Early Cragsmoor: The Beginning of an Art Colony

Summer 2007

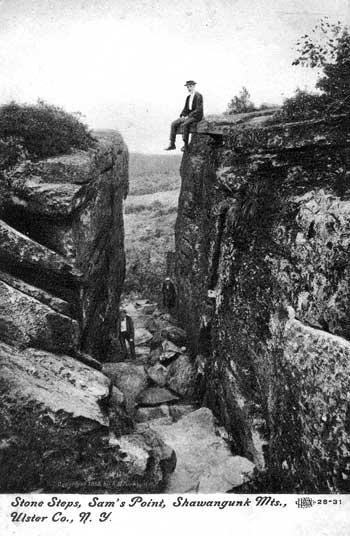

Perched high on the Shawangunk Ridge in southern Ulster County, New York, Cragsmoor has long been a destination for seekers of beauty. They have been attracted by the rocky outcroppings, jagged cliffs, sheer waterfalls, and unique vegetation, and enticed by the spectacular views of the Catskill Mountains, and the Rondout, Wallkill and Hudson Valleys. The first to pursue the heights of the Shawangunks were the Lenape, who found it an abundant resource for hunting and gathering. They sought safety in its rock shelters and undoubtedly sensed its spiritual energy. They were followed by the early settlers in the late seventeenth century, who hunted and trapped on the land. Eventually, these settlers built their own homes and survived by a combination of charcoal burning, hoop making, tanning and farming, which resulted in clearing much of the land by the late nineteenth century. The hamlet of a few homes and small farms nestled on a narrow plateau several miles long. First known as Manceville and later as Evansville, it was bounded by Sam’s Point to the northeast and Bear Hill to the southwest.

As early as the 1870’s, a new group of seekers began to discover the beauty of the Ridge. With the opening of Delaware and Hudson Canal in 1829 and the arrival of the New York and Oswego Midland Railroad branch in 1871, transportation was provided for products into and out of the Rondout Valley, and the region also became more accessible to visitors. Similar developments in transportation throughout the East gave rise to the growth of industry and expansion of cities, often with negative impacts. “As the superb natural beauty of the American landscape fell prey to the ravages of industrialization, Americans developed a craving for the artistic representation of the pristine state of the landscape” (Buff 3). Artists began to seek out locations where nature could provide inspiring subject matter for their paintings. “The grimy cities provided a market for the work of the very painters who wanted to escape from them during the hot summer months” (Buff 1056). The artists of the Hudson River School were the first to venture forth into the wild, untamed regions of the Catskills, Adirondacks, and upper sections of the Hudson Valley. Often they traveled alone or with one or two companions on painting excursions. Sometimes they camped or rented rooms in boarding houses or small hotels that were cropping up along transportation routes. A few built their own country retreats outside of the cities.

“Before 1880 artists summered at scattered points in the Hudson Valley, but in the 1880’s they began to cluster in colonies…” (Rhodes 90). and Cragsmoor is one, if not the earliest, example of this movement. It drew established artists who, although they had their own individual styles of painting and interest in subject matter, were united by an abiding love of nature and a need to work in a setting that inspired their vision and nourished their talents. This they found in Cragsmoor. It was not necessarily the wild untamed landscape depicted by many of the artists of the Hudson River School such as Cole, Church and Bierstadt who preceded them earlier in the century. After all, Thomas Botsford had already created the first tourist attraction at Sam’s Point in 1858 when he built an observatory on the summit (Botsford), to which parties were hauled in ox-drawn carts. The Cragsmoor artists sought a more gentle interpretation of nature that would provide an appropriate setting for delicately clad damsels in white organza, carefully positioned on the cliffs, or farmers going about their daily tasks.

It all began when Edward Lamson Henry, a successful genre painter and member of the National Academy of Design, and his wife, Frances Livingston Wells, also an artist, made a sketching trip to “The Mountain” in 1879. They boarded with the Mances and later at the Bleakley farm. They returned in the summer of 1881 and stayed with the Otises In Ellenville. The artist and explorer, Frederick S. Dellenbaugh, who eventually married the actress Harriet Roger Otis, also accompanied them (McCausland 37). In that same year, another associate of the Henry’s, the illustrator Eliza Pratt Greatorex, noted for her etchings of early Manhattan houses and gardens, bought an eighteenth-century farm house where she cultivated an old-fashioned garden (Hill 50). She acquired it from William Whelpley and called it Chetolah, (Cragsmoor Jouma/163), meaning “peace.” In 1883, the Henry’s purchased their own land from Hattie Keir and designed and built their home in the Queen Anne style, incorporating antique elements from older homes which were being razed in New York City. Another friend of the Henrys’, the wealthy Newport widow, Eliza Hartshorn, who also had relatives in Ellenville, arrived in 1886 for a visit and immediately bought acreage from Alex Terwilliger on the precipice overlooking the village (Cragsmoor Journal 156). The Dellenbaughs followed in 1893 with the completion of their home, Endridge, design and built by F.S. in the shingle style using natural stone and cedar shingles on the upper story and roof. Working together, Dellenbaugh and Hartshorn laid out many of the roads and building lots in this area, “selling them with deed restrictions to maintain the country atmosphere and expansive views” (Stedner1). Working together, with Dellenbaugh as the architect, they built some of Cragsmoor’s most outstanding residences and public buildings including in 1896, The Chapel of the Holy Name (The Stone Church.) It was Dellenbaugh who, in 1892, petitioned the government for a post office to serve the community and proposed the name Cragsmoor,” which he deduced from the moor-like character of the plateau, and the crags at Bear Cliff and Sam’s Point (Cragsmoor Journal 160).

