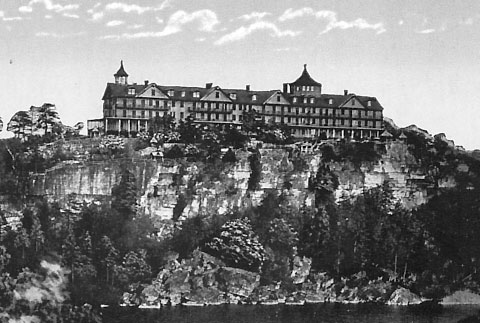

Lake Minnewaska hotels, Wildmere, opened in 1887 with an addition completed in 1910, and Cliff House hotels, built in 1879. Image is from a double-size post card.

Lake Minnewaska Mountain Houses

Summer 2009

For most of tourism’s history on the Shawangunk Ridge, the Mohonk Mountain House was one of three Smiley family-owned vacation destinations for the well-heeled. All were set above pristine, glacially- formed lakes and astride the Shawangunk white conglomerate cliffs, each hotel’s magic drawing parched thousands every year to “take the air.”

The other two hotels, the Lake Minnewaska houses, Cliff House and Wildmere, suffered the fate of many of the state’s “mountain houses” and large 19th century hotels—hard times and hot fires. This is part of their story, the memory of their last “care-taker,” Sam Lewit.

Wildmere and Cliff House had gone out of the hands of the Smiley family in 1955 when the hotels and about 10,000 acres were sold to the property’s general manager, Kenneth Phillips, Sr. The new owner had big plans to modernize the hotels’ offerings, including building a ski center (Ski Minne), and serving alcohol—a departure from the hotels’ Quaker-run first century of operation. The new owners could not stem the flow of vacationers to exotic places as air and auto travel became common. Cliff House was abandoned in 1972 and burned in January 1978. It was uninsured. Wildmere burned in 1986.

Today, the land is the Minnewaska State Park Preserve. The following personal glimpses of Minnewaska are Sam’s… and he takes the story from here…

I started working at Minnewaska originally as a dishwasher, just out of college. It wasn’t my dream job, but the “spell” of Lake Minnewaska quickly came over me. I was hooked. Imagine living on thousands of acres of rustic beauty with a crystal clear blue lake, rock cliffs, summerhouses all around, and two beautiful 200-room Victorian hotels overlooking a lake. One sat on top of a bluff and was called “Cliff House” (built in 1879 and no longer in use when I worked there). The other hotel, “The Wildmere,”(where the main parking lot is).

What was not to love about the situation in which I found myself? I was in paradise. I loved every minute of it.

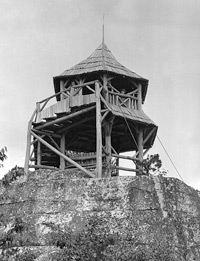

Cliff House built in 1879 in a circa 1915 postcard image. Building stood at 1800 feet elevation anchored in the Shawangunk conglomerate. Below it, a lake so blue, it was often described as lapis lazuli. Card sent June 1917, with “Minnewaska” post mark, to someone in the Dept of Agriculture, Washington, DC.

When I started working there I knew little about the financial troubles of the hotel. I’d hear stories about bits of acreage being sold to the State of NY from time to time, but I certainly had no clue that in just a few short years, both hotels, many of the structures and summerhouses would not only be totally gone, but all traces of them removed and replaced by lawns, picnic benches, and porta-potty’s.

On the cold snowy night of January 3rd, 1978, I was working in the kitchen of Wildmere, washing the dinner dishes. A bright orange sky caught my eye. I ran outside into the miserable night… it was snowing, windy, and the visibility was near zero. Without being able to actually see it, I knew Cliff House was on fire.

Everyone ran up the hill to the hotel. The owners’ son, Ken Phillips Jr., was running inside the flaming building trying to save some of the antiques. I ran inside with him and helped. We actual pulled out a Grand Piano, among other pieces of fine furniture. The fire was raging over our heads on upper floors and, when a ring of fire appeared around the light fixture above us, we bolted.

