The Rise and Fall of Cedar Glen

Ruins in Reese Preserve—The last remains of a sad family

Fall 2008

The newest park in the Town of Lloyd, the Franny Reese Preserve, provides spectacular views of the Hudson River and Poughkeepsie.

But it also contains a mystery. Go a bit further along the trails, and you will come across castle-like ruins and the remains of several other stone structures. Something important must have been here a long time ago, but what was it? And what happened to it?

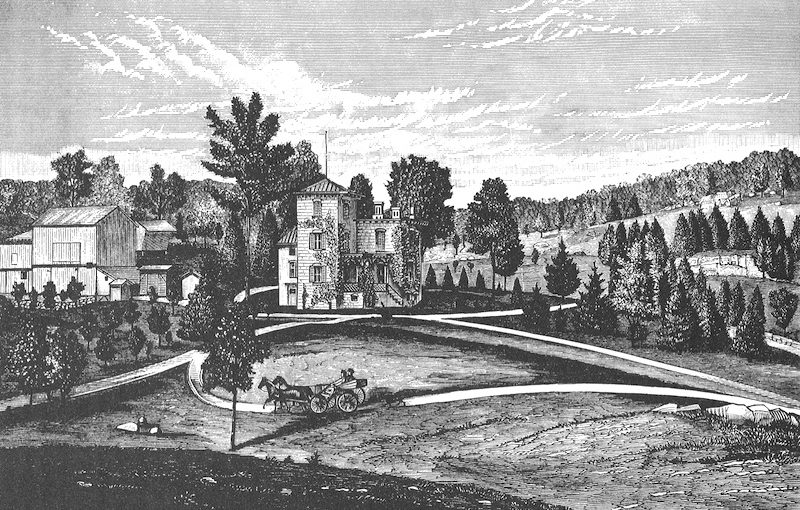

To find the answers to these questions, we must trace the property’s title back to the period when the structures were built. The style and construction materials date the buildings to the middle of the 19th century, when the property was owned by a Charles H. Roberts of Poughkeepsie. Over a period of several years, Roberts transformed the primeval hillside into Cedar Glen, one of the finest Hudson River estates of the day.

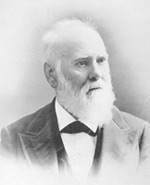

But life had not always been easy for Roberts. Born in rural Saratoga County in 1821, two of his ancestors had served in the War for Independence. His great-grandfather was offered a commission as an officer in the king’s service, which he refused, and he died in battle when he was struck by a cannonball. His grandfather, who was a captain in the same regiment, continued to fight until independence had been secured. He was commissioned a major in the Continental Army by George Washington, and was inducted into Washington’s Society of the Cincinnati.

Such patriotic service did not guarantee a secure future for the Roberts family. As the son of a poor farmer, Charles Roberts spent his childhood years working in the fields from dawn to dusk. He had little opportunity for schooling until he left home at the age of 18, and then he had to support his education by hiring himself out as a farmhand. While attending the private Glens Falls Academy, Roberts became acquainted with a local doctor who tutored him in the practice of medicine. Roberts decided to continue his medical education, and obtained a scholarship at the Albany Medical College since he could not afford the tuition of less than $100 for the first term.

After he obtained his diploma and was qualified to practice medicine, Roberts decided that he did not want to compete with the snake-oil dealers and quack doctors of that era, and turned to the practice of dentistry. He located his dental practice in the bustling city of Poughkeepsie, where he would have a better chance of earning enough money to pay off a note that he had signed to cover his second term’s tuition at Albany Medical College.

A Pioneer in Painless

Seeing a dentist in those days could be a very painful experience, since the few anesthetics that were available did not always work. Having studied chemistry in college, Roberts decided to apply his knowledge of that subject to the practice of dentistry. By using a solution containing tannic acid, morphine and a tiny amount of arsenic, he was able to relieve the pain of dental work by killing the nerve endings in a patient’s mouth. As word of Roberts’ “painless dentistry” spread, his dental practice burgeoned. He continued the practice of dentistry for 19 years, and made several other innovations in the practice which spread his fame throughout the state.

Seeing a dentist in those days could be a very painful experience, since the few anesthetics that were available did not always work. Having studied chemistry in college, Roberts decided to apply his knowledge of that subject to the practice of dentistry. By using a solution containing tannic acid, morphine and a tiny amount of arsenic, he was able to relieve the pain of dental work by killing the nerve endings in a patient’s mouth. As word of Roberts’ “painless dentistry” spread, his dental practice burgeoned. He continued the practice of dentistry for 19 years, and made several other innovations in the practice which spread his fame throughout the state.

While he was continuing to practice dentistry, Roberts became interested in several business pursuits. One of his first ventures outside of treating patients was to manufacture preparations for use by other dentists. He then used some of his dental profits to buy Western lands and railroad stocks.

