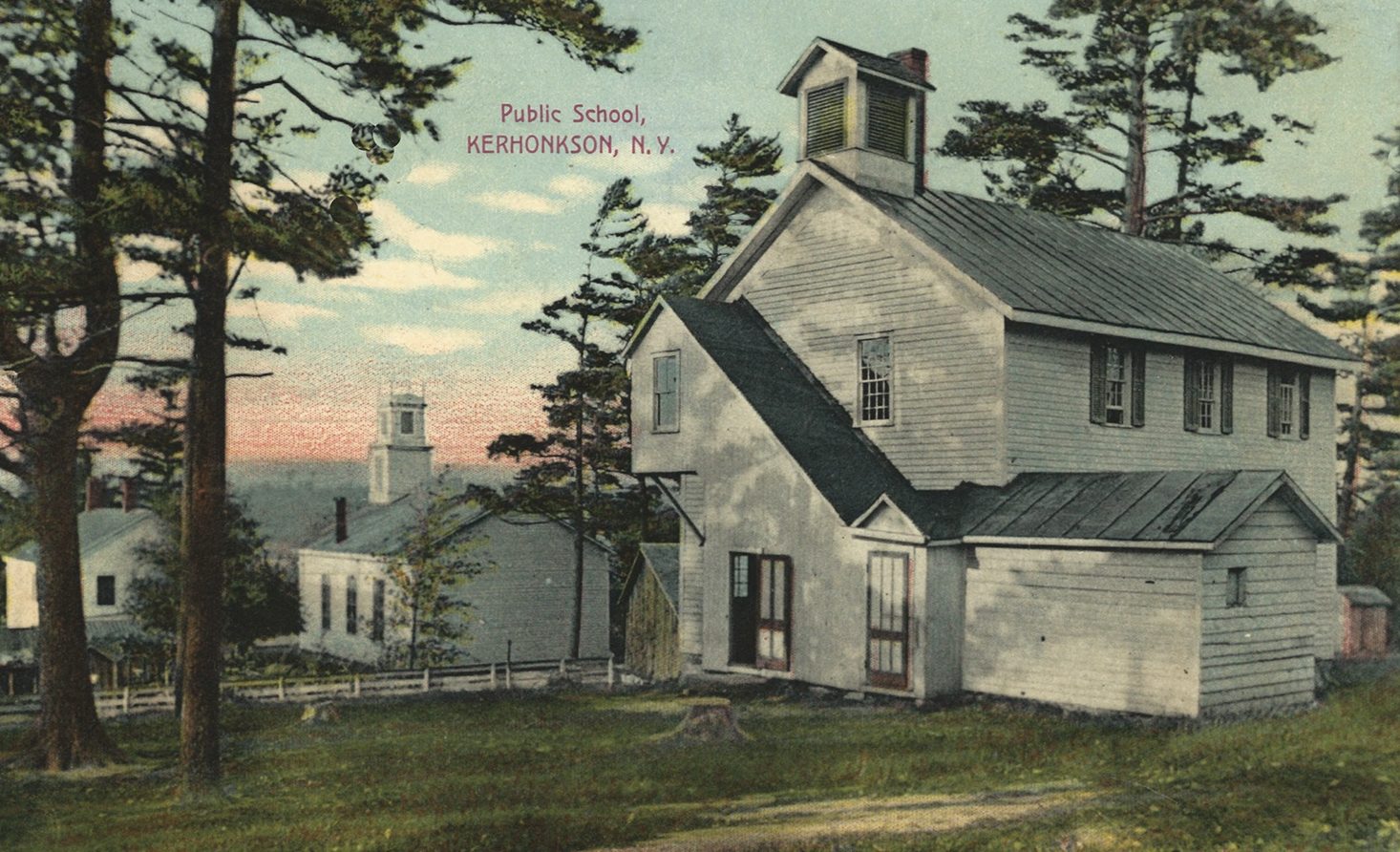

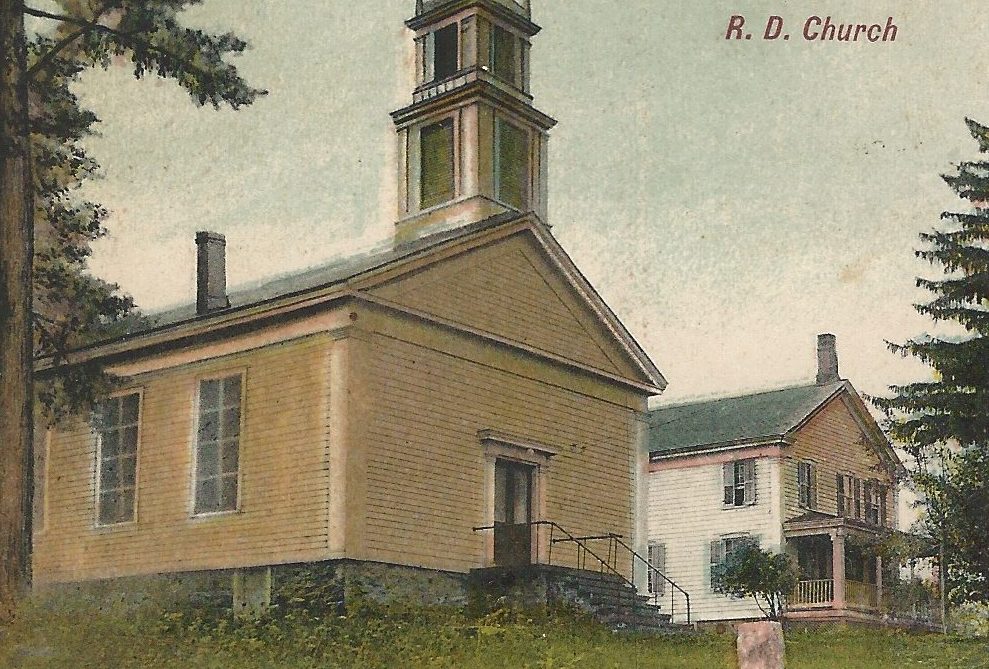

“The Public School, Kerhonkson, NY,” postcard was sent in 1908. The church in the background is the “RD (Reformed Dutch) Church”.

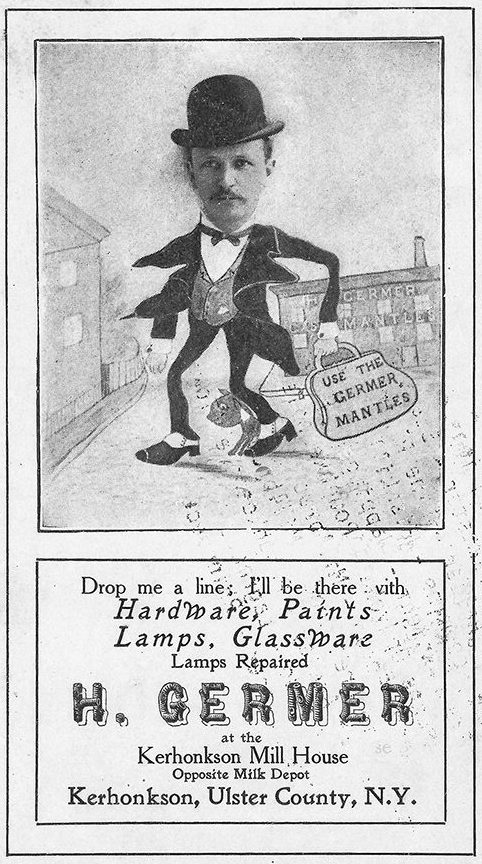

Sales piece for H. Germer at the Kerhonkson Mill House. The face is probably that of Mr. Germer.

