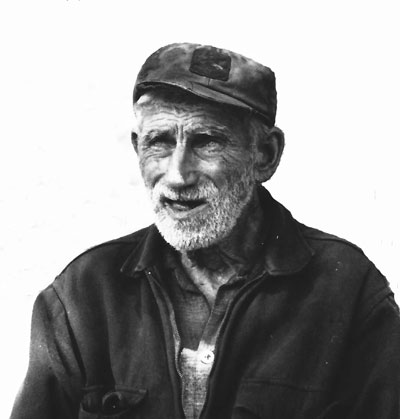

Levi Calhoun

based on a previous About Town article

Fall 2018

Levi Calhoun photo courtesy of David Pazda who as a SUNY student did a series of Levi photos and gave permission to use them.

As I look at this photo of Levi, I am suddenly a five-year old standing at the edge of an unpaved road. It’s 1949.

“Poison ivy,” Levi says knowingly. His incredible aquamarine eyes survey the ravages of the plant’s oil on my arms.

“Stay,” he commands, and carefully lays his bicycle on the grass next to our drive. He walks down past the Auchmoody Cemetery into the Great Plutarch Swamp. As he disappeared in the cattails, my mother joins me.

Levi returns with several stalks of a lush plant—roots, leaves and flowers. As he walked toward us, he crushes the plant, turning it into a pulpy mass, juice running over his not exactly manicured hands.

My mother blanches as he proceeded to rub the ooze down each of my outstretched arms. It felt fine.

“Jewel Weed,” he announces triupmhantly when I was oiled to his satisfaction. Smiling toothlessly, he mounted his bike, and was off.

My mother was off.

In an instant, the Jewel Weed was off. With water running over my arms, my mother explained it wasn’t the medicine she doubted, just the delivery system.

She found a fresh stand of Jewel Weed, followed Levi’s example, and re-anointed my arms. To this day, calamine lotion is relegated to my “winter” remedy for poison ivy. (You can get poison ivy in the winter–the oil is in the vine, as well as the leaves.)

My mother said Levi tended bee hives near our house and that was why he traveled our road so regularly. It may also have been that he knew where the ginseng grew, or some other exotic that was paid for by the ounce. A true naturalist-mountain man, Levi knew his plants, which explains why my mother didn’t throw the baby out with the bath water. But there is so much more to Levi and his lore than just his woodsy culture.

When one of his sisters did not come to school for a very long stretch one winter, the truant officer asked Levi where she was. Levi announced the girl had died and was stored up in the barn until the ground thawed.

The last time I saw Levi was in 1976. He was clean. Hair, face, hands, clothes. So clean, it took me a moment to recognize him. Then I saw his eyes. He smiled. He had just come out of the hospital he said. I had heard he had been hit by a car while riding his bicycle. We chatted. Parted.

“Levi has died,” Lloyd historian Bea Wadlin told me with gravity and sadness. A legend gone. It was Spring, April 4, 1976. The ground is thawed I thought and I was glad for him. “There’ll never be another Levi,” Bea said. For sure.

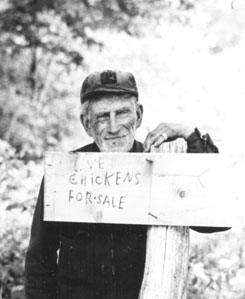

Levi Calhoun with “Live Chickens for Sale” sign in front of his home. Circa 1960s. From the collection of Vivian Yess Wadlin

There is plenty of other Levi lore. Born January 20, 1889. Grew up dirt poor or dirt rich, depending on how you think about it. Mutli-siblinged to the tune of 18. As an adult, lived in a bunch of shacks with his goat, dogs, chickens, and whatever. Married once in 1912, but the new wife couldn’t cook, so he took to the bachelor life. Served in World War I, honorably discharged. His name appears on the flag pole monument in the hamlet of Highland. He never had electricity, indoor plumbing, or modern transportation. The latter didn’t matter. Levi could run. And did.

There are stories about his races, one even turned up in the New York Times, and stories about his natural cures, and stories about his hermit-like existence, and stories about the wise, off-color, or funny things he said or did.

Area resident, the late John Jacobs, is quoted in a Poughkeepsie Journal article by Bond Brungard, “Levi asserted to me that it was OK to be eccentric, that you didn’t have to be a square peg in a round hole, that you can make your own square hole.”

The lasting magic of Levi is that he was a human shuttle weaving a colorful, warm, tapestry into our community. In traveling by bicycle throughout Highland, Esopus, and New Paltz he wove us into a more cohesive, more interesting fabric. He gave us a common ground that didn’t threaten or force, require or request, but was simply played out for us to enjoy and to share with one another. Even now.

The About Town Tiney Trolley in Highland is dedicated to Levi’s memory. He peeks out the doors.