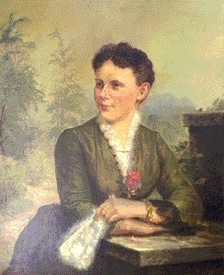

Miss Ganse by Lilly Martin Spencer

Lilly

Spring 2013

|

Ten years ago, SUNY New Paltz Professor Bill Rhoads asked me if I knew the location of “Rock Nest,” the Highland (Town of Lloyd) home of artist Lilly Martin Spencer. I did not, nor was I familiar with the artist. As it turns out, I should have been, and for a number of reasons.  Miss Ganse by Lilly Martin Spencer From the name “Rock Nest” and a photo Rhoads shared from the Town of Lloyd Historian’s office, we expected to find Spencer’s home perched high above the Hudson River. Enlisting my husband to check Ulster County deed records for Hudson River property owners in the Town of Lloyd, he found a parcel in Lilly Martin Spencer’s name. A reference in Lilly Martin Spencer: The Joys of Sentiment, published by the National Collection of Fine Arts (Smithsonian Institution Press 1973)*, places Spencer in Highland at “Rock Nest” by 1879. The deed places Spencer’s land north of the Bob Shepard Highland Landing Park. However, from the deed description, the property did not go to the top of the ridge that runs above the Hudson. When we viewed the property from the public road, there was no indication of “Rock Nest” ruins and from the photo, the structure appears rather large. (If you have a clue, please let us know!) A second site mentioned for the Spencers had them in 1892 living at “Blue Point” in Highland, but described as eight to ten miles miles south of the “Rock Nest.” However Blue Point Road in Highland is far less than that distance. The mystery of “Rock Nest” will have to wait for another day. Spencer was a prolific and popular artist who resided with her husband and many of their 13 (!) children in Milton and Highland until her death in 1902. Of their children, only seven lived to adulthood, with one having a last address at a NJ psychiatric hospital and another at the Hudson River Psychiatric Center just north of Poughkeepsie. (I’ve often wondered if Spencer’s use of lead-based white paint may have doomed her children to early death or mental infirmity, and if she chose to live in Highland because the Hudson psychiatric institution would have been visible from her home). Spencer was famous in her day for portraying scenes of “everyday life”—some romantic, some humorous—families enjoying each other’s company, and often, portraits of women or children. Her most favored work showed women of middle class means in their orderly domains—kitchen, nursery, living room—occupied in domestic tasks and sweetly enjoying them. A book by Wendy J. Katz, titled, Lilly Martin Spencer, explains the political and social era of Spencer’s work, and the modeling of important individual, social, and civic values in her paintings, something easily overlooked in today’s cultural morass of limited self-restraint. In almost all of her paintings, Spencer set a tension between some seeming disorder (children “stealing” fruit from the table set for dinner) and the order of the good home about to be realigned by the woman and or mother. According to Katz, the disorder engendered by the children in their self-centered actions needed the socializing hand of the woman to teach them the proper etiquette for a better life. But etiquette had a more encompassing meaning then. Indeed, during Spencer’s most prolific years, many others were writing and selling etiquette books to help the expanding middle class make those important adjustments to their improving station in life. Spencer sold rights to print copies of her work and they became the affordable lithographic-centerpieces of many a sitting room. She was the most popular female artist of the mid 1800s and her art appeared in Godey’s Lady’s Books, the “Elle” of the era. Married at 22, Lilly was the breadwinner for her large family. Her husband, Benjamin Rush Spencer, managed her career, helped with her painting (probably did backgrounds), the children and their home, though he did, early on, work outside those confines. He was trained as a tailor. Spencer’s work also provides us with the likenesses of many notables, including some from well-to-do Poughkeepsie and Kingston families. A few years ago at a friend’s home, a portrait of two young girls struck me as particularly well-done and lovely, and somehow familiar. There was an apparent antagonism between the two children, with the younger child expression unhappy about something, making them appear more unposed and real. Noticing me standing before the large canvas, my friend explained, “Those are my great-aunts. According to family lore, sitting for the portrait was tedious, and the younger one didn’t want her sister’s arm around her… that’s why she looks so unhappy. It’s by Lilly Martin Spencer.” My first real Spencer. Lilly Martin Spencer had stood before this canvas, she knew my friend’s family. Spencer’s life was becoming less and less a creature of the page to me. My friend continued, “That other picture isn’t signed. I don’t know who she is.” “Did you know