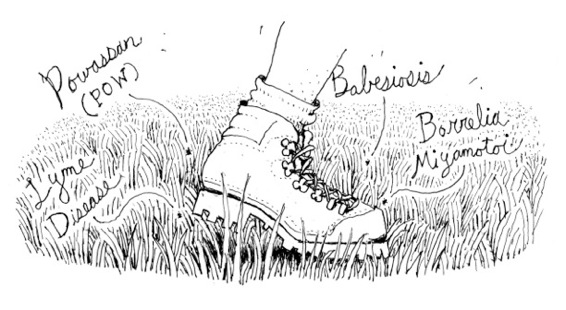

credit Daniel Baxter

A Walk in the Grass Can Change Your Life Forever

Spring 2014

Has the threat from tick-borne disease escalated so much that we can no longer take a leisurely walk in the grass? Do we need to be afraid? Or just careful? Should we tell our children they cannot play baseball or run in the park anymore? We already had enough to worry about with Lyme disease. Now, new tickborne viruses that have emerged in the Hudson Valley force us to consider these difficult questions. The new viruses include Powassan virus, Borrelia miyamotoi, and babesiosis. All are transmitted through deer ticks, (also called blacklegged ticks or Ixodes scapularis).

Perhaps the most alarming of the newly-emergent diseases is Powassan. POW or POWV is a virus related to some mosquito-borne viruses, including West Nile. It is named after Powassan, Ontario, where its earliest origins were discovered in 1958. There are several types of POW including: Scapularis (transmitted by deer tick); Ixodes cookei, (transmitted by a related tick species that usually feeds on woodchucks or other medium sized mammals instead of humans); and Powassan encephalitis. Some of these viruses may be fatal.

POW causes debilitating symptoms similar to Lyme disease, but is significantly more dangerous. Infection starts within 15 minutes of contact between human and tick, whereas Lyme can take up to 24 hours to be transmitted and therefore can be prevented. Currently there is no treatment or cure for POW; doctors can only address the symptoms. More than 50 cases of POW were reported in the United States over the past ten years and in New York 30% of those afflicted have died. Most cases have occurred during late spring, early summer, and mid-fall, when ticks are most active.

Symptoms of POW can include: fever, headache, vomiting, weakness, confusion, loss of coordination, speech difficulties, memory loss, seizures, encephalitis (inflammation of the brain), meningitis (inflammation of the membranes that surround the brain and spinal cord). However, many people who become infected do not develop symptoms.

Luckily, the other two diseases mentioned can be treated once identified. Borrelia miyamotoi, an illness that mimics Lyme disease and is its cousin, is initially very difficult to diagnose. Unlike the pathogens of Lyme disease, those of Borrelia get transmitted from the infected female ticks to their eggs. Symptoms can include fever, headaches, nausea, and muscle pain, but not the bull’s eye rash that typically develops with Lyme and makes the disease easier to spot. If left untreated, Borrelia may bring on recurring fever. People with compromised immune systems may exhibit confusion and other dementia-like behavior. Borrelia miyamotoi responds to the same antibiotic treatment as Lyme. The Mayo Clinic advises that all patients in the United States who have been infected with this virus have recovered with the use of antibiotics.

Babesiosis, the other virus on the rise in the Hudson Valley, is a rare infectious malaria-like disease. The illness occurs primarily in animals; however, in rare cases humans may contract it. Many different types of Babesia parasites have been found in animals, but only several in humans. The most common is Babesia microti, which usually infects white-footed mice and other small mammals. Infected people might not realize they have been bitten because Babesiosis is usually transmitted by ticks at their nymph stage, when they are usually the size of a poppy seed. The disease is most prominent during the months of July and August.

Human babesiosis infection may cause fever, tiredness, chills/sweating, headache, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, and muscle aches (myalgia). Symptoms can develop anywhere from a week to several months and can be mild (or even nonexistent) in healthy people. The infection may prove fatal for babies, the elderly, and those who have an impaired immune system if it is severe and untreated. No vaccine is available, but people respond well to the treatment of a combination of two types of anti-parasite drugs.

The best way to prevent all tick-transmitted viruses is to avoid getting bitten in the first place. This means you should stay away from wooded and bushy places with high grass. If you have to venture out in such areas, or even your own backyard, wear socks tucked into your pants; apply insect repellents containing DEET to exposed skin; treat clothing and gear with permethrin insecticide. Once indoors again, conduct a full-body tick check and remove ticks immediately before they have a chance to bite and attach; shower (preferably within 2 hours after being outdoors). Parents should thoroughly tick-check children, including their hair, clothing, and gear. Pets that go outdoors should also be tick-checked and immediately brought to a veterinarian if a tick is found.

The three essentials for tick survival in any given environment are warm temperatures, high humidity, and an abundance of potential hosts. Constant temperatures of less than 10° Fahrenheit will kill off most ticks, but the blacklegged tick thrives in the winter months. According to the National Reference Laboratory for Tickborne Diseases, rising global temperatures and increased rainfall are contributing to the acceleration of a tick’s life cycle.

An increase in wildlife is the major contributor to the growth of tick populations, with the white-tailed deer being the biggest culprit. Ironically, factors that benefit the environment, such as is the reduction in mass spraying of insecticides and the preservation of open space, also tend to increase the tick count.

Proposals for legislation for the funding of research for the eradication of tick-borne diseases have proliferated in recent years. In the face of the growing public health concern in the Hudson Valley about the chronic and dire consequences of these diseases, it is clear that more research is crucial.