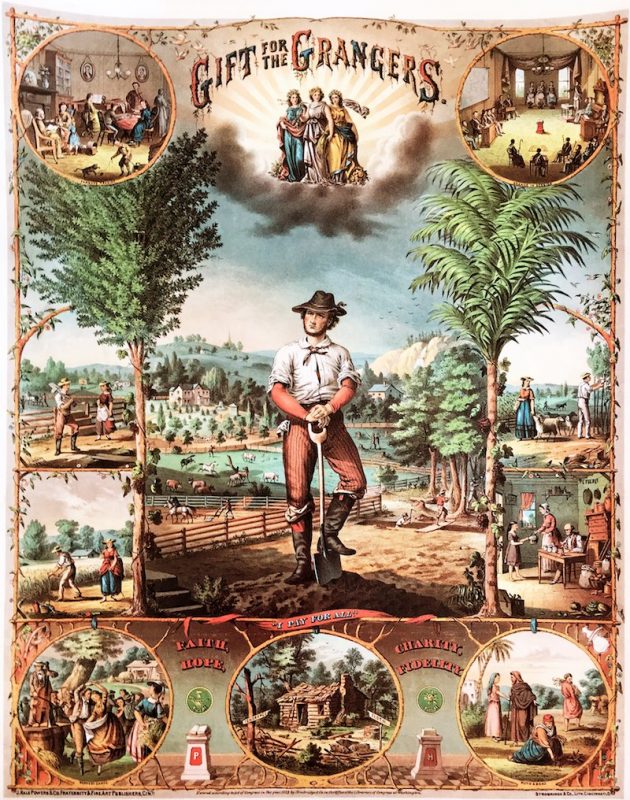

Poster given to new Grange members, 1873

Patrons of Husbandry

Spring 2019

“Its primary object is to bring about a union among the farmers of the Republic, for it is its cardinal maxim that only in union can the agricultural class show its strength and make it felt.”

“Its primary object is to bring about a union among the farmers of the Republic, for it is its cardinal maxim that only in union can the agricultural class show its strength and make it felt.”

History of the Grange Movement (Edward Winslow Martin, 1873)

1867

The United States Civil War had disrupted the nation and extinguished unnumbered American lives. And while it was over two years earlier, a war of another variety was percolating across the fruited plains. Economic plunder was to be had in the halls of Washington, DC, as railroads were granted rights-of-way, often via eminent domain. The rail lines became fiat monopolies in the transportation of goods–and those goods were most often perishable food crops.

Clintondale 1928 member booklet including names of officers for that year.

That year, Oliver Hudson Kelly founded a society of farm families to spread ideas and best practices in agriculture, and to lessen the loneliness of men and women living on widely separated farms. He called it the Patrons of Husbandry. The local-level organizations, known as Granges, quickly became the voice of voters. Farming families recognized the power they held as a group could help with the many and deepening problems they faced–especially ruinous transportation costs, lack of access to loans for modern equipment and to tide them over until the harvest, and little access to technical advances in production.

Kelly’s amazing Granges sprouted like winter wheat wherever food grew. “By 1875, barely eight years after its founding, grange halls were built in all 44 states of the union, with Grange lodges numbering about 20,000 and membership claims amounting to some 800,000,” noted E.W. Martin in his clear and detailed explanation of the organization, History of the Grange Movement or The Farmer’s War Against Monopolies, published in the mid 1870s.

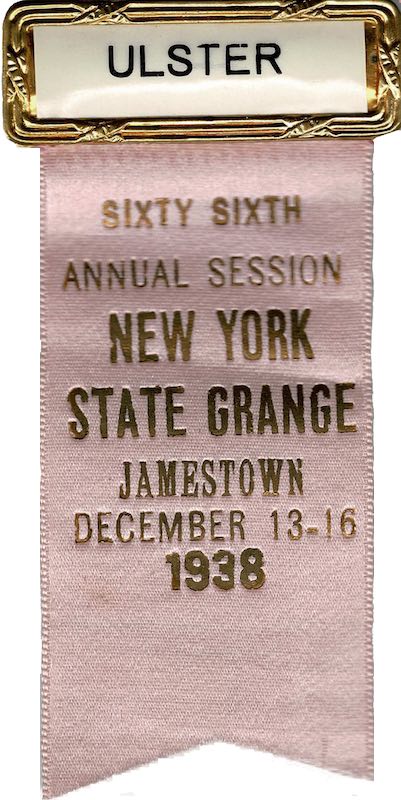

Pin for an Ulster delegate to 1938 NYS convention in Jamestown, NY.

