Kingston Post Office was demolished (1969) to build a Jack In The Box fast food restaurant. Building is currently empty.

Postal Roots

Winter 2019

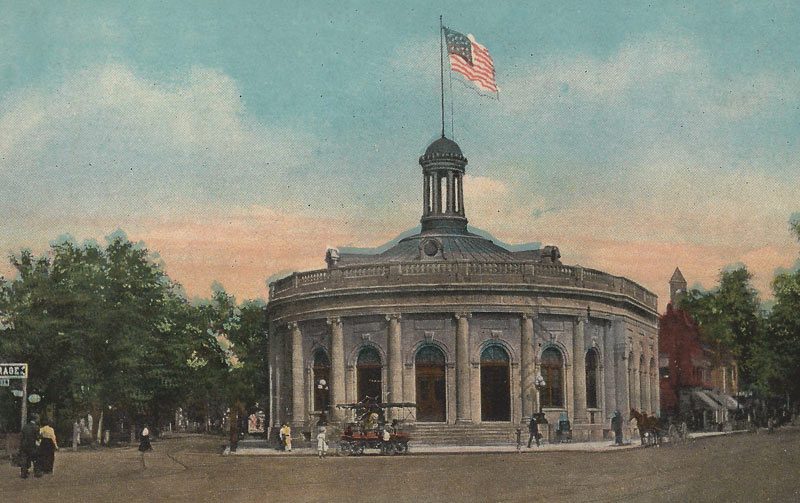

Karen Berelowitz and Stephen Blauweiss’ comprehensively researched, beautifully written, and lushly illustrated account of The Life and Death of the Kingston Post Office should be in the library of anyone who appreciates historic architecture and works to preserve it. The book is a memorial to that most beautiful post office building as well as a warning about how easily it was lost. The book is so much more. It is a history of Kingston and its other buildings– both saved and lost. It brings to mind poet, writer, and social critic, James Fenton’s quote, “It is not what they built, but what they knocked down.”

William B. Rhoads, emeritus professor of Art History, SUNY New Paltz, provides this perspective on the 1969 demolition of the Kingston post office in his book, Kingston, NY, The Architectural Guide,

Many Kingstonians express dismay at the destruction of the classical post office (1904) on Broadway, designed by James Knox Taylor. While its style derived from the European Renaissance, in 1904 it was called “distinctly colonial in keeping with our colonial city and its traditions.”

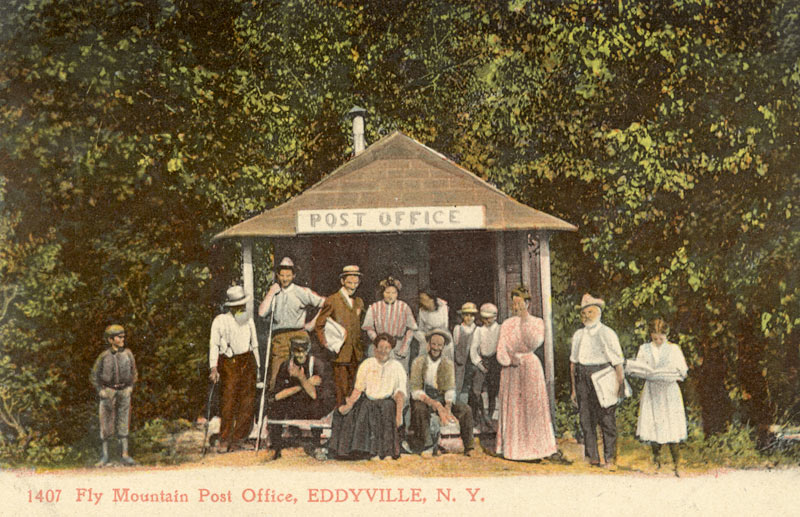

The two books sent me checking the many postcards in my collection featuring early local post offices. Cards indicate that these offices bounced around in small communities from homes to stores, and often back again, eventually coming to rest in buildings constructed for postal-purposes alone. But before that, everyone knew their postmaster’s name. And the postmaster had to know everyone else’s, as well. He or she really had to, as early mailing addresses were simply the recipient’s name and town or post office addresses, no street name, no box number. Early post offices were spaces, places, people, and services that shaped many lives, but got less and less public attention as the postal service became larger and more impersonal. Today, few of us know our postmaster’s name. And they certainly don’t know the thousands of us coming through their postal lobbies.

