Delight of the Humble Bee

Spring 2010

Previous articles on the stresses affecting our common feral (wild) and domestic honeybee populations discussed the disappearance of entire colonies. The term, Colony Collapse Disorder, sums up a focus of current bee research that has important implications for local agriculture.

Although farmers in the Hudson Valley rent hives of pollinators for the apple crop, there are still feral colonies making a home here. Two years ago a swarm colonized behind our home’s cedar siding—right next to our entry door, of course.

For the past two seasons, anyone entering or leaving our house runs the ‘”bee gauntlet.” The girls (foraging bees are female) on occasion have bumped into me, but so far none have felt threatened enough to sting. Watching them enter and exit their hive is mesmerizing. For me, however, the most amazing part of any swarm is the process of choosing its new home. When the colony comes to the decision it is time to divide, they prepare a new queen by feeding “the chosen one” only royal jelly. She then begins to evolve into the current colony’s single source of its future—60,000 to 80,000 new bees. When the new queen is ready to take over, the old queen takes her leave. Approximately half the colony goes with her. They swarm (fly as a group) and find a safe place, some distance from the original colony, to camp out while their new home is “chosen.”

Scout bees are sent out to look for a good new colony location. These are not just any girl scouts. These are the most experienced foragers of the hive who have the most complete knowledge of the area. Many scouts go out. Each comes back with a location in “mind.” Each scout “tells” the other scouts about her find via a dance. Depending on how convincing she is and the quality of her discovery, other scouts will go to the suggested location, come back and “vote” again by a dance. When all the scouts are satisfied that one location is most accommodating, the swarm then moves from it’s holding location en mass, and voila, the new colony is home.

In the very early 1900s, men who were bee hunters would catch a foraging honey bee, put her in a cigar box with flour, jiggle it around a bit until the bee was white and let her go. She was easy to follow. The bee hunters would then “smoke” the colony and take their honey. Many forest fires were accidently set by bee hunters using smokers to keep the bees at bay while harvesting the honey.

Learn more from bee keeping classes: www.HoneybeeLives.org. Email HoneybeeLives@Yahoo.com or call 845-255-6113.

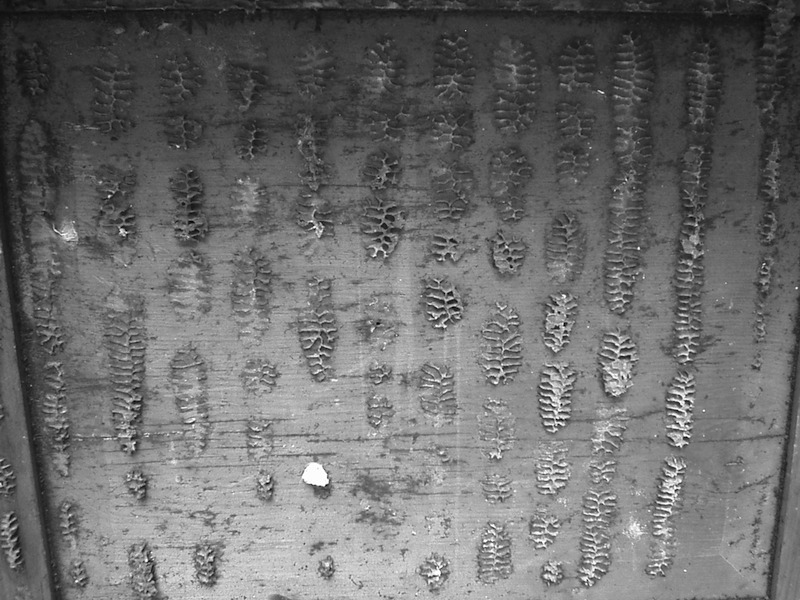

Another honey bee colony lived in the wall of the house I grew up in at 112 Swartekill Road, Town of Esopus (are they following me?). That colony was removed in about 1950 because the bees started finding their way inside the house. We kept much of the honey and combs. Sixty years later when we removed the siding of that house, the bits of honey comb (pictured above) were still there and looked much as they had the day the bees and honey combs were removed. We left the comb traces in place for some future generation to rediscover.

— VYW