Martin’s history makes it clear in his 534-page tome that membership was open only to actual farming families, with a special invitation to the women of farming to participate. It was not open to others involved in agriculture, such as machinery manufacturers, shippers, middlemen, or shopkeepers. The book is eloquent in laying out the plight and the cure for the economic hardships of farming and Grange membership benefits over and above of those of dollars and cents.

As with many organizations of the day, there was a strict hierarchy of order within each hall, county, state, and within the national leadership. The Patrons of Husbandry still maintain rigorous bylaws dictating all that is expected of officers and members.

The Patrons’ membership took on the railroads claiming the lines existed as an almost virtual monopoly granted by the federal government, and therefore Washington had an obligation to control the management and pricing of its creation. The farmers were successful in bringing about the “Granger Laws” in the midwest which brought some control over fees charged by railroads. The Grange political power was also felt in other areas, including the fair pricing by grain elevator companies for storage and the development of postal services to the rural areas.

Rural Free Delivery

Prior to the late 1800s, there was no home delivery of mail to most rural areas. Anyone not living in a village had to either drive to the nearest village that had a post office or to pay to have mail delivered to them. Those in favor of a United States Postal System with Rural Free Delivery (RFD) had a powerful ally in the then Postmaster General John Wanamaker. In addition to that lofty position, Wanamaker was a major retailer who recognized the unserved market for mail order that existed outside the village square, and he understood the lure of catalogs.

Enemies of RFD were varied and vocal. They included shopkeepers who feared the mail would allow shopping without the shops–similar to fears today that internet retailers will close brick and mortar stores. Additionally, RFD was resisted by fee-for-delivery businesses as RFD would routinely deliver the packages to outlying homes. Large retailers such as Sears and Roebucktm were in favor of RFD which was officially established in 1896–three years after the retail giant was founded. The ubiquitous Sears’ catalogs made many rural shopper’s dreams-come-true.

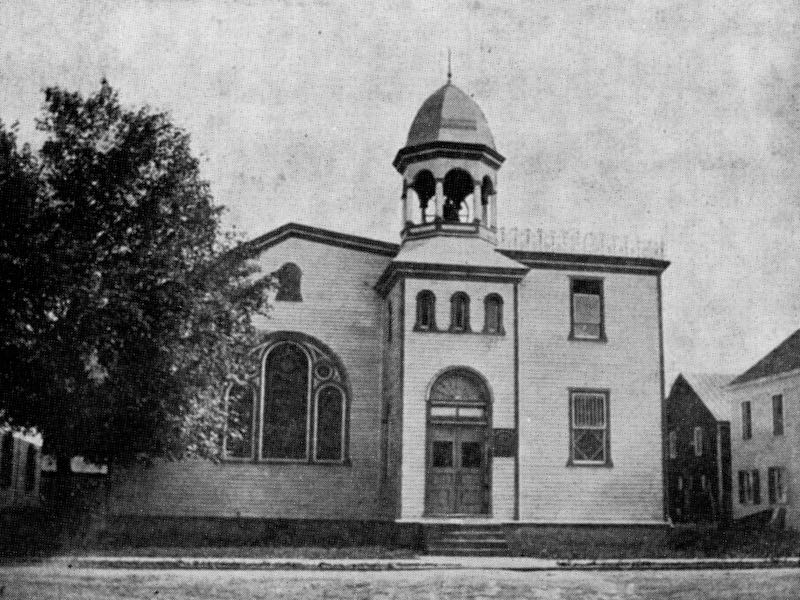

Rosendale Baptist Church that became the local Grange Hall. The building burned in 2004. Rosendale image courtesy of the Century House Museum. And thanks to Linda Tantillo of the Rosendale Library for information on Rosendale’s Grange.

Other Benefits

It may seem that the Patrons of Husbandry and their Grange-hall communities would not have taken root very deeply in Ulster County as the area did not rely on railroads to the extent of communities farther west. Ulster had good access to New York City and Albany via rivers and canals, and it had toll roads and public roads of varying quality. But Patrons of Husbandry and its Granges were more than just political organizations. The Granges could and did band together and get discounts on all manner of productive machinery from sewing machines to tractors.

Each Grange Hall had a number and a name. Each local Grange Hall was of a 4th degree in the hierarchy of the Patrons. In 1903 the Ulster Granges banded together and formed the Pomona Grange. This organization would be one step up to a 5th degree.

