Imagining John Pizzo

Fall 2012

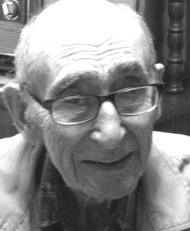

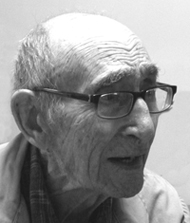

It’s hard to imagine that a man could live on a farm for a hundred years and not have been born there. A man, over 100, who has no need of glasses to read this print, a man, over 100, who has an impish smile filled with perfect, natural teeth.

It’s hard to imagine a man over 100 who can so vividly remember the long gone past and yesterday’s news.

But, I didn’t have to imagine. John Pizzo sat before me.

“It’s pronounced Pie-zo” he articulates for my benefit on meeting him, December 22, 2011. Then, about to celebrate his 101st birthday on December 27th, John tour-guided me through his life, starting with his parents’ immigration from Sicily to Tampa, Florida, and their decision to move from Tampa to Marlboro, New York, when John was three. And then, the next 99+ years of his life on the farm his parents eventually purchased… (John will be 102 in December 2012).

“It’s pronounced Pie-zo” he articulates for my benefit on meeting him, December 22, 2011. Then, about to celebrate his 101st birthday on December 27th, John tour-guided me through his life, starting with his parents’ immigration from Sicily to Tampa, Florida, and their decision to move from Tampa to Marlboro, New York, when John was three. And then, the next 99+ years of his life on the farm his parents eventually purchased… (John will be 102 in December 2012).

Both born in Saint Stefano, Sicily, Italy, John’s father, Guiseppe and his mother, Emelia Zambito, immigrated to the United States. He in September of 1903 at the age of 17, and she in February 1907 at the age of 16. Touring the Ellis Island archives we discover his parents’ ports of departure and the ships’ names—Emilia’s, the Sicilian Prince and Guiseppe’s, the Hohenzollern—on which they arrived. Guiseppe joined his sister Guiseppina, settling initially in Tampa, Florida where he worked in a cigar factory. Emilia also set off for Tampa on arrival in America.

In Tampa, the now married Pizzos were constantly ill and suspected the tobacco dust and molds they were exposed to working in the cigar factory. Fresh air was not circulated because it would have dried out the tobacco leaf and made it unsuitable for rolling into cigars. A friend suggested the Pizzos take a vacation to sleuth out whether it was the stale air of the factory making them ill or some other cause.

The dining room of the Chillura’s Hotel, Marlboro, NY, circa 1930. This is where John Pizzo’s parents made the decision to move to New York.

Luckily for the Pizzos, relatives in Marlboro, NY, owned a large popular boarding house called Chillura’s (its dining room postcard image is from 1930s). The couple’s visit improved their health—they felt much better in the clear New York air. And so began a search for a small farm. In 1914 they found an abandoned farm boasting a few neglected grape vines. They purchased the land and set out strawberry plants because that was a crop that could develop in one season and bring money right away, unlike apples, peaches, cherries, or grapes, which took years, John tells me.

The Pizzos’ farm had a shack large enough to house a cow and a horse. They raised chicks in a brooder (a commercially built container with a heating element to keep eggs or chicks from freezing when there was no hen to keep them warm). One night the Pizzos forgot to turn the heater down and it started a fire that destroyed the shed. A calf and all the chicks were lost. More important to the small family, its cow and horse were unhurt. Losing the shed was still a huge blow to the struggling young family. “Guiseppe was despondent,” John informed me.

A family friend asked Guiseppe, “Do you like it here?” To which Guiseppe reportedly said he did. “Then we’ll have a barn-raising,” his friend declared. And they did. The friend, Bill McElrath, had saved enough old beams from a dismantled barn to put up the framework for the structure and neighbors showed up to do the work. The result was a suitable home for the horse and cow.

In addition to farming, Guiseppe traveled to NYC to do piecework in the cigar factories making cash to purchase things the family could not make themselves. While Guiseppe was in NYC—mostly during the winter, Emilia took care of the farm animals and the growing family. The farm had no electric service until the 1930s, no running water in the barn or house, meaning Emilia carried water from a well for the family and the barnyard animals. The house was not insulated—its single source of heat generated by a potbelly stove that required feeding wood day and night. Emilia was a busy woman alone on an isolated farm in winter with negative temperatures we rarely see today. I try to imagine Emilia Pizzo’s life after her early years in sunny Sicily and Florida—living in the hinterland of Marlboro—no electric, no water, no central heat, and four small children. In all, the Pizzo family eventually numbered four girls, Mary, Jenny, Angela, and Lillian, and one boy, John.

John Pizzo’s old friend and fellow farmer, Howard Quimby, is with us in John Pizzo’s tight little house. Howard’s brother, the late Sam Quimby, is the person who suggested I might enjoy meeting John. Howard acted as the intermediary.

Watching the shared history of these “Marlboro men” is more than pleasant. Howard, though, is a “spring chicken” of just 83 years at the time of this interview.

Subjects come from both men and then they reminisce taking me to a time I can not recognize.

“There were no plowed roads of course,” so going to school “was horrible.” Discussion ensues as to when the town actually started plowing local roads. They muse on the depth of snowfalls “back then,” compared to how little we see now, and somehow we get back to electricity. Howard’s family used a battery powered generator into the 1930s. To have Central Hudson service they would have had to install two poles on a neighbor’s property. The neighbor would not let that “new outfit,” Central Hudson, put up the poles. That reminded me of my friend, John Indelicato of Highland, who told me about how he and Howard Quimby “used mules to pull phone poles up Illinois Mountain in Highland because only mules could get up there.” That was in the 1980s.