The next morning all that was left of this 100 year old majestic hotel were dozens of still-standing fireplace chimneys and tons of twisted metal frames from the beds and charred claw foot bathtubs. It was tragic. The Cliff House had not been insured, the fire protection had been turned off and people broke into the building constantly. The cause was never found, but the fire was thought to have started in a third floor room filled with mattresses.

After about a year of dishwashing and repairing the dishwasher a few times, I convinced my boss that what I really enjoyed was building maintenance. I was soon on the maintenance crew. Ken Phillips Sr., the owner, taught me well and I still tap into that foundation of knowledge today. I learned electrical, plumbing, road grading, snow-fighting, plaster repair, and, what I found most interesting, steam boiler repair.

Wildmere was originally opened in 1887, and it was the building still in use when I worked there. In 1911 Wildmere was enlarged to accommodate 350 guests. It depended on two steam boilers.

One was a mammoth piece of equipment housed in a separate building (behind and below today’s parking lot area…. there are still concrete steps going down to where it stood). The other boiler was smaller and more modern. It was in the basement of the 1911 section. The newer one never gave me any trouble, but the old one was constantly requiring TLC. I couldn’t begin to guess how many times I had to get up at 3am on a frigid morning to get that old thing fired up. Anyone who works on or operates steam boilers will tell you that they are “alive” and have distinct personalities. This one was no different. I came to know all its idiosyncrasies. One major project involved replacing a bad tube inside the boiler. This involved draining it, getting up inside it (almost 2 stories high), cutting out the bad tube and putting in a new one. When you’re done with this procedure you are covered in soot. Since there was no hot water in the main hotel because the boiler had been off, I made the mistake of taking a shower in a vacant guest room in the new section. The chambermaid for that room was so upset with me for trashing “her” bathroom that she was almost in tears and refused to clean it. I did (eventually) clean up after myself.

Another “boiler story” that sticks in my mind: If the temperature outside got below freezing, it was absolutely necessary to fire up the boilers to prevent the pipes from freezing. As you can imagine, the cost to heat a 220-room hotel must have been excessive, and given the financial problems at the time, very difficult to pay. One night it got extremely cold, and we were caught with a low fuel supply. The north end boiler had run out of fuel, so I had to take a 55 gallon drum, set it on the back of a pickup truck, go over to the main boiler room, and hand pump fuel into the barrel. The temperature was very cold and I remember ice all over the roads and parking lot. With the frigid temperature, it was like pumping molasses. It took forever just to get a few gallons into the drum. Then I drove over to the north end, pumped the fuel into the north end boiler tank and started it. I had to go back and forth, probably a dozen times to get enough fuel to keep the furnace running until our oil delivery in the morning. I was frozen! But it was a very heroic feeling “saving” the hotel.

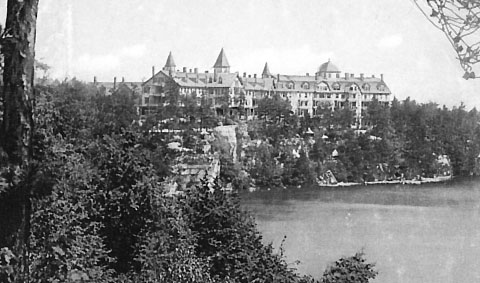

Wildmere, built in 1887 and enlarged in 1910, elevation 1710′. Image from a postcard mailed in 1942 with the “Minnewaska” postal cancellation. Its one-cent postage stamp reads “United States of America, Industry, Agriculture for Defense,” with the Statue of Lady Liberty for illustration.

One of the fondest memories of my Minnewaska days was exploring the neat places within the hotels and outbuildings. Originally, the hotel had its own post office. I went into the closed-off post office and looked at all the neat canceling equipment and cubby holes, and even metal stamp plates with the word “Minnewaska” on them. Everything was still there as if the people had just disappeared. There were numerous storage closets throughout the hotel. One closet would have cases of brand new, unused menus from the 1920’s, other closets would have boxes of 50 year-old rate cards. Probably the most fascinating were all the utility buildings. One was a wood workshop (with pulleys, lathes, and boxes of beautiful old woodworking tools), a carriage garage filled with old horse carriages and sleds, a more modern garage (still there) with old vehicles, large carriages and snow plows, and even a sawmill with everything more or less still there. It was like living in a museum.