State level Grange organizations were the 6th degree, with national the 7th and final degree. Suggestions with a national impact funneled up to the 7th degree organization to debate and lobby for in Washington. One of the first orders to emanate from the state level was a resolution to urge its “Representative and Senator to use their voter (sic) and influence in favor of Parcel Post,” noted Mary B. Bonik, Secretary of the Ulster Pomona Grange in a report titled “History of the Ulster County Pomona Grange: 1903-1933.” Parcel post carried larger packages than RFD.

Kripplebush Grange, image courtesy of the Kripplebush Grange.

Grange Sprouts

At least three other important groups grew out of the Grange movement: The Cooperative Grange League Federation Exchange (GLF), the 4-H, and the Cooperative Extension all evolved from the concept that made the Grange strong. GLF was formed July 22, 1920, and headquartered in Ithaca, NY. GLF provided cooperatively sourced feed, seed, and equipment that served farmers for decades. Some of you may have lived in the area long enough to remember the New Paltz GLF on North Chestnut Street–now the Salvation Army store. As with most GLFs, New Paltz’s was built near a rail siding, a low-speed spur that connected to the Wallkill Valley Rail Road. Farmers arrived at the siding carrying their empty feed bags and would shovel the grain into them emptying the railroad boxcars, wrote Beth Hoad, a Palmyra, NY, historian in her article “What Happened to…G.L.F.”

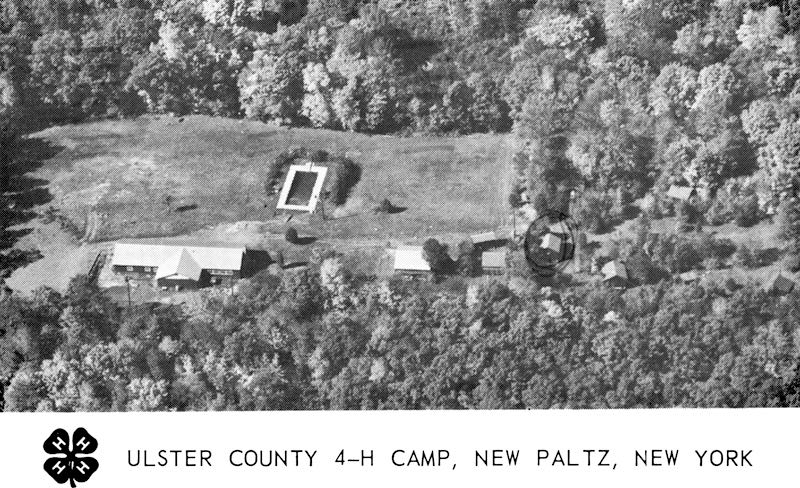

Postcard showing Ulster County 4- H Camp on Burleigh Road, off Van Nostrand Road, Town of New Paltz. Land was donated by Chet and Aggie Elliott.

The Ulster County 4-H camp was built on land donated by Chet Elliott, Sr. He and his wife, Aggie, were great supporters of the local 4-H, to which this author belonged. The camp was located on Burleigh Road in the Town of New Paltz. The official 4-H organization site explains how and why young people became involved.

“In the late 1800s, researchers discovered adults in the farming community did not readily accept new agricultural developments on university campuses but found that young people were open to new thinking and would experiment with new ideas and share their experiences with adults. In this way, rural youth programs introduced new agriculture technology to communities.”

Many families, including many Elliots, were involved in the Grange and its offspring. The Chet Elliott, Sr., farm was on Plutarch Road; three other Elliott farms were on North Ohioville Road according to Peter Elliott, great-grandnephew of Chet Elliott, Sr. Many family members still live on family farm lands, though none currently farm.

Mary Jo and Elvin Elliott are honored at the Highland Grange Hall on its 50th anniversary. Mary Jo has been a member for 70 years.

Additionally, the senior Chet was a board member of the New Paltz GLF. Chet’s daughter-in-Law, Mary Jo Alhberg Elliott, grew up in the village of New Paltz and related that although her family did not farm, the Grange Hall was where much of the social action of the village took place.