Spencer is buried in Highland? I asked. “She lived there until her death in 1902.” I didn’t know the exact location of her grave even though she shares the large cemetery with my husband’s family, among many others. Now, I would find Lilly’s grave and pay my respects. The second painting of a single child leaning on a fountain resonated with me the same way the confirmed Spencer had, and I was pretty sure it must also be by Spencer. But, why wouldn’t it have been signed? Later, with additional research, I found another Spencer painting that incorporated what appeared to be the same fountain. Both paintings had flowers so similarly executed, they could have been in the same picture. I also learned there is an 1883 “unlocated” Spencer painting of a child with the same name as one of my friend’s aunts. And it is an unusual name. Lilly’s given name was Angelique Marie Martin. She had been born in Exeter, England in 1822 to French parents who believed in education—even for girls. The Spencers were also staunch abolitionists and a few of Lilly’s works have been cited for seeming to convey particular sensitivity to slaves of all colors. The family immigrated to America in 1830 settling in Marietta, Ohio, where Lilly was encouraged to pursue an obvious talent—drawing and sketching. She would eventually study with portrait painter John Insco Williams, James Henry Beard, and William Althorpe Adams. According to the book mentioned earlier, Lilly Martin Spencer: The Joys of Sentiment, Spencer’s work had been positively commented upon by Asher Durand among others. While still in Ohio, Spencer had been offered the chance to study in Europe courtesy of a wealthy patron, but she declined. She was named an honorary member of the National Academy of Design in 1850. Spencer’s work was probably last exhibited in any meaningful way, in the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, but the market for her style and subjects was eroding. She continued to paint, mainly portraits and commissions, until her death in 1902 in New York City. Paintings from the height of her career are still available as prints. To find the Spencer burial place, Lloyd Historical Preservation Society president and 19th and 20th century art expert, Charles Glasner, and I contacted Roger Gardner, the caretaker of the lovely Highland Cemetery on Vineyard Avenue (44/55) south of the Highland hamlet. We asked if he could direct us to the grave. Consulting his meticulous card file, Gardner took out a postcard of one of Lilly’s most famous paintings. “We Both Must Fade” (1869). It shows a very lovely young woman holding a flower and looking wistfully into the distance as though through time. Roger lent the card to me to reproduce for this story. (See page one). Gardner told us that in addition to Lilly, others buried at the monument are her husband, Benjamin, who died in 1890, and their children Charles Francis (1928), Flora (1934), and Pierre Alexander (1947). Of the Spencers’ seven children who survived into adulthood there were five boys and two girls. The Spencers’ monument is an unremarkable stone, taller than most, but still modest. The three of us stood for a few minutes talking about Lilly and her life and art. Charles and I vowed to come back and clean the stone. In our earlier search of deeds for the Spencer’s “Rock Nest,” we found the property north of Highland Landing had been foreclosed upon in 1894, one year after she had deeded it to four of her children. That may have been when the family moved to Blue Point or to Milton, NY, but we don’t have dates for their Milton life. It is believed Lilly was involved there with Elverhoj, the artists’ colony that flourished during the late 1800s into the 1900s. Lilly had also painted still lifes, landscapes, and miniatures. The lack of money was a recurring theme in the Spencer’s lives even though Lilly turned out paintings in great numbers—the location of many are unrecorded. Spencer paintings turn up in sales and galleries, most recently a pair of small still-lifes. In addition to local portraits, Spencer painted the likeness of notables of the day, including Robert Ingersoll, a famous agnostic orator whose devotees still maintain his home as a bastion of free thinking (ideas ought to be based on reason, logic, proof and the not dogma of the political pundit, the press or the pulpit) in Dresden, near Seneca Lake, New York. Spencer also produced the portraits of First Lady Caroline Harrison and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, champion of women’s rights. Thanks to the 1973* retrospective exhibition of Spencer’s work at the Smithsonian’s National Collection of Fine Arts in Washington, DC,- she is today respected as one of the leading genre painters of her time.

*Exhibition held at the National Collection of Fine Arts, June 15-Sept. 3, 1973. Lilly Martin Spencer, 1822-1902; the joys of sentiment by Robin Bolton-Smith and William H. Truettner, assisted by Cynthia D. Perlis, directors of the exhibition. |