The two books sent me checking the many postcards in my collection featuring early local post offices. Cards indicate that these offices bounced around in small communities from homes to stores, and often back again, eventually coming to rest in buildings constructed for postal-purposes alone. But before that, everyone knew their postmaster’s name. And the postmaster had to know everyone else’s, as well. He or she really had to, as early mailing addresses were simply the recipient’s name and town or post office addresses, no street name, no box number. Early post offices were spaces, places, people, and services that shaped many lives, but got less and less public attention as the postal service became larger and more impersonal. Today, few of us know our postmaster’s name. And they certainly don’t know the thousands of us coming through their postal lobbies.

Yet, the postal history of the United States is a fascinating legacy. It is full of insights, human interest, and invention. And some shameful political backsliding which we will get to later.

Yet, the postal history of the United States is a fascinating legacy. It is full of insights, human interest, and invention. And some shameful political backsliding which we will get to later.

The changes brought to the postal service by outside technological advances were sometimes slow to be adopted because the government-decreed monopolistic postal system lacked early successful competition. At first, there was nothing forcing it to update more quickly. Then came the telegraph and telephone. Then, FedEx and Amazon. All in all, the United States Postal system has worked amazingly well for most concerned.

Postcards Images of Post Offices

According to rural route carrier and postcard historian, collector, and dealer, John Duda, the first picture postcards were from the 1893 Columbian Exposition held in Chicago. As early as the 1870s, Post Offices sold blank cards with postage printed on them. (The first US postage stamp was issued in 1847). Specific regulations for postcards were passed by Congress and cards during that era had to be marked “Private Mailing Cards.” After 1901, cards no longer needed that phrase on them. Unlike cards today, the back of an early card could have nothing more than the recipient’s address and a stamp. All messages had to be on the “face” of the card. That lasted until 1907 when regulations changed once more, giving rise to the familiar divided back–message on the left, address and stamp on the right.

According to rural route carrier and postcard historian, collector, and dealer, John Duda, the first picture postcards were from the 1893 Columbian Exposition held in Chicago. As early as the 1870s, Post Offices sold blank cards with postage printed on them. (The first US postage stamp was issued in 1847). Specific regulations for postcards were passed by Congress and cards during that era had to be marked “Private Mailing Cards.” After 1901, cards no longer needed that phrase on them. Unlike cards today, the back of an early card could have nothing more than the recipient’s address and a stamp. All messages had to be on the “face” of the card. That lasted until 1907 when regulations changed once more, giving rise to the familiar divided back–message on the left, address and stamp on the right.

The imaging process evolved over time as well. Very early cards were frequently black and white photos, and often produced by itinerant photographers. They traveled an area taking photos of homes, businesses, sites and sometimes, livestock, negotiating with owners as to price and quantity of cards desired.

Fly Mountain post office, one of the smallest in Ulster County was in Eddyville.

Next, hand-colored images appeared, and finally the ubiquitous photo-cards of today. Paper stock also changed from dull to linen (1930-1945). Linen cards tended to be very brightly colored. Before WWI, many United States postcards were designed here but printed in Germany, as the Germans had the most advanced printing processes and equipment. You will see the name of a German city, or simply “Printed in Germany,” when that is the case.

In the 1920s, the swastika appeared on many cards printed in Germany. It wasn’t until the late 1930s that the National Socialists turned it into a symbol of hate. A big black smudge on the message side was often used to obliterate the symbol, making the card salable.

From their inception in the United States, image postcards featured the important institutions– those affecting the lives of ordinary Americans–among those images were often the communities’ post offices. These offices were much more than just the mail that filtered through them. They were social centers. They represented the information highway of their time. And for a country on the move, as was America then and now, information was and is power.

Dutcher’s Store and Post Office, Oliverea, NY. The area is now served by the Big Indian Post Office on Route 28.

US Postal History & Rates

When Benjamin Franklin became the first US Postmaster General in 1775, he already had helpful experience–in 1737 he had been appointed the Postmaster of Philadelphia by the British Crown. But as head of the new nation’s postal service, he set in motion the foundation of today’s system. Tony Musso lays out Franklin’s impressive orchestration of those early years in his September 12, 2019, Dateline column for the Poughkeepsie Journal titled “How much postage in 1775? Mile markers set the cost.”

The rate system was based on a series of mile markers to note the distance the letter traveled plus the number of sheets of paper it contained. The recipient paid the postage, not the sender because until the letter was delivered, it was difficult to know how far it had traveled. This was later amended to give the sender the choice of paying the postage or having the recipient pay. Now, of course, the sender almost always pays.