And so the colony grew. the landscape painter, George Inness Jr. and his wife purchased Chetolah from Eliza Greatorex’s daughters in 1900 and began to develop the largest estate on “The Mountain” with a forty-two room mansion and formal gardens. Another landscapist, Edward Gay, built his home in 1905. Dellenbaugh invited the American impressionist, Charles Courtney Curran and his wife Grace, in 1904 (Benton), and their home, Winahdin, was built in 1910. In the same year, Curran’s associate, Helen Turner, another impressionist, built her cottage, and the illustrator, Arthur I. Keller and his wife, settled into their new house. “The selection of the site and the associated view were critical elements of many Cragsmoor homes. Today, the open vistas offered by the Ellenville watershed and the Bear Hill Preserve capture and reinforce the original intent of the builders”…Artists had come to the mountain for inspiration and it was often found just beyond their porch or front door” (Hansen 12).

The summer community was growing in leaps and bounds despite the fact that it was not easily accessible. From Ellenville, it was a slow two-hour climb in horse-drawn carriage up the steep road to the top of the mountain. Furnishings and other belongings were either shipped up the Hudson on barges or transported by train and then hauled to the mountain in ox-drawn carts from Newburg or Ellenville. The inconvenience, however, did not prevent artists from bringing all manner of objects, even as large as grand pianos. In this way, the artists and other creative minds in the community surrounded themselves with all that was necessary to create a haven of culture in the midst of what still appeared to many city folk as “the wilderness.”

Their goal was to create a cultural, spiritual, and artistic community. To this end they took it upon themselves to support a library, a playhouse, and three churches. The Cragsmoor Journal (1903-1916) records weekly calendars filled with chamber music concerts, poetry readings, plays, dramatic readings, and exhibitions, drawing upon the talents of resident writers, actors, and musicians. countless social events, including masked balls and afternoon teas, are described. The Cragsmoor Inn, built and operated by the noted portrait and floral painter, Austa Densmore Sturdevant, was the center of much of this activity and eventually boasted its own golf course.

Much time and effort was exerted on the beautiful gardens, which surrounded each home and became the focal point or background in many paintings. “Gardening was a serious pastime among the summer residents of Cragsmoor. No doubt this activity arose out of the necessity to produce fresh vegetables for their tables. Charles Curran was an aid gardener, and so was Dellenbaugh. There was serious horticultural rivalry among Dellenbaugh, Browning, and Turner. They were all noted for their beautiful flower gardens and the gardens of helen Turner in particular were know for some of the rarer types of Flora” (Benton 5). The important Arts an Crafts magazine, Palette and Bench edited by Grace Curran, occasionally featured articles by her husband on painting gardens where he often placed his female subjects (Hill 132). Some models had even more intimate connections with the gardens, serving, as did Keller’s, as gardeners when not posing for paintings. As a passionate gardener, helen Turner even domesticated native plants.” …She painted radiant pictures of women in gardens and on porches surrounded by flowers, in a very individual coloristic manner with paint almost gritty and laid on thickly and dryly.” (Gerdts 230)

With the arrival of the artists on “The Mountain,” its beauty began to intensify. The naturally spectacular scenery was complemented by gracious homes and lush gardens. But this was just the beginning of its continuous history as an active art colony. Now, more than a century later, Cragsmoor is listed on the National ‘Register of Historic Places and continues to attract artists and other residents who place great value on the importance of community and of protecting the environment. In her paper “Cragsmoor: Its Spirit and Its people,” Joan Schweighart observed, “Perhaps when the spirit of a place is strong enough it attracts a certain class of people, a people bent on preservation of the place they have been attracted to… The people who came to Cragsmoor, it seems, had as much regard and respect for each other as they did for the place itself.” This is especially evident today as they work together to preserve the historic character of the hamlet, protect open space on the Shawangunk Ridge, and nourish the talents of all who thrive in this naturally inspiring setting.

This article was originally printed in The Timeline, Ellenville Public Library and Museum, Summer 2002)

Sam’s Point Postcard. Post marked Saugerties, NY, Feb 17, 1909. From the collection of Vivian Yess Wadlin

A Breezy Day. Charles C. Curran NA, a Cragsmoor, NY artist. Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

From a postcard reproduction of the painting, The Wooing of Ann Hathaway by Arthur I. Keller, Cragsmoor, NY artist.

Bear Hill, Cragsmoor, NY