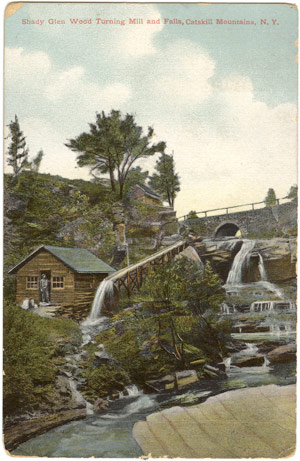

Bishop Falls card is very early, possibly 1904 as the back is for address only.

Milling About

Spring 2011

I asked my dear 93-year-old friend, Wilson Tinney, what he remembered about mills in Ulster County.

“Wherever there was flowing water there were mills,” was his reply. In researching this article, I find he did not exaggerate. Carpet mills, paper mills, saw mills, powder mills, grist mills, cider mills, cement mills, carding mills, knife mills, feed mills, knitting mills, and others nested along fast flowing streams or the diverted flow of rivers to feed and clothe a growing nation. Steam driven mills were also widespread sources of mill-power. Ulster County’s many waterways, including the Wallkill, Twaalfskill, Shawangunk Kill, Jew’s Creek, Coxing Kill, Black Creek, Esopus, Rondout and many others, provided the water power that made the area exceptionally productive from the 1700s on. Added to those abundant power sources was the ingenuity and ambition of the men and women who came to this country and to this area seeking to build a better life. (The text on the postcard below tells its own story). The history of mills is one of continuous hard work and successful businesses punctuated by floods, fires, wars, and economic turmoil.

“Wherever there was flowing water there were mills,” was his reply. In researching this article, I find he did not exaggerate. Carpet mills, paper mills, saw mills, powder mills, grist mills, cider mills, cement mills, carding mills, knife mills, feed mills, knitting mills, and others nested along fast flowing streams or the diverted flow of rivers to feed and clothe a growing nation. Steam driven mills were also widespread sources of mill-power. Ulster County’s many waterways, including the Wallkill, Twaalfskill, Shawangunk Kill, Jew’s Creek, Coxing Kill, Black Creek, Esopus, Rondout and many others, provided the water power that made the area exceptionally productive from the 1700s on. Added to those abundant power sources was the ingenuity and ambition of the men and women who came to this country and to this area seeking to build a better life. (The text on the postcard below tells its own story). The history of mills is one of continuous hard work and successful businesses punctuated by floods, fires, wars, and economic turmoil.

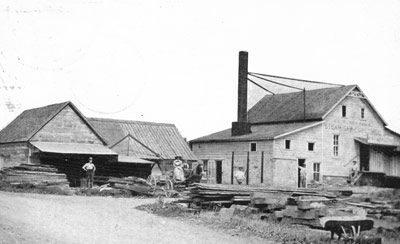

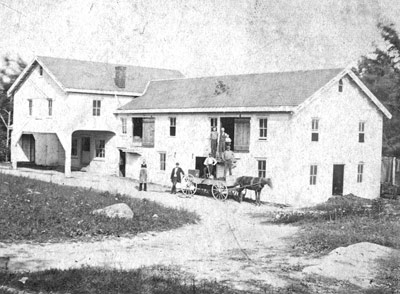

Gardiner, NY. John S. Rosekrans built a feed store, and later a saw mill and grist mill run by steam. Built in 1883, the mill was destroyed by the terrible fire of 1925 that devastated much of the village. Note the beams and lumber at right. Text above from card back:

Jan 26th, 1912, Gardiner, NY

Hello Will, How are you. Got your card to day. This is the plant that makes me all the money that I spend now. It is right over the road from the one you learned to be a millwright in. Yours, JS Rosekrans

Sent to Wm B. Marquette, No 94 Hamilton Place, NYCity

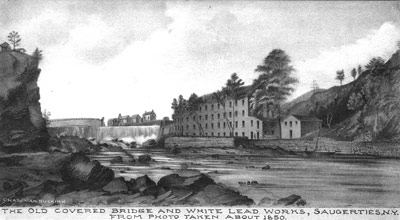

Edward Clark started the Ulster White Lead Works in the town Saugerties (Glenerie) in about 1835. The business ground lead powder to be used as a paint additive. The water-powered mill took discs of lead which had been corroded with vinegar and ground them to powder. The lead made the paint white, but was toxic (hatters also used lead to process material and gave us the expression “mad as a hatter”). According to the book Saugerties: Images of America, by Edward Poll and Karlyn Knaust Elia, the plant was known as “slow kill” by its employees. White Lead Works closed in 1900.

