Harvesting Memory

Fall 2013

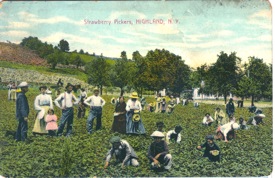

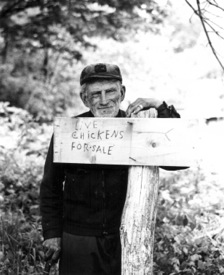

Strawberry Pickers, Highland Ulster’s harvest has changed dramatically in the past 70 years. Growing up on what had been my grandparents’ farm at the intersection of the towns of Esopus, New Paltz, and Lloyd, we were surrounded by dairy, poultry, and fruit farms. In the 1940s my father turned away from farming to work as a heavy equipment mechanic, the work he truly loved—solving the mysteries of malfunctions. Fortunately for our gustatory delight, others loved farming. In addition to my own memories, this story draws on interviews with Joseph Indelicato of Highland and Jackson Hayward Baldwin of Marlborough, both of whom spent decades feeding their families, their neighbors, and thousands of unknown others here and abroad. In addition, postcards illustrate some other important aspects of farming, such as transportation and early tourism.  Postcard of Oscar Tschirky’s Farm, New Paltz My grandfather did occasional work for Oscar Tschirky (1866-1950) whose farm is depicted here in a post card from 1904. The Tschirky farm is now the Culinarians’ Home, a retirement community for fifteen lucky people (www.culinarianshome.org). The site is just off Route 32 north of New Paltz and still comprises a huge expanse of land, lovely gardens, lakes, and really good food. Oscar was the world renown maître d’hôtel at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel and Restaurant in New York City. He is probably better know as “Oscar of the Waldorf,” and for his Waldorf Salad, among other dishes. The water shown at the top of the postcard is the Wallkill River from which Oscar diverted a stream to make the two front “lakes.” Oscar and his family (wife, two sons, and a daughter) tamed the 1000 acres, building first a “shack” and then a Swiss-style home. Eventually, the family built the complex of structures pictured. “I went for chickens in a big way—I preferred White Leghorns—had incubators for 2,000 eggs, but found that with all the labor and feed involved this was not profitable,” Tschirky said in his biography, Oscar of The Waldorf. Second home owning is not as new as we might believe—the Tschirky family initially did much of this work on weekends. Mrs. Tschirky canned, the children planted and harvested, and Oscar designed, cleared land, and later, directed hired help. Their first home, the Swiss Chalet, is visible from Route 32 north of New Paltz at the intersection with Tschirky Road. That house was recently renovated. The main building is just northwest of that house on the same road. After my father became a mechanic, a neighbor’s dairy herd pastured in our fallow fields. Neighbors cut and baled our hay for their animals. So, although it was not our farm when I was growing up, it was farmed. Its 100 acres had been purchased on July 21st, 1921 by my grandparents, Alous Jesch and his wife Mary Zidar. Their name was Americanized to “Yess” at Ellis Island in early 1900. The Yesses, immigrants to America from Austria, had lived first in Brooklyn, then Ohio, and finally here, in Ulster County. The home they purchased had been built around 1790 by the Auchmoody family and the Auchmoody burying ground is not far from the house. The house was “improved” with an addition around 1830. When the Yesses acquired it, it had no electric, no indoor plumbing, no telephone. The water source was a well house near the front door. Their school was a one room affair about a mile or so away. The road was dirt. The land was rocky, but adequate for a few cows, chickens, and almost perfect for grapes. My grandfather had a vineyard and was known for skill in grape and fruit tree grafting. One piece of his handiwork was still bearing apples of several varieties until its demise sometime in the 1970s. The family raised and butchered their own animals, grew and canned their fruits and vegetables. They made wine. They took in summer boarders, cut firewood all year, helped cut ice in winter for large hotels, including Mohonk, and harvested yellow poplar trees to sell to the basket factory in Highland. My grandmother would walk to the New Paltz -Highland road at Eltings Corners, take the trolley to Highland and pick up hand sewing work to do when there was nothing more pressing to occupy her. A word about ice harvesting: According to the Mohonk Bulletin, Volume 90, 2000-2001. “At Mohonk, the lake was a convenient ice pond; starting in 1870, two to four thousand tons of ice was harvested from the lake each winter.” Many ice companies thrived locally in the pre-refrigeration era. The Valentinos of Highland had a productive ice business into the early 1950s at Schantz’s Pond, and almost every clean fresh water lake was a source of ice if it was close enough to its end-user, or to transportation. Like the Yesses, many of the surrounding farms were run by first generation immigrants. The Buttennandts, Marie and Charlie, hailed from Itzehoe, Germany. Charlie was a chef by trade, and had worked in Brooklyn’s Hotel St. George and the Governor Clinton in Kingston, prior to settling into the farming life on Swartekill Road, in Highland in 1938. There they raised milk cows in a pristine barn that was regularly certified by the Department of Health so the farm’s milk could be sold to local hospitals. One of my earliest