The world’s third-largest Garden Gnome, named Chomsky, is at the Kelder Farm, Rte 209, in Kerhonkson.

RD (Reformed Dutch) Church

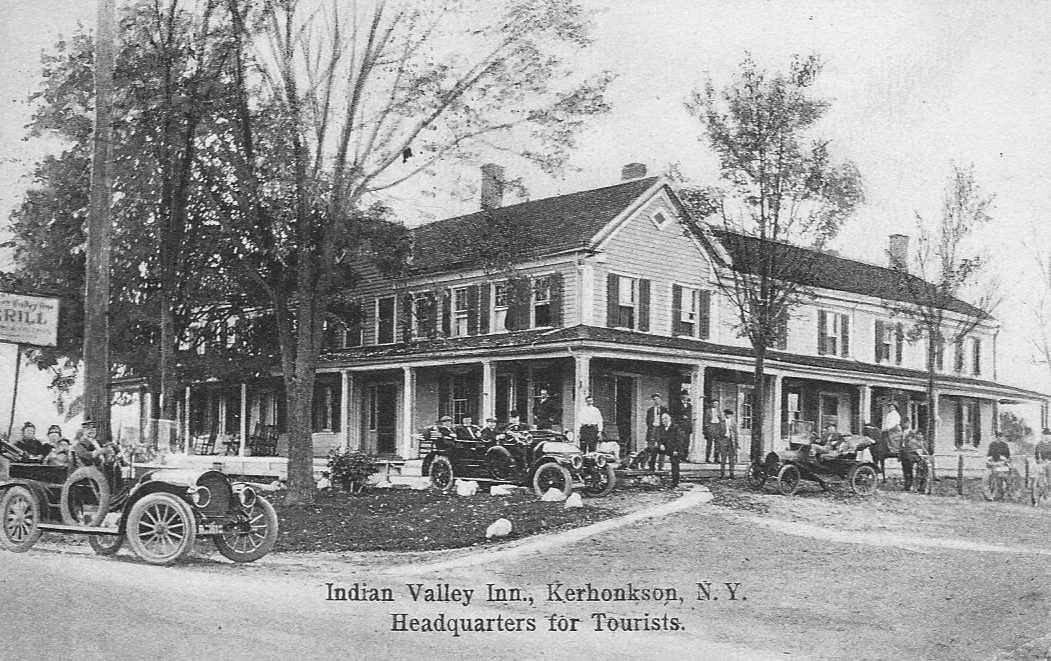

Indian Valley Inn, Kerhonkson, N.Y., Headquarters for Tourists

images from the collection of Vivian Yess Wadlin