While there was always something that needed fixing in the hotel and other structures, there wasn’t always the money to do it. On “slow” days, we hiked around the lake picking up trash, or went out in a canoe making sure there were no submerged cans or bottles in the shallower parts. The Phillips were fastidious about keeping the place pristine. I always respected their stewardship. Although we were basically in a sinking ship, we kept the brass polished to the very end.

My original living quarters were in the dormitories over the kitchen and dining room area. There was a series of rooms with a communal bathroom at the end of the hall. Nobody managed this system, so when you started working there, you just found an empty room you liked, and when you left, you took what you wanted and left the rest.

One of the many long-gone Lake Minnewaska Summerhouses. Photo from glass negative in the private collection of Sam Lewit.

These 40 or so rooms were filled with furniture and odd things from previous employees. There were more dorms down in the basement, but no one stayed there—except the raccoons.

The dorms did not have radiators but were heated by a large steam pipe going through the rooms on its way to the main parts of the hotel. This rarely heated the rooms sufficiently, so I took empty coke cans and fashioned radiator fins and attached them to the pipe to pull more heat from the pipe. I’d also set empty cans filled with water on the pipe as well to siphon off as much heat as I could from the pipe.

At some point I moved from the main hotel to a building dedicated as employee housing. It had been totally empty. I don’t remember ever asking… you just did things like that and hoped nobody would mind. My new home was located to the right of the Smiley building that still stands at the end of the parking lot. Later, I graduated to a house with other employee friends off the mountain on Lyon’s Road. This was a great house (still there). We had a wood stove for heat. However, there was no water or plumbing, so we bought a little pump and a small six-gallon water heater to wash dishes. The water came from a rainwater cistern next to the house, so it was pretty nasty, but it worked. There was an outhouse in the back, and we would shower at the hotel.

In November 1979, Minnewaska closed its doors. But work continued for me. Ken Phillips Sr. had plans to build a house for himself and his wife on the cliff. The name of the house was to be Windsong. It is the house you see now on the cliffs. I helped build the foundation by pulling giant boulders out of the ground near the sawmill which is an area not far from where the barn sits today. Ken Sr. was without a doubt the most amazing man I’d ever known when it came to building. He seemed to be capable of building anything. Before the foundation was finished, I left and moved to Accord and eventually became a machinery mechanic at a factory in Ellenville.

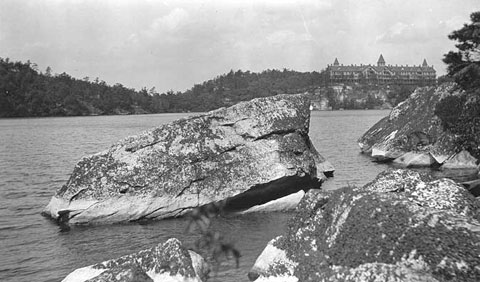

Photo, about 1906. Huge, lake-side conglomerate boulders at Lake Minnewaska and Wildmere. The hotel’s 1911 addition has not been added yet (was added to the right side of hotel as pictured). Photo from the collection of the Phillips Family.

I wasn’t there when Wildmere burned, but I did visit soon after. I then moved to California to be near my sister where I’ve been ever since. In the 1990’s, I took a trip back to visit, and could not believe what I saw. Everything was gone! All traces of the hotels, the outbuildings, the water towers… completely gone. I remember breaking down and crying when I saw that. It was disturbing to see that every last trace had been removed. When I got home, I wrote a letter to the State of NY Parks Commissioner asking if there was anything that could be done to memorialize the great amount of history that was once there. She responded that there were plans in the works for an educational facility in the future. Of course those plans never materialized. I immediately started working on a website about Lake Minnewaska.

In 2001, I was invited to stay with Ken Phillips, Jr. and his wife at Windsong. Ken’s father had passed away several months previous. Ken Phillips Sr. and his wife had a life estate on Windsong that stipulated they would be able to live there until they both passed on, at which point the house would revert to state property. Ken Jr. (who was denied a life estate) was packing up at Windsong when I arrived in fall of 2001.