The rate system was based on a series of mile markers to note the distance the letter traveled plus the number of sheets of paper it contained. The recipient paid the postage, not the sender because until the letter was delivered, it was difficult to know how far it had traveled. This was later amended to give the sender the choice of paying the postage or having the recipient pay. Now, of course, the sender almost always pays.

Musso explained, “Franklin developed a way to measure mileage by attaching a dowel inside a wagon wheel, and based on the circumference of the wheel a clapper would sound at each mile’s interval with a milepost maker erected.”

Some of these markers have been preserved along “post roads,”and are quite visible, especially in Dutchess County. You can view a slide show of milemarkers by James Spratt titled “The Milestones of Dutchess County” at the Marist College website. It features the existing 28 milestones.

The bumped-out addition on the right side of the building was the Plutarch post office at one time. Initially, Plurarch had been known as Cold Spring Corners, but there was another Cold Spring Corners, so the little crossroads was renamed to satisfy the postal authorities.

Today, the structure is a private residence. It is on the north east corner of the intersection of Van Nostrand, Black Creek, and Plutarch roads. The lettering on the card is done in reverse on the negative, that is why it looks awkward. This card maker did many in the area.

Postal Workers’ Names You Will Recognize

The postal service has provided employment to some names that might surprise you. US Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Harry Truman, entertainers Bing Crosby and Rock Hudson, sports world notables Knute Rockne and Harry Hooper, and men of letters William Faulkner and Noah Webster, all put in time working for the postal system according to the USPS (United States Postal Service) government website.

The postal service has provided employment to some names that might surprise you. US Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Harry Truman, entertainers Bing Crosby and Rock Hudson, sports world notables Knute Rockne and Harry Hooper, and men of letters William Faulkner and Noah Webster, all put in time working for the postal system according to the USPS (United States Postal Service) government website.

The Postal Service Grows

It is not surprising to find individuals of note working for the postal system when you see the number of post office sites and the roster of workers over the early years of the system. In 1790, the United States had 75 post offices. In 1828, there were 29,956 employees located at 7,530 post offices. By 1860, that had swelled to 28,498 sites. Post roads covered ever more miles and ever more modes of transport were designated as postal. In 1823, navigable rivers and canals became “post roads.” Railroads joined the designation in 1862.

It was not until 1855 that you were required to prepay your postage. Most surprisingly, it was as late as 1950 that mail delivery was reduced to once a day. Prior to that, some locations and businesses had delivery twice a day. That explains a postcard in my collection that was sent by mail aboard a trolley from New Paltz to Highland asking the recipient to put the forgetful student’s fountain pen on the 3pm trolley back to New Paltz. It was an exam day.

The Post Office, Gardiner, NY

Canceled Offices

While the system grew and modernized, there were many rural offices closed. Some of the names I have come across on canceled stamps include the resorts at Mohonk Lake–post office there existed from 1882 to 1957, and Minnewaska’s which ran from 1882-1947. Each had its own post office on site and given the number of postcards available on eBay® dating from about 1907, their offices did a landmark business.

Sometimes, the canceled mark is from community names foreign to most of us. Recently, a Pataukunk, NY, cancellation sent me looking for its location. Pataukunk (PO dates 1890-1914) was in the Kerhonkson region off 209 on Route 3. Kerhonkson’s office started in 1852 and continues. Hundreds of other small offices closed including Plutarch, NY’s when its territory was divided and included into the larger New Paltz and Highland districts.

Sometimes, the canceled mark is from community names foreign to most of us. Recently, a Pataukunk, NY, cancellation sent me looking for its location. Pataukunk (PO dates 1890-1914) was in the Kerhonkson region off 209 on Route 3. Kerhonkson’s office started in 1852 and continues. Hundreds of other small offices closed including Plutarch, NY’s when its territory was divided and included into the larger New Paltz and Highland districts.

Other offices almost as impressively long-lived as Kerhonkson’s include the West Park post office, serving the area since 1894, although not in its current location. West Park’s first Post Master was the world-famous naturalist and West Park resident, John Burroughs according to Susan and Karl Wick’s Arcadia Images of America series book, Esopus.

