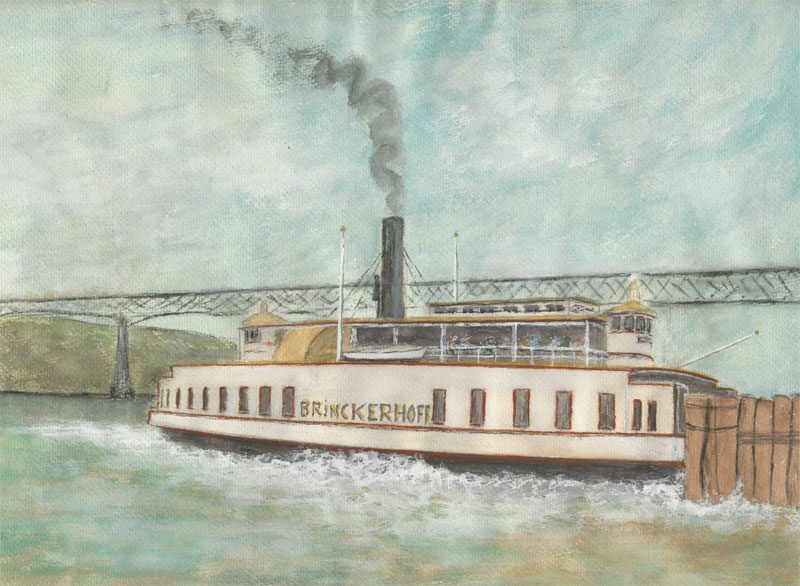

Built-1899-Newburgh, 42 years between Highland-Po'keepsie Final Trip Dec. 1941, Resting Place Mystic Conn. H. J. Meuser 1960

Painting above by Henry Meuser of Highland. He was a prolific painter of local images. Painted in 1960, this image portrays the Brinckerhoff coming into dock at Poughkeepsie. The Poughkeepsie Highland Railroad Bridge, now Walkway Over The Hudson, is pictured with the hills of Highland, green and looming, behind it. Image use courtesy of the Highland Cemetery.

A Ferry Tale

Summer 2019

Midnight, New Years’ Eve, 1941. Its light shining into the darkness of the Hudson River, the Brinckerhoff Ferry left its berth in Highland making one last crossing. Its forty-year Hudson River history sealed. Its future uncertain.

Prior to the American War for Independence, crossing the Hudson River between Yelverton’s Landing (today Highland) and Poughkeepsie meant having your own craft or hailing someone else’s. It could be a hit and miss process as no one ran a regularly scheduled boat. Then, in 1777, Anthony Yelverton added a flatboat ferry to his business empire on the west shore at the confluence of the Hudson River and Twaalfskill Creek. Yelverton’s home, pictured below, still stands. Its historic marker reads, “Yelverton House. 1754 historic site on the state and national registers. Sawmill, brick yard and store. Slaves sculled his ferry across the Hudson.” The ferry ran until 1786. Esquire Yelverton died in 1792.

Yelverton House

The late Glendon Moffett’s 1994 book on the subject of our local ferries, To Poughkeepsie and Back, The Story of the Poughkeepsie-Highland Ferry gives a comprehensive look at former boats owned by the Poughkeepsie Highland Ferry Company.

Over time, the west shore landing on the Hudson changed names often depending on who owned the land. Yelverton’s Landing 1777, Valentine Baker’s Landing 1786, New Paltz Landing 1798. According to the NYS Historic Marker at the landing today, it was the “town’s shipping center for a century and a half.”

After the human-powered craft of Yelverton came a horse-powered ferry, The Intercourse. For about five years another ferry operated between Ulster and Dutchess counties. Noah Elting operated a cable ferry from 1793 to 1798. It was unique in that it was a sailing vessel and operated as needed. Moffett explained, “If you were on the opposite side of the river from the ferry, you had to raise a white flag to signal your desire to cross. Then depending on many factors, such as weather and time of day, the ferry would usually come for you.” The Elting ferry began a regularly advertised schedule in 1798.

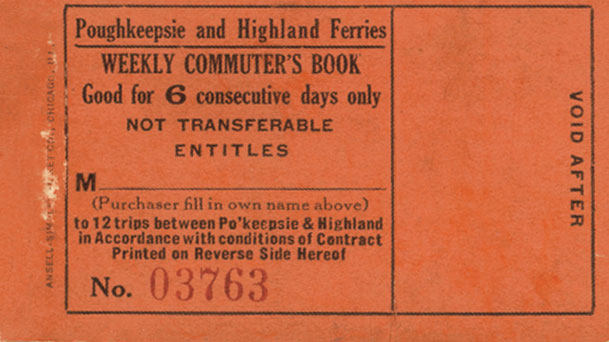

Poughkeepsie-Highland ferry weekly ticket booklet, from the collection of Vivian Yess Wadlin

Other ferries using mechanical power came and went: The Dutchess and Ulster (1834-1856), the James Reynolds (1847-1851), the J.C. Dougherty (1861-1899), the J.H. Brinckerhoff (1889-1898), The Governor Winthrop (1921-1941), The Poughkeepsie (1922-1941 when sold to the US Navy), and the Brinckerhoff (1889-1941). Most of these ferries were built in New York State–Albany, Athens, Poughkeepsie, Brooklyn, with only the Governor Winthrop “foreign made” in Connecticut. Sometimes an engine would be made by a company other than the company constructing the superstructure of the ship.