memories of their farm was petting a just-born calf—the wonderful smell of her sweet breath and feel of her rough tongue on my hand. The Buttennandts branched out to raise chickens, and later sold the milk herd, focusing on eggs and chickens. Their farm eventually boasted the “most highly mechanized chicken coop in Ulster County.” It was a huge cement block affair atop a hill filled with the cacophony of hen chatter. The building had a gravity conveyor that took the manure slurry underground, then under Swartekill Road, depositing it into a lagoon specially constructed for the purpose of decomposing it and mitigating the odors, not to mention lessening the work of disposal. Not all chicken farms had the neighbors’ olfactory well being as a prime driver. I recall the air on many a summer day along Route 9W near Ulster Park, air filled with a stench that seemed like some kind of chicken retribution for eating eggs. Chicken and cow manure were the regular field fertilizers and there were no complaints from those of us who understood how food came to our tables. Also, as a new driver, you learned early not to crowd the manure spreader being tugged along by an Allis Chalmers or John Deer tractor on its trip to or from the fields. Nor did you try to pass it… Candling eggs with Marie, I learned about the “other” fertilization (blush). Candling eggs was done by holding each egg up to a strong light and looking for any dark spots indicating the egg had been fertilized. Those were not sold unless it would have been to a brooder. Later, the chickens were kept in individual cages and the need to check so carefully was gone. Neighbors to the west on Plutarch Road, the Wolf-Weiler family, had come to the area from Israel in the late 1940s. They were an ambitious and exceptionally well educated group. I loved to listen to them speak, even with their accents you knew they loved language and its variety. They raised chickens and took in summer borders. On ebay I found a letter to them from a prospective boarder who was concerned that his new-born baby girl would not be charged board when then came that sum- mer. I traced the sender and sent a copy of the letter to the “baby.” She was delighted as was her father. The original letter was sent in the 1950’s. The letter writer and his daughter now live in Florida. Agnes Weiler Wolf wrote plays and books about her childhood in Germany, going to Israel, and immigrating to America. She went back to college and became a teacher at the Campus School in New Paltz. Another neighbor to the north was Max Meerkirk, known as the “bee man.” Max was also German, and good friends with the other refugees. It is reported that he brought the first pure bread Weimaraner to the US. Later, he and his wife moved to Washington state. Their legacy there is a public Rhododendron Park. Max removed a feral colony of bees from our house around 1950. We ended up with a huge galvanized zinc tub filled with honeycomb—another harvest of olfactory delights that colors my rural childhood. I interviewed Joseph Indelicato, whose parents farmed on South Chodikee Lake Road, Highland, since the turn of the last century, about the ever-interesting character, Levi Calhoun. Levi was such an interesting person that there are New York newspaper articles about him. He has been written up in every local paper more than once, including this one. Joe recalled, “He (Levi) was a wild- looking guy, 5’7″, compact. Very light blue eyes.” Joe said Levi’s mother was “wrinkled,” and “always hoeing in her garden” on Lily Lake Road. The Calhoun children included Pete, Luke, Carrie, Levi and seven others. Levi called Luke “the fox of he family” because he ended up with the family land. “Speaking of fox,” Joe told me, “Luke got two foxes with one shot— it seems they ran together into a cave and Luke just shot into it, luckily bagging them both.” Joe, Pete, and Levi fished for eels and the Calhoun brothers told all kinds of stories on these trips, including that Levi had hauled grain to the gristmill at Chodikee Falls, (the mill today is just a ruin). Joe said, “They caught about 100 pounds of eel and Pete carried it out by himself.” They used tongs to put the eels in the grain bags (eels are slimy) and would haul them to be sold in Highland or New Paltz. “Levi fenced in a section of the stream behind his house and kept live eels for his own consumption. He always had fresh eel for dinner,” Joe remembered. “Many other people, including George Muller, the local druggist, took eel from the Chodikee Lake and its tributaries.” It was a good food source. A Walkway Over the Hudson information sign on young or “glass eels” at one time plentiful in all the rivers and streams tells us the eels spawn in the Sargasso sea and migrate here to develop.  