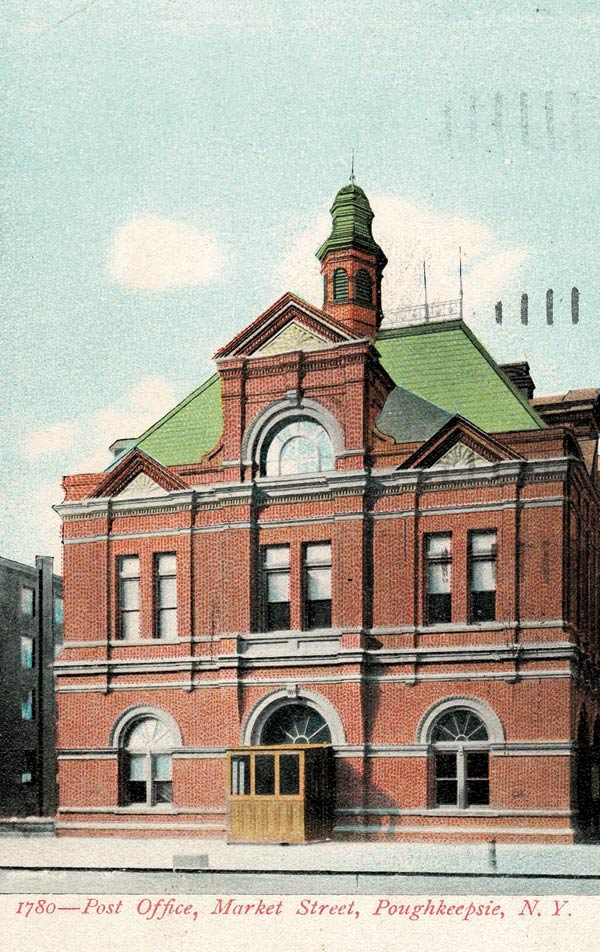

Poughkeepsie Post Office

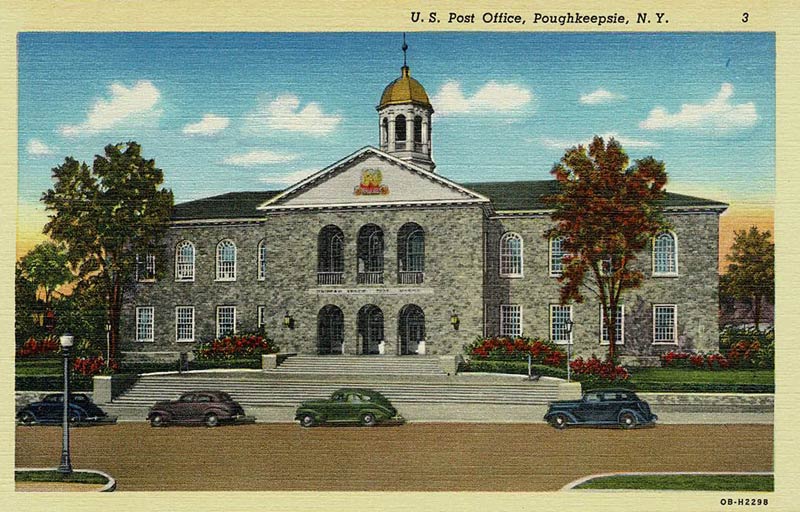

Postcards images below of two Poughkeepsie post offices show one office from the late 1700s and more modern linen card from the late 1940s. President Franklin Roosevelt had a great interest in post office design and was instrumental in many local buildings-especially the post offices of Poughkeepsie and Hyde Park.

1780, Post Office, Market Street, Poughkeepsie, NY

U.S. Post Office, Poughkeepsie, NY

Within many post offices, “New Deal” art was commissioned, consisting of murals and statuary. It was Roosevelt’s way of keeping artists employed during the Great Depression. This art was created between 1935 and 1943. The program was ended by our entrance into WWII. According to the USPS postal history website, “As of 2015, 1,000 post offices house uniquely American Art.” It does not say how much of it was from the New Deal.

Woodrow Wilson’s Postal Dis-service

As with all government actions, there will be individuals who rent-seek or work to snake around the protections of the Constitution. It is one thing for an individual to do so, but when that individual has the power of the government, it is a national tragedy. One shameful time for America and the postal service was Democratic President Woodrow Wilson’s allowance of the re-segregation of the postal service. According to the National Postal Museum website, while running for president in the 1912 election, he promised black voters, “Should I become President of the United States, [Negroes] [sic] may count upon me for absolute fair dealing and for everything by which I could assist in advancing the interests of their race in the United States.”

By April 11, 1913, the move was afoot to do just the opposite. The Postmaster General and Treasury Secretary moved quickly to segregate employees in their departments. Wilson did not stop them. “Many African American employees were downgraded and even fired. Employees who were downgraded were transferred to the dead letter office, where they did not interact with the public. The few African Americans who remained at the main post offices were put to work behind screens, out of customers’ sight.”

Find the full story at the Smithsonian website.