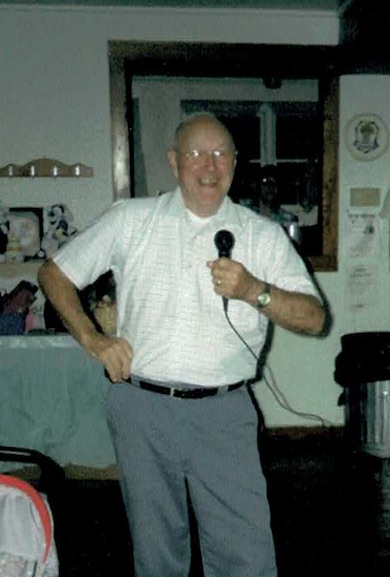

Elvin Elliott hosting a penny social at the Highland Grange. Courtesy of Mary Jo Elliott.

Local Grange attendees have said the halls were special social gathering spots for everything from penny socials to square dancing. Mary Jo Elliott and Lorraine Graziano Wheaton recall the early New Paltz Grange as one of the few places where people of all ages gathered and enjoyed each others’ company.

The New Paltz Grange Hall, called the Huguenot Grange after the French Huguenot families who established the town, stood on North Chestnut Street; its site is now a parking lot behind The Bistro and Lola’s restaurants. The photo below of the Huguenot Grange 1028, established in 1916, is from Mary Jo’s 1949 New Paltz yearbook. The Grange membership at that time was 167 and it had supported the Senior Class with a yearbook ad and photo.

Huguenot Grange. Grange was an advertiser in the 1949 yearbook of New Paltz High School. That Grange Hall was on N. Chestnut Street. Now a parking lot behind The Bistro.

As farming changed, GLFs and the Eastern States Farmers’ Exchange were incorporated in 1962 into today’s Agway, a brand currently owned by Southern States Cooperative.

The US Department of Agriculture’s website states the reason the Cooperative Extension System exists: “The pace of innovation in the agriculture-related, health, and human sciences demands that knowledge rapidly reaches the people who depend on it for their livelihoods. The Cooperative Extension System (CES), in partnership with the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, is translating research into action: bringing cutting-edge discoveries from research laboratories to those who can put knowledge into practice.”

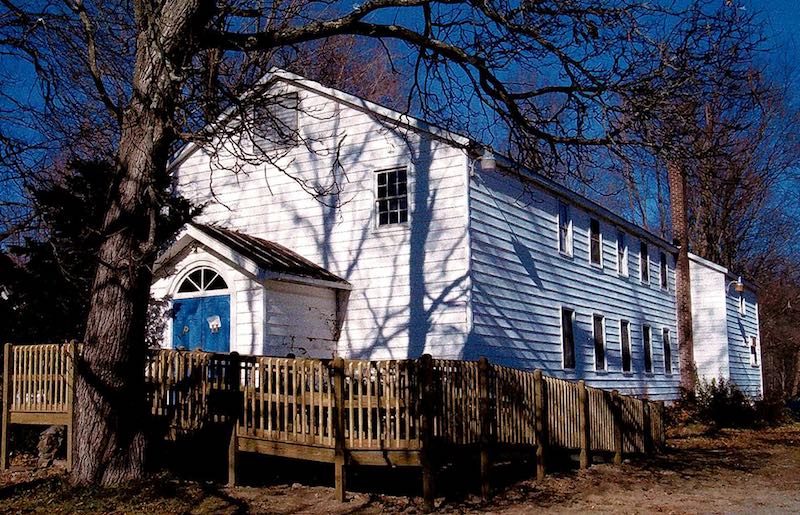

Former Patroon Grange building, Route 209, Accord, NY now owned by A&S Hardware. Image courtesy of Plattekill Historical Society. Info, thank you, Rik Rydant.

Tom Lopoint photo, Milton Grange, taken in 1991.

Highland Grange. Photo by Mary Jo Elliott showing the newly installed handicap ramp., 2005. Building constructed in 1932 for $10,000.

Recent Grange News

The Plattekill Grange is now the home of the Town of Plattekill Historical Society. It remains an active Grange Hall and is one of just two remaining in Ulster County. The Highland Grange is still active as of this writing, but may close shortly as membership has dwindled. Closing will be discussed at the state level in early March 2019. If it closes, it will end Grange activities in Ulster County. Grange bylaws require at least two active organizations. Watching the potential demise of this once vibrant organization is a painful reminder that not all change necessarily moves us ahead.

Young farmers, where are you?

North Chestnut St. Parade with the New Paltz Grange Hall in the back. Photo courtesy of the Haviland-Heidgard Historical Collection at Elting Library.

Unless otherwise noted, all images in this article are from the collection of Vivian Yess Wadlin