The J.C. Dougherty could carry 300-400 riders. It required new berths to accommodate its 88-foot length and 40-foot width. This ferry’s size may have signaled the bud of tourism as people would take the ferry just to enjoy the cool river breezes. Also, the huge Hudson River Psychiatric Hospital in Poughkeepsie was an important employer for people on both sides of the Hudson. Other manufacturing companies were springing up in Poughkeepsie and luring workers from Ulster County. Road building and improvements made Ulster County’s agricultural output easier to bring to the main Hudson River port at Highland. Spacious ferries, such as the Dougherty, could accommodate large wagons of that produce. With its 16 crossings per 24-hours, the Dougherty was also capable of keeping the channel free of ice in many winters. She did have to go in for repairs to due to ice damage to her paddlewheel at least once.

Each new ferry reflected the leapfrogging technology of shipping and the creative destruction of progress. As the wealth of the area grew, larger and larger cargoes and vehicles had to be accommodated. Referring to Moffett’s detailed list of each boats’ size and capacities reflects these changes. The Joseph P. Dougherty had 170 horsepower, the Brinckerhoff at 111-feet in length had 300 horsepower.

Postcard Image of the Brinckerhoff ferry docking at the Poughkeepsie. 1930

The Poughkeepsie-Highland Ferry Company owned the last ferry to cross–the Brinckerhoff. She was a sidewheel walking-beam affair, and in 1941, the last of the company’s vessels still in service. Their other two ferries, the Poughkeepsie and the Governor Winthrop, had ceased operation.

On August 5, 1930, to much fanfare and celebration, the ribbon was cut on the new Mid Hudson Bridge. Pedestrians and motor vehicles were suddenly freed from the tyranny of scheduled ferry runs and the vagaries of weather.

The Poughkeepsie-Highland Ferry Company held on for just over ten years after the Mid-Hudson Bridge opened. It slowly drew off the traffic that had kept the ferries financially afloat.

When the “car bridge,” as it was called, opened, its fares were many and varied for cars of different wheelbases. For instance, under 100-inch wheelbase was $.80. Over 100 inches– $1.00. Those fares were in each direction. The most expensive crossing was for heavier trucks starting at $1.50 and increasing by $.50 for an additional five tons. No load allowed over ten tons. Motorcycles were $.25, with sidecar $.35. It must have been a nightmare to collect tolls that first year–in addition to these tolls, there were separate prices for wagons of differing length, number of horses, or horses not pulling a load, but being led across the span. Oh, and bicycles, buses, and trailers of different weights had their own fee schedules. Looking at the changing tolls over time for the bridge, you can estimate what years saw the end of horses and wagons, motorcycle sidecars, and cars of vastly different wheelbases.

To compete, the Poughkeepsie Highland Ferry company tried lowering fares, but one by one the ferries were sold off. The City of Bridgeport, CT, purchased the last ferry, the Brinckerhoff, and from 1942 to 1950 it was the Pleasure Beach Shuttle. Bridgeport then gave the Brinckerhoff to Mystic Seaport in Mystic, CT.

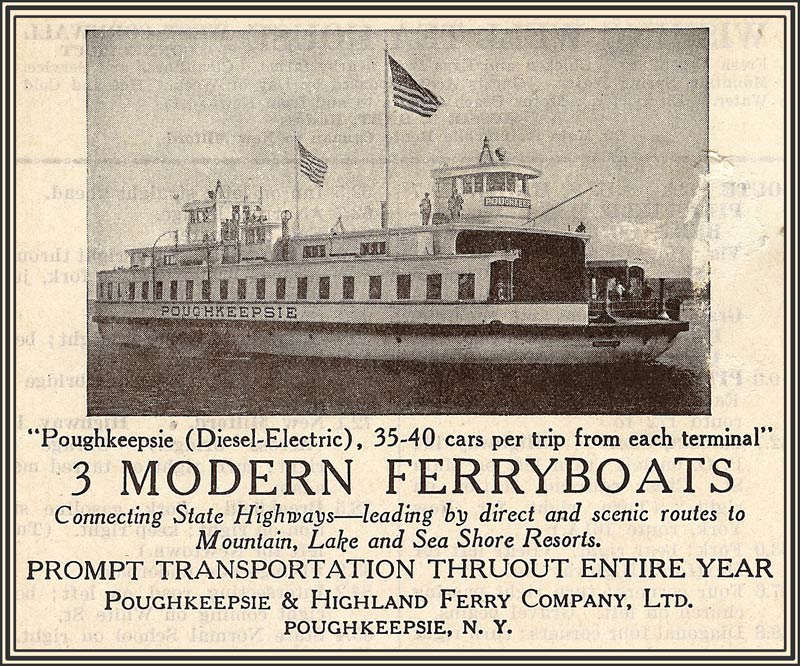

Ad from the Poughkeepsie Eagle News, circa 1930

It was hoped that the Steamship Historical Society which had taken an early interest in the Brinckerhoff, could raise the $60,000 it would take to rehabilitate the ferry. At the society’s meeting in 1960, members decided on a different tack. They would run her aground, demolish the ship’s superstructure and preserve its unique Fletcher walking-beam engine-the last if its ilk to have been in service.

According to Bryan Lucier, Membership and Public Outreach for the Steamship Historical Society of America in Warwick, RI, (www.sshsa.org),

“The ferry was donated to Mystic and was an exhibit there until around 1961. After that, she was sold to a man in Pawtucket, Conn., who was “going to make a marina of her.” However, before that could happen, she burned while lying on a riverbank. Her whistle was removed and preserved before she left Mystic, and in 2014 the whistle was donated to the Steamship Authority to be used on the ferry Nantucket.”

The new Nantucket was indeed outfitted with that whistle. Should you ever ride the Nantucket, make sure you listen for the echos of the Poughkeepsie–Highland Ferry Company’s Brinckerhoff.