Entry gate of the Snyder House Museum complex showing replica towers and suspension cables of the Brooklyn Bridge, courtesy of the Century House Museum.

Roebling’s Gifts

Fall 2019

Unlike today, fame once equated with substantial achievement—overcoming disease, taming natural barriers, death-defying exploration, tweaking the laws of nature. Fame was once the province of the world-changer.

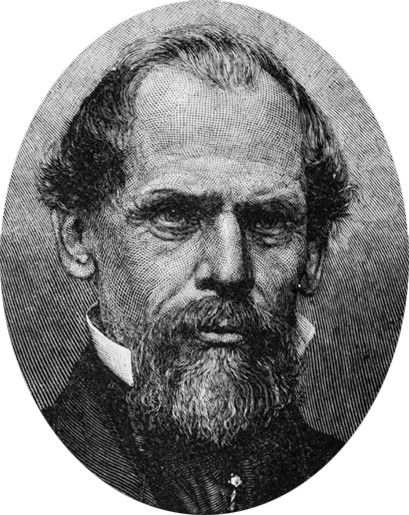

John Agustus Roebling portrait etching from Harper’s Weekly, May 26, 1883.

In that rich vein of past boundary-pushers are many inventors, entrepreneurs and scientists who saw better ways of answering the needs of their fellow humans. Henry Ford, Jonas Salk, and Thomas Edison are all familiar to us. A name that may not jump to the top of mind is John Agustus Roebling. Roebling was an inventor, surveyor, civil engineer, entrepreneur, and designer of such structures as the Brooklyn, Cincinnati, and Niagara Falls suspension bridges. His cable and wire manufactory supplied many projects during the Industrial Revolution and beyond. Similar to his famous wire cables, many substantial strands comprise Roebling’s history and his legacy.

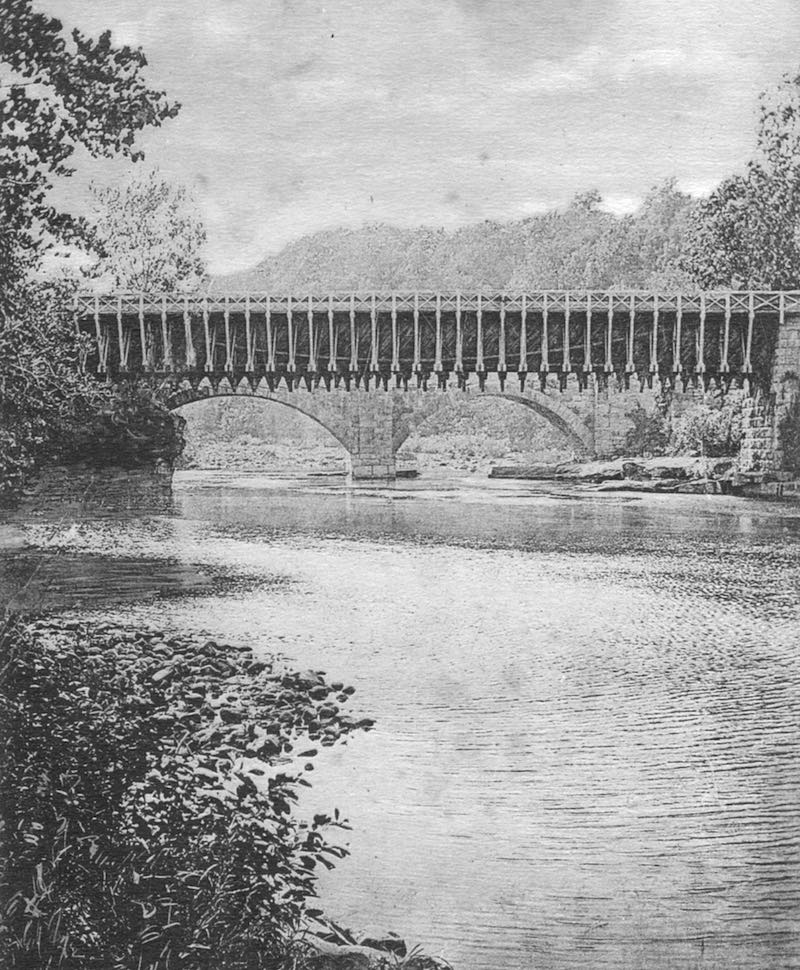

Often, the most memorable aspects of accomplished historic figures such as Roebling come not from their most famous monuments but from the more modest ones that have left familiar traces. Local examples that speak of Roebling’s varied gifts include the entrance gates of the Century House Museum in Rosendale and images of his suspended D&H canal aqueduct. Each cues wonder and memory, giving us a perch to consider a small portion of Roebling’s achievements.

The smallest of these, the Century House Museum gate on Route 213, features lighted miniature replicas of the massive towers of the Brooklyn Bridge. The towers represent the part played by the Snyder family and the Rosendale cement mined by those who lived and worked behind those gates. This natural cement still fortifies the Brooklyn Bridge’s stone towers more than a century later. The swinging gates themselves are metal replicas of the suspension system—the cables invented and manufactured at the Roebling Company for the bridge designed by John Roebling, though he did not live to see the work completed.

Roebling was born in 1806 in Prussia. As a member of a well-educated and privileged family, he studied engineering at the Royal Polytechnic Institute in Berlin and graduated in 1826. For a time, he worked for the Prussian government. In 1831, he left home for America to pursue his interest in designing and building bridges.

And build bridges he did. But before he built bridges, he designed and built suspension aqueducts, including on the Delaware & Hudson Canal (see picture below), and a sprawling manufacturing firm in New Jersey that produced, according to a broadside of the day, “wire rope and wire of every description.” The advertisement listed the users of the company’s products, including, “Mines, Quarries, Passenger and Freight Elevators, Derricks, &c.” Transmission of power over long distances and use on tramways and ferries are among additional listed uses. There was hardly an industry that was not improved using Roebling’s engineering or products.

Detail of a postcard of the John Roebling wire suspension aqueduct in High Falls, NY

Unfortunately, John Roebling did not live to see his greatest bridge rise into the sky. He was injured while surveying for the towers of the Brooklyn Bridge and died in 1869 from lockjaw. Though John was its original architect, it was his son, Washington Roebling, who built the Brooklyn Bridge. When Washington developed ailments suffered from work on the bridge, his wife, Emily, played an important part in bringing the structure to fruition.

The Great Bridge, David McCullough’s fascinating history, is the final word on the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge and all things Roebling. The book opens with a quote by Montgomery Schuyler that appeared in the May 24, 1883 issue of Harper’s Weekly and sums up Roebling’s work:

“It so happens that the work which is likely to be our most durable monument, and to convey some knowledge of us to the most remote posterity, is a work of bare utility; not a shrine, not a fortress, not a place, but a bridge.”

A bridge with roots right here.