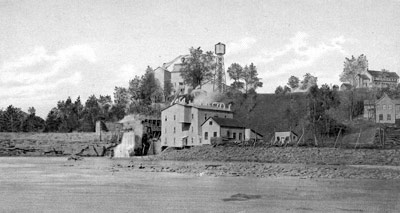

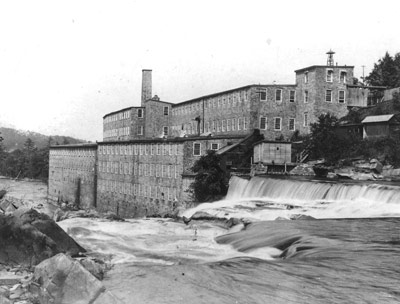

Saugerties had many other mills, most notably, the Cantine Mills (founded 1888, closed in 1977 and destroyed by fire in 1978), Scheffield Paper Mill, the Diamond Paper Company mill (pictured below), and the pre-Revolutionary, Terwilliger grist mill in Seamon Park.

Diamond Mills Paper Company, Saugerties, NY, built 1894. It was increased in size and operated under a number of names. Saugerties was known for fine paper, but with changes in printing techniques and the kinds of paper it could produce, Diamond lost customers in the ever evolving market place.

In the History of the Town of Marlborough, by C.M. Woolsey, mills included the grist and saw mills built between 1760 and 1770 by Edward Hallock on Hallock’s Brook in Milton. Leonard Smith and his son, Anning, had a woolen factory, a saw mill and grist mill in Milton. Two grist mills built by Major Lewis DuBois were located in what is now the Village of Marlboro, and Charles Millard “had a saw mill on Jew’s Creek. He sawed lumber for people, and also sold and shipped lumber. In 1809 he also had a grist mill there.”

“In 1815 John Buckley, who was an expert wheelwright, machinist and manufacturer,” purchased the Millard property and established a carding and spinning mill, eventually making cloth, including satins and broadcloths. With partners, James and John Thorne, it became known as the Marlborough woolen factory.

History of Marlborough mentions many other mills and is an excellent source of family names and places for the area. Another source of mill lore, and much more, is Thank Rosendale by Peter P. Genero. He reminds us that “when taken in aggregate, they (mills) become quite important. The following is a summary of the water-powered mills operating within New York State prior to the opening of the Erie Canal:

| Grist mills | 2,140 |

| Saw mills | 4,321 |

| Fulling mills (textiles) | 993 |

| Carding mills (textiles) | 1,235 |

| Tanneries | 1,000+ |

| Total | 9,689+ |

He goes on to extrapolate that would have been approximately one mill for each 142 people.

In their book, Lost Towns of the Hudson Valley, Wesley and Barbara Gottlock discuss the largest settlement for property made by New York City in building the water system to slake the thirst of the growing metropolis. They report $112,000 was paid to John Boice for his gristmill at Bishop Falls on the Esopus Creek “for the property and water power he lost from the falls.” Also from the Lost Towns, we learn Bishop Falls was named for Asa and Rebecca Winchell Bishop who settled the area and built a mill around 1790. Asa was blinded by small pox as a child and learned milling from his father. “Jacob became known as the ‘Blind Miller,’ who, it is said never made a mistake at the mill.” Wilson Tinney also mentioned the blind miller, “Mr. Bishop was blind and it was said he could tell the color of a horse by feeling it.”

In their book, Lost Towns of the Hudson Valley, Wesley and Barbara Gottlock discuss the largest settlement for property made by New York City in building the water system to slake the thirst of the growing metropolis. They report $112,000 was paid to John Boice for his gristmill at Bishop Falls on the Esopus Creek “for the property and water power he lost from the falls.” Also from the Lost Towns, we learn Bishop Falls was named for Asa and Rebecca Winchell Bishop who settled the area and built a mill around 1790. Asa was blinded by small pox as a child and learned milling from his father. “Jacob became known as the ‘Blind Miller,’ who, it is said never made a mistake at the mill.” Wilson Tinney also mentioned the blind miller, “Mr. Bishop was blind and it was said he could tell the color of a horse by feeling it.”

