Charity Begins… at the Mary and John Arbuckle Farm

Summer 2010

A New York Times’ article of 1903 tells of a $12,000 purchase by John Arbuckle of 282 acres of farm land in New Paltz, NY. According to the late Peter Harp’s Horse and Buggy Days, the first purchase by Arbuckle was of the Deyo Farm, and shortly after he purchased the Helena Smedes’ and six other farms. As the leading importer of Cuban sugar and coffee in the United States, John Arbuckle had the resources to purchase all the land in New Paltz. His property eventually covered more than 1200 acres here. This was, however, a farm with a mission over and above a restful place for the Arbuckles to vacation, and more than a farm to feed the growing population of New York. John Arbuckle and his wife, Mary Alice Kerr Arbuckle, whom he married in Pittsburgh, PA in 1868, planned a cool respite for the working men and women, and the children of the stifling hot cities. It would become a working, self-supporting vacation for those who needed employment in the “open air” and would allow them to withstand the “wear and tear of city life.” Again, according to Harp, the Arbuckles planned to “…establish at New Paltz a practical charity designed to help humanity to help itself.” The Arbuckles planned a building 210’x 65′ with a glassed-in veranda that would accommodate both work and play. Work inside would follow what many altruistic organizations of the time had as an aim: To allow men and women to develop productive skills by producing/building useful and decorative items in the “hand-crafted” mode. Elbert Hubbard was an earlier thinker along those lines and Eleanor Roosevelt’s Val Kil was a later version of that tradition.

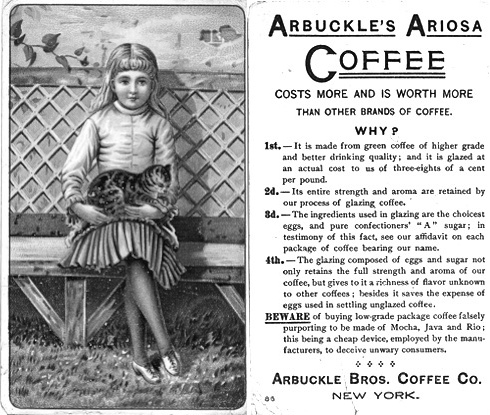

This is an early advertising card for coffee imported by the Arbuckle empire. Arbuckle was at one time the largest importer of coffee and Cuban sugar in the US.

Arbuckle even offered a $100 award for ideas on how to make such a project the most rewarding for the people who would reside there for a working “vacation.” The land had a golf course, lawn tennis courts, and Wallkill River access for fishing and boating (boats provided by the Arbuckles).

From Harp, “The keynote of the colony was ‘work.’ Everyone is better physically and mentally who earn their own living, was Mr. Arbuckle’s theory because they are made to feel they are of some use in the world.” Arbuckle constructed an industrial home for handicapped workers and built the Colony Building…” (287′ long x 80′ wide and four stories tall). Just as construction was almost complete, it burned.

Twice a month, Arbuckle had forty under privileged children brought to New Paltz for two week’s vacation complete with fresh air, fresh food, and exercise.

One of his legacies for us today is the road west of the Wallkill. “Arbuckle improved the road crossing the flats because it was dirt, often muddy, and difficult to traverse. Harp explained, “He (Arbuckle) donated $5,000 to the Town and supplied a truck all summer working on this road. Many hundreds of tons of stone wall was used in the foundation.”

Arbuckle’s claim to fame and fortune came at the end of the Civil War. After running a grocery concern with his older brother, Charles, Arbuckle commercially roasted and packaged coffee for the retail market. This was rather a novel idea as coffee, for the most part, was sold green and roasted by the purchaser at home. That process was hit or miss for a consistently good cup of joe. Not only did Arbuckle invent and patent the better roasting machine, he broke new ground (no pun) in packaging and marketing. Additionally, he and his firm took on the “sugar trust” and began importing and refining sugar in the US.

So the next time you cross the flats and stop at Wallkill View Farm Market for cup of coffee, you can thank John Arbuckle twice:—the smooth road and the smooth coffee.

On his 1912 death in Brooklyn, The Arbuckle estate was estimated to be $33,000,000 — at a time when a dollar was relatively valuable, and tied to gold so the politicians could not simply print and inflate the money supply. Since income tax was not picking pockets until 1913, it was also somewhat easier to amass real wealth.

Arbuckle had attended public schools in PA with others who became notable entrepreneurs and philanthropists, including Henry Phelps (coke and steel), and Andrew Carnegie (whose steel supports our Walkway over the Hudson, and whose own philanthropy built many public libraries).

* * *

Information for this article is from Peter Harp’s Horse and Buggy Days; All About Coffee by William H. Ukers; and Clayton A. Coppin’s article at www.FEE.org: John Arbuckle: Entrepreneur, Trust Buster, Humanitarian. Thanks to Carole Johnson at the Haviland Hiedgerd Historical Collection at the Elting Library for confirming the correct size of the building that burned: 287′. Mr. Harp’s article has a typo saying the building was 900′ long.

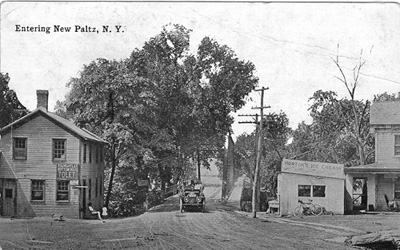

The Wallkill River bridge at the west end of Main Street, New Paltz, as you would have seen it going to visit the Arbuckle farm, the Minnewaska, or Mohonk hotels about 1909.