In 1866, he married Catharine Freeman of Poughkeepsie, and two years later he decided to retire from dentistry at age 47. Although he intended to pursue “horticulture and agriculture” at his estate on the west bank of the Hudson River, his next career as a successful businessman was about to begin. He acquired controlling interests in several New York paper mills, and stock in dozens of railroads, pouring the profits that he earned into building up his Cedar Glen estate, named after cedars that grew on the property.

Dr. and Mrs. Roberts had six children. Probably the most notable of them was his second daughter, Grace Roberts, who operated Ulsterdorp Farms near the present Bridgeview Plaza for many years. In 1897, Dr. Roberts bought the farm property for Grace, but never deeded it to her. It included Reuben Deyo’s 1819 inn on the Post Road (Route 9W), which New York State later demolished to construct a new approach to the Mid-Hudson Bridge.

As Dr. Roberts advanced in years, legal struggles began among his children. In 1901, his oldest daughter, Frances, brought a suit in the New York State Supreme Court at Albany to have him declared incompetent and to have a committee appointed to manage his property. Always regarded as a bit eccentric, the 80-year-old Dr. Roberts proved himself to be very competent by traveling to Albany alone and submitting 18 affidavits from prominent physicians and businessmen, all of whom attested to his competence.

Strife Over Inheritance

The lawsuit was promptly dismissed, but it foreshadowed what would happen after Dr. Roberts’ death on Feb. 11, 1909, when he left an estate valued at more than $1,200,000 (equivalent to about $152,400,000 with inflation to 2007 dollars). Legal wrangling ensued that would tie up the Surrogate’s Court for five years.

In a will that he made in 1906, Dr. Roberts referred bitterly to the 1901 incompetency hearing, and he set up trusts for his children instead of giving inheritances to them, made bequests to other relatives throughout the country, and established scholarships for poor farmer boys to attend Cornell University. Two weeks before his death, Dr. Roberts revoked that will and made a new will under which he left an undivided equal interest in his estate to his wife and six children.

The executors under the first will contested the new will, and said that the children had used undue influence to have Dr. Roberts make the second will. The second will was held to be valid, but Frances Roberts did not agree with the way that the executor was handling matters and charged him with malfeasance when he did not pay the estate taxes on time. Whenever the executor sent papers to the court, Frances filed dozens of objections. When some of her objections were overruled, she promptly appealed to the State Supreme Court in Albany. Lawyers who worked on the case had to sue to get paid. Papers on the Roberts estate overflowed from the filing cabinets at the Surrogate’s Court in Kingston, and had to be stored in boxes.

Sibling Against Sibling

Back at Cedar Glen, where Frances and some of her brothers lived, it wasn’t long before lawsuits arose over such matters as brother Irving’s ejection of Frances’ coachman from the estate. Irving stated in court that since Frances had only one horse, she didn’t need two coachmen. While waiting to receive their inheritances, the heirs had to borrow money from banks in order to pay their bills, and maintenance of the estate lapsed.

In 1913, the executor finally distributed all of Dr. Roberts’ stocks, bonds, and other personal property to the respective heirs, but nobody could agree on how to deal with the real estate. Then Frances brought suit against the other heirs and the executor, which forced a public auction of the real estate that was held on June 6, 1914. To no surprise, Frances was the high bidder on the main parcel, and acquired Cedar Glen for $17,745 (equivalent to about $2,225,000 with inflation to 2007 dollars). A smaller parcel was bid in by James J. Mack, after whom Mack’s Lane is named, for $3,020. As part of the settlement, Grace Roberts received title to her dairy farm for $1.00.

Frances retained the Cedar Glen property until her death in 1946, but after her inheritance was exhausted, she lacked adequate means to maintain it. The mansion and other buildings on the property fell further and further into disrepair.

Decline and Fall

Grace Roberts was named as administratrix of Frances’ estate, but Grace was having her own difficulties down at the farm. Rising costs and taxes had turned the once-profitable dairy into a losing operation, and Grace was also going blind. Nothing was done to fix leaking roofs and cracking walls at Cedar Glen, and the buildings were left to deteriorate into ruins. When Grace died in 1958, she had not settled her sister’s estate. Neither sister had ever married, and Grace bequeathed her farm to her friend, Elizabeth Collier.

The Cedar Glen property was left abandoned until 1969, when the matter of Frances’ unadministered estate again came before the Surrogate’s Court, and a new administrator was appointed to settle it. The property was sold to Joseph Alfano in 1971 for $85,000. By that time, all that remained of the magnificent mansion and outbuildings were crumbling walls and piles of rubble.

Scenic Hudson purchased the property from the Alfano family in 2003, and dedicated it to the memory of Frances “Franny” Reese, a founder of Scenic Hudson. In 2006, Scenic Hudson sold the property to New York State, but continues to work with the State to develop the park, and has secured grants to improve the site for public access.

The ruins of Cedar Glen provide a stark reminder of how fragile culture is, how transient success is, and how quickly nature can undo man’s attempts at civilization.

— Ethan P. Jackman, Lloyd Town Historian

The story of the demolition of the Grace Roberts Home and Barns to accommodate the Mid Hudson Bridge approach will be the subject of a future story in About Town.