Lake Minnewaska Summerhouse (gazebo) photo from a glass negative in the private collection of Sam Lewit.

It was a magical week. I enjoyed staying at Minnewaska past closing time, hiking around at night, watching the sunset from Windsong. I’ll never forget lying in bed with all the windows open. The sound of the crickets was deafening, yet incredibly soothing. This is a scenario that probably occurred for a hundred years for tens of thousands of guests at the hotels. We worked in Ken Sr’s office marveling over the many photographs of Minnewaska , the guests, the hotels, the lake, the gazebos (many are on the website, www.lakeminnewaska.org).

One day, Ken suggested we fly over the Shawangunks. We headed to the airport and hopped in his small plane. We flew over Mud Pond, Awosting, Minnewaska and Mohonk circling low and taking pictures. It was a view of the Shawangunk I had never seen and it was a picture perfect day. However, just seventy miles to the south there was a horror unfolding that would change our world: we flew on the morning of September 11th, 2001.

I know people were happy when the park system took over. I, too, am glad that Minnewaska is available to hikers, bikers and climbers, but I still feel having the hotels there was a better thing for everyone. I’ve heard people say that the Minnewaska I knew was private and inaccessible. While it was private, it was actually more accessible at that time than it is now. Anyone could pay a small day use fee (exactly like today… but cheaper) and have full access to the entire area. And there were more things to do: horseback riding, carriage rides, canoes and row boats, tennis, golf, lunch with family… these activities were available to everyone regardless of whether you were staying at the hotel or not.

And you could stay longer and enjoy Minnewaska in so many additional ways: as a guest you could watch the moon rise over the lake, have a meal in the dining room, bring older folks and share a carriage ride so they could also see the wonders of the area. Imagine taking a canoe and exploring the lake shore or going for a swim in the middle of the lake (yes, you were allowed to swim anywhere in the lake because the lifeguards were in canoes). For all of us who worked there and served guests and maintained the place, we got to enjoy all of this as well.

There were two trail systems at Minnewaska. The larger was a network of hiking trails or paths wandering through the woods and among boulders, along the cliffs and next to the streams. The second was the series of roads that were used for horseback riding and carriages. The trail system was far larger than it is today under the Park system (see the map on the website) and led to a number of interesting places. The paths were marked with red arrows and some, such as Witches’ Cave, and the path around Minnewaska were short walks that were great for kids or families. Unfortunately, although a few of these trails are still there, most of the paths have been covered with brush and tree limbs to close them. Apparently the Park System made the decision to simply obliterate these secondary trails to avoid added maintenance and access expense.

Minnewaska Summerhouses from glass negatives in the Sam Lewit Collection.

Trees in photo on right appear to be American chestnut, a tree obliterated by fungus in early 1900s.

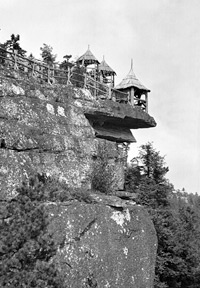

The summer houses (New England term for gazebos) were one of Minnewaska’s most visible features. I think it’s safe to say that everyone loved them. These were rustic covered benches built from American Chestnut that had mostly died off fifty or more years before I got there from a fungus epidemic. The wood was still sound and covered with carved initials and names. Each one was placed where there was a special view or setting and each was unique. Most had names: Stepping Stone (located at the far end of the lake and protruded out onto the lake), Agnew’s View, Sunset View, The Double Decker, Coronation Rock, Near Top, Beacon Hill, Kempton Ledge were some of the names I remember. Some were simple benches, some were round with circular benches, and at least one was two stories tall! They were great for just absorbing the surrounding nature in solitude, or curling up and reading a book on a rainy day. Sadly, all have been removed except for one that’s been rebuilt of modern materials.

As I write this from California, I often think about my years at Minnewaska… as some of the best times of my life.

— Sam Lewit

Sam now lives in Berkeley, California. His website is www.lakeminnewaska.org.

Unless otherwise noted, postcards are from the collection of Vivian Yess Wadlin.