Dashville on the Wallkill

Spring 2006

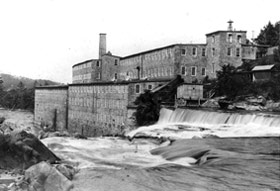

A Dimick factory at Dashville taking power from the Wallkill (circa 1865).

The north flowing Wallkill River passes through towns in New Jersey and New York before joining its larger sister, the Hudson, via the Rondout Creek near Kingston. Along its bed, the Wallkill enriches the soils and scenery of the towns of Wallkill, Gardiner, New Paltz, Rosendale and Esopus, among others. Enrichment in return was not always the case, as many towns treated the Wallkill as a convenient sewer, sweeping the towns’ effluent out of sight, out of mind.

The Wallkill’s many personalities include the slow flowing sediment-rich waters that flood and nourish, rapids rushing around and over rocks, and ice floes blocking highways, crumbling buildings and carrying off bridges. The Wallkill is powerful.

In the Town of Esopus, the Dashville hydroelectric station, Central Hudson’s generating plant and dam built in the 1920s, was not the first to harness the Wallkill’s untiring might. The falls at Dashville (Route 213 east of Route 32 in Esopus) have seen more than 16 mills and factories producing everything from lumber, flour and knives, to cotton and wool products. More than a thousand workers were supported during the early 1800s by these and the industries serving them. The circa 1836 Perrine’s Burr Arch covered bridge stands as testament to the area’s economic importance. The NYS legislature authorized the Ulster County supervisors to raise the funds to build it. Two toll bridges were also privately constructed and are pictured elsewhere in this article.

Billhead from invoice dated Dec 21, 1892.

The huge J.W. Dimmick complex (company billhead spells name Dimick, in other documents, it’s Dimmick) pictured here made wool blankets for the Union during the Civil War. Later, they made carpets that covered the floors of many American homes, hotels, and businesses.

Curved stone bridge abutment from twin bridge on Route 213 side of Wallkill.

Jean and Rosener Wheeler (Rosener was born and raised in Esopus) took me on a tour of the Dashville area. Along the way he pointed out locations of long-gone mills, supply buildings, bridges, and roads. He indicated the foundation of a wool storage building and another where the butcher shop had sold it wares. He pointed out the sites of the two iron bridges whose stone abutments are still very evident, and quite lovely, just off Route 213. Using these bridges to cross the Wallkill you would have taken the first bridge to an island, traveled a short road along the spine of the island and then taken the second span from the island to the other shore.

At this juncture of the area’s history, I turned to a source of information as steady as the Wallkill itself: Horse and Buggy Days, by the late Peter H. Harp. Mr. Harp wrote a short piece titled Rifton, here repeated in its entirety with permission from the Harp family.

“Dashville is wholly within the original New Paltz Patent and Rifton Glen is at the boundary line between the New Paltz and Kingston Patents.

These two natural waterfalls were of great importance to the early settlers. In the early part of the last centure (sic)(1800), there were no conveniences such as electricity and stationary steam engines, The people were dependent upon natural water power to operate their saw and grist mills, and factories. The falls at Rifton were known as Buttermilk Falls.

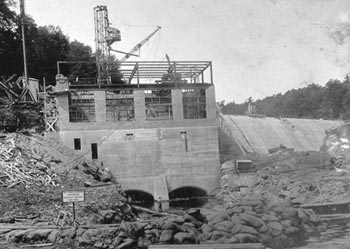

1920 photo of hydroelectric dam construction at Dashville

At first I was not very much enthused in writing about Rifton until I remembered my mother saying that her grandfather, James Tamney, worked there in his youth. So I looked it up in the Biographical Records published in 1896 and on page 755 found that he was born July 6, 1809, in Scotland and migrated to American and worked as a foreman in the Cotton Factory at Rifton.

B. & J. Arnold built the factory. Rifton was originally named in their honor and called Arnoldton.

In June 1860, a Scotchman by the name of Jeremiah W. Dimmick purchased the factories which were having financial difficulties.

Jean and Rosener Wheeler flank the dedication monument at Perrine’s Bridge in February 2006.

During the Civil War of 1861-1865, he made blankets for the Union Army. Business prospered during the following years and Mr. Dimmick erected his wonderful house just east of Perrine’s Bridge over-looking Dashville Falls and called it “Wood Crest.”

The factories made carpet that had a nationwide reputation. I can remember going with my folks to these carpet mills to purchase carpet.

My father was a harness maker and he made several sets of fine harness for Mr. Dimmick.

About 1909 the unions came into the mills and demanded more money and less work. The result was no work or pay. Mr. Dimick left to vist (sic) his native Scotland and not a wheel has turned since that time in the factories, most of which have been dismantled. Many of the strikers moved to St. Louis.

There was also a powder mill near the junction of the Wallkill and Rondout Rivers, operated by James Howe who sold the firm to Smith and Rand. The powder mill blew up several time. When there was an unusual, unknown disturbance, I recall the old folks saying, “Sounds like the powder mill has blown up again”.

Lord fill my mouth with worthwhile stuff,

And nudge me when I’ve had enough.”

January 19, 1966, Peter Harp

***

From Town of Esopus Story, we learn the earliest mills at Dashville Falls were established in about 1800 and used to spin cotton into yarn. “The housewife took it home and wove it into cloth on a handloom.” At about the time of the Civil War, the mills were manufacturing “…better cloth than could be made at home,” and so women were relieved of at least one tedious chore.

Dashville was named for the son of Mr. Butler, the owner of the original cotton mill. At the time of the 1979 writing ofTown of Esopus Story, Dash Butler’s tombstone still stood “…in the burying ground at the back of the church.” We could not locate it.

Today, the largest structure at Dashville is the Central Hudson dam. Earlier, around 1916, the Town of Esopus had granted the electric franchise to Central Hudson and they built the Dashville plant, and subsequently the Sturgeon Pool hydroelectric station was completed (1924). With the construction of the two stations, the power of electricity flowed from the Wallkill to the whole township and outlying areas.

Electricity is now generated primarily at Danskammer Point and Roseton, both along the Hudson River. They are not powered by the river’s flow, but rather get their energy from fossil fuel fired steam generators.

Early 1900 postcard showing the twin bridges and island.