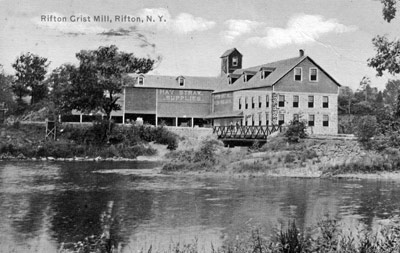

Wilson, who was born and lived in Port Ewen for 90 of his years, also told me, “The stretch of the Wallkill near Rifton had several mills—cotton, woolen, grist, a knife factory, a powder mill, and a charcoal factory that supplied the powder used in making black (explosive) powder. My grand-uncle, Ezekiel Eltinge, owned three or four mills on the Wallkill.”

“There was a button factory at the end of Hamilton Street in Port Ewen where they made the buttons from clam shells. As a kid, I used to dig up pieces of shell with the outline of a button cut into it.”

“There was a button factory at the end of Hamilton Street in Port Ewen where they made the buttons from clam shells. As a kid, I used to dig up pieces of shell with the outline of a button cut into it.”

History treasure abounds if you mill around in Ulster County. Ruins are everywhere, sources abundant.

Shady Glenn post card message: We are having a fine time but can’t buy many postals up here. Wish you was (sic) up here (,) it is just the place for a rest or lovers. Ada & Albert

The Newly Weds (1909?) Postmarked “Denver, NY” (Delaware Co.)

“The rifts in the stream

Gave Rifton her name.

The falls in the waters

Gave Rifton her fame.”

From The Town of Esopus Story (aka “The Red Book”) available from the Klyne Esopus Museum: www.klyneesopusmuseum.org

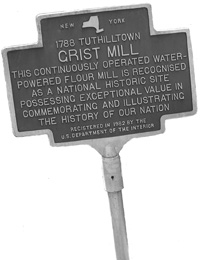

Tuthilltown Gristmill, built in 1788, is one of very few remaining mill buildings in Ulster County, and today houses Tutthill House at the Mill restaurant, Gardiner.

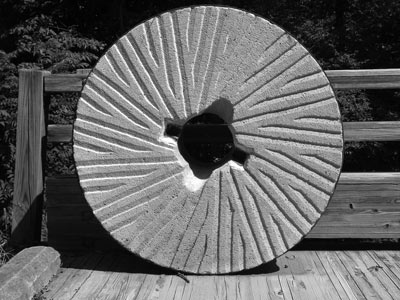

Millstone on dining deck at Tuthill House (gristmill) Restaurant.

The old covered bridge and white lead works, Saugerties, N.Y.

from photo taken about 1850

Yesterday and today at the Tuthilltown gristmill. Photo from around 1940, the miller adjusts the grind in the 1788 mill.

Yesterday and today at the Tuthilltown gristmill. Tuthill House at the Mill Restaurant as it looks today. This mill has been feeding us for a long time! The mill stone on the front page is outside the mill. Mill stones carved from nearby Shawangunk grit were considered among the best and were shipped all over the world. (Bricks made here, cement and bluestone harvested locally, were also sold widely, especially to New York City).

“Pulp Mill, Ulster County in the Catskills” 1904 post card.

Below Dimmik carpet and rugs mill at Dashville. Gone now, but a few foundations remain along Route 213 not far from Central Hudson dam on Wallkill. Post card from 1906.

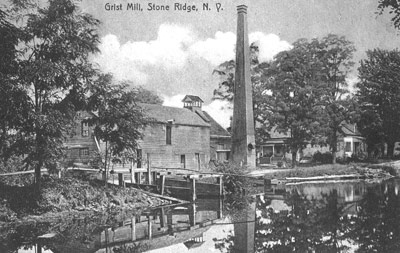

Grist Mill, Stone Ridge, N.Y 1909 post card. Postmarked “Kripplebush”

All images are from collection of Vivian Yess Wadlin except photos of Tuthill House Restaurant, and Tuthilltown gristmill interiors.