Levi Calhoun A wonderful series of photos done by David A. Pazda in the late 1960s for a college course at SUNY New Paltz on aging, shows Levi in his environs. This is one of my favorite photo of Levi from David’s collection. Once, Levi needed wood delivered and Joe hauled it in his truck. It was on that trip that he first got inside Levi’s house. Levi’s intruder alarm was a cow bell hit by the door opening. The house itself was covered on the outside and roof by gallon cans that were either crushed flat or cut and flattened to make shingles. The bedroom had a window so Levi “could see any meat coming off the (Illinois) mountain.” Levi harvested ginseng and other medicinal herbs for a pharmaceutical company. His source was secret. Joe Indelicato has an amazing collection of vintage farm equipment that was used by his family and others. My favorite is a plow built for grape vineyard cultivation that could be set to accommodate any vineyard’s hill sides. Joe worked for IBM for many years, but never stopped farming. He used a set of mules in his vineyard until a few years ago. He and Marlborough farmer Howard Quimby also used mules to take a utility pole up a steep vehicle-impassable mountain side for Central Hudson. (Howard gave me the newspaper article on page 15 about a farm his great-grandmother sold. Howard has been interviewed previously and is a source of many stories).  Jackson Heywood Baldwin Another Marlborough farmer I had the pleasure of meeting is Jackson Baldwin. Although Jackson’s daughter is now the main family farmer and does a brisk business supplying homemade jams and jellies, Jackson tends and picks the berries. As he approaches 99, on October 27, he is still a farmer at heart. Life wasn’t always so sweet for Jackson Baldwin. During the depression, he was on a train with some hobos looking for work when they were all arrested and sent to jail. The arresting officer wanted to let Jackson, go, but he said, no, he would go to jail with the others thinking there would be food there. It was the day before Christmas and the jailer did not want to feed them, so he let them all go. Hard for us to imagine that a meal would have been that hard to come by. Before taking off looking for work, Jackson’s life revolved around farming in Marlborough. Born in Rockville Center, NY in 1914, his family purchased the Marlboro farm in 1919. They had been on a trip to Windham, NY, when they got a flat tire in Middlehope. His parents saw a “farm for sale” sign and were soon in contract. The farm, 40 acres on each side of Route 9W, grew Keefer pears, grapes and apples. His father continued to work as a woolen-goods salesman and initially rented out the farm for $125 a month. When the tenant farmer was unable to pay, Jackson’s father quit his sales job to take over the farm. It was very difficult work in a very difficult decade for farmers. He tried get his sales job back, but like so many others seeking work in the 1930s, it was to no avail. He kept farming. Jackson’s father died suddenly at age 53 of a perforated ulcer. It was spring and life had to move on. His widow and three sons were now the farm’s only help—there was no money to hire hands. Twenty local farmers swept in and trimmed all the fruit trees on the entire farm, readying them for that year’s crop and eventual harvest. Jackson had quit school and worked “sun up til sun down.” Even so, there was just no money, “…peaches were 45 cents a half bushel, apples between 85 cents and a dollar per bushel, currents $40 a ton. The farm just about broke even,” he said. Related memories of those tough times Jackson recalled was of another neighbor giving them 500 young tomato plants. The harvest garnered the family 25 cents for each 12-quart basket—lots of work, but little cash. They bought the baskets at the Buckley Basket Factory in Marlboro. Many other farmers harvested yellow poplar to supply that factory and the other in Highland. Poplar was most easily steam-formed into pliable basket making strip. Another memory Jackson related was that at some point the Baldwin family “bought” a Model-T Ford from a neighbor, paying him entirely in proceeds from their raspberries. When the Baldwins finally could afford help on the farm, it was at one dollar a day, and the men mostly came from Newburgh. At that time eggs cost 25 cents a dozen and butter 35 cents a pound. Jackson also peddled chickens and grapes to the workers at the Roseton brick factory on the Hudson River. He said, “The workers there were mostly Blacks, Hungarians, and Greeks.” Jackson “hit the road” often to see if he could find work to sustain the family. Once, he landed in Florida as the first mate on a tour fishing boat. Always open to opportunity, he then sold the fish that guests did not want to take. Jackson spent one winter there. After returning to Marlboro, he took a truck load of apples back to Florida and sold them. Harvesting $500 from the Floridians, he sent $400 home. Then he sold the truck and headed to California. After some adventures in “rail travel” that included more hobos and police, and bus travel that included the bus hitting a mule and a horse in Texas, Jackson ended up back in Marlboro in time for spring work. In the 1940s Jackson and his wife, and Jackson’s brother started Baldwins Farm Market on Route 9W in Marlboro. Eventually his brother took over the farm and left the farm market business for Jackson to run. They sold the stand back to his brother because Jackson had started another enterprise: building and land-lording. Jackson said he was not cut out for that business and returned to faming. The new farm business, “Jaxberry Farm,” grew organic greens and berries which were sold to restaurants, markets, and the Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park. He said the acreage that he farms today has shrunk considerably, but not his love of farming. Thank goodness.

Nicholas Poultry Farm, Rifton

Rail Station in Kerhonkson |