All of the long-time farmers have lives that intertwined around crops, shipping, animal husbandry, the weather, and helping one another, in small and sometimes very big ways. Indelicato, whose family farmed the area for generations, has a vineyard on South Chodikee Lake Road that looked like geometry in its perfection. He plowed it with his mules.

The subject switches back to school. Another pot belly stove, this one’s fire built by someone every morning before the students arrive. One room. Grades first through sixth. John Pizzo comments that he walked two and a half miles to school, one time in a “miserable cold only to be told by the principal, Mr David D. Taylor, to warm up and then go home.” No school that day because of the bitter temperature. He adds that he never did ride a school bus.

John did not go to Marlboro High School with his class mates. He worked, now full time. He had worked “part time from the age of five, picking and packing fruit.” In his early full-time farming he used a horse, cultivator and plow. John tells me , “Grape pruning is a poor man’s psychiatrist—relaxing, focused, and purposeful.” In fact, he still does a bit of it. In his back yard is the manicured vineyard of what was his family’s farm. John goes out when the weather is agreeable and tends the vines by his house. John Indelicato and Howard tell much the same story about the vine culture’s mental health benefits. I am convinced.

This photo of John Pizzo was taken August 19, 2012, eight months after our interview. While I was there, his neighbor, Carl, stopped by to chat and I suspect to make sure John did not need anything. John is that kind of person—you just can’t help wanting to see him again.

The conversation swivels to the new apple varieties. The men tell me it used to take 10-15 years for an orchard to come into peak production. “The varieties planted today do that in a year or two,” John says, “and the trees remain short.” The smaller trees mean the pruning and picking are faster and less dangerous—no ladders.

Some of Howard’s grapes help supply a local vintner and they have named a wine variety for him, Quimby Rose. He reports the current winery owners are very good farmers and keep their vineyards well-tended. I think to myself that with these two and Indelicato on the prowl, who would not keep their vineyards well-tended?

Of course farming has changed dramatically since John started working on his parents’ farm and from the time he purchased his own acreage. With a $9,000 bid he purchased a 41-acre farm that was in foreclosure. He and his wife, Mary, “started off there with raspberries, about ten acres,” he says. They did most of the work themselves. During harvest, John would “drive his truck to Newburgh and hire 25-30 kids, bring them to Marlboro, harvest berries, and then return the crew to Newburgh in the evening.” Hard to imagine all the red tape you would have to endure today to do such a thing, let alone finding youngsters willing to work that hard, and parents willing to let them.

John tells me the house sheltering us from December winds was designed by him and his wife “just the way we wanted it, all plaster, too,” and built in 1934. The house John grew up still stands up the road and was built using timbers that came from razed buildings.

“My parents said to us kids, you want to live in a new house you have to help earn the money. We planted and harvested $3500 worth of raspberries and built the house. Imagine that. $3500. That’s a lot of raspberries,” John mused.

I asked about other remarkable things they remembered. Howard said he heard about, “When the Methodist church burned, around 1913, the sparks flew over to the Presbyterian church, lighting its steeple. The firemen went over to the burning steeple, cut it away from the building and pushed it over, saving the rest of the church. You can still see the charred beams inside the church. They didn’t rebuild the steeple.”

John has a lot of plaques honoring him, some from his town, his county, and his church. “I have a whole bag of plaques, very honored.” John smiles. Howard opined that it is “rightly so, John has done so much for the community.”

“Time goes on, changes everything,” John says. “Sure does.” Howard agrees and they are quiet.

“The Fruit Exchange took over the old school where they had held classes in the attic. What a fire trap.” Howard recalled.

John continues the thought, “Button factory, that was a school, too.” We continue on the school theme: Favorite subjects? John’s was math. Howard’s was geometry. I find it fitting that these men who have had to farm by the rigors of a fickle mother nature should find beauty in the consistency of numbers.

John starts a new thread about building things in the “old days.” Especially the work to build using cement. That amazes him, he says. Howard continues, “Elmer Yeaples mixed all the mortar by hand to build the Quimby barn in 1913. He used a hoe and wheelbarrow.” We ponder that for a moment, all picturing the size of that structure’s foundation. BIG.

We wind our way back to the past. “Mailman delivered with a horse and buggy. You could set your watch by him. Gus Cotant. He’d stop and feed his horse and eat his own lunch—in winter, people on his route would invite him inside to eat.” Howard recalls.

Back in time, taking me with them. Howard: “Neighbors shoveled out the church.”

John: “Farmers worked on the road so they had lower taxes.”

The thing that changed John’s life the most?

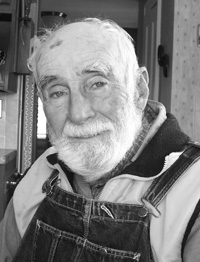

Howard Quimby

“When farming went from handwork to tractors.” The remark reminds me that in 1900 more than 90% of the population was involved in farming. And we needed every pair of hands. At the close of that same century, it was less than two percent. I think of the multitudes who were freed from hard farm labor to bring the rest of the industrial revolution and the comforts of today. I think of how hard today’s farmers still work to feed so many more of us.

John and Howard marvel at the world they helped make. And we marvel at them, not so much for having lived long, but for how good and well they have lived.