A 2014 photo of Elverhoj from the Hudson River.

The Elverhoj Art Colony And Its Kindred Spirits

Fall 2016

The frequency of connections among the places and players in Ulster County’s history–from Gomez Mill House’s Dard Hunter to Gustav Stickley and his publication The Craftsman, from the Roycrofters to John Burroughs and Henry Ford,, and from Sticlkey to the Raymond Riordon School, and dozens of other threads criss-crossing our paths, all add to our sense of place and time. This article deals with just a few of those threads.

Beautifying Life: Artistic “Elves” of Ulster County

The September 1914 issue of The Craftsman magazine, publish ed by Gustav Stickley, printed an article about an artists’ colony in Milton, NY, a small community about 80 miles north of New York City. It was not the first story in The Craftsman relating to Ulster County, nor would it be the last.

But it was the first story in The Craftsman about a colony called Elverhoj. Elverhoj, (pronounced el-ver-hoy) is the name of a beloved Danish fairytale and the first Danish national play premiered in 1828 for the royal family. It translates to “hill of elves.” The Craftsman article, by Hanna Astrup Larsen, described this colony as “…one of the youngest artist colonies in the country… where a group of earnest workers are striving to develop an American school of decorative art.”

Larsen sketched out the founders, Johannes Morten and Anders H. Andersen, as bringing the best artistic traditions of their Danish birth land to the project. Both men were painters and silversmiths who believed it was the duty of every artist to beautify “…the surroundings of everyday life.” The colony motto was “To live close to nature for inspiration.” A similar philosophy guided Hudson Valley naturalist and writer John Burroughs, who penned this quote on display today next to his famed cabin, Slabsides, in Esopus, NY: “If I were to name the three most precious resources of life, I should say books, friends, and nature; and the greatest of these at least the most constant and always at hand is nature.”

Dard Hunter logo for Elverhoj used on the colony’s stationery

Great technological changes were taking place in the world removing vast numbers of people from daily contact with and reliance on nature. To many it was a great foe to be harnessed and exploited, but to those with fresh eyes, Nature became an intimate friend and teacher to be studied, adored, and emulated. At this time, many kinds of colonies were developing, experimenting in all manner of living arrangements, including religious, communal, socialistic, and ascetic. In addition to Elverhoj, major colonies in New York were Byrdcliffe in Woodstock, Briarcliffe in Ossining, and Roycroft in East Aurora. These colonies were based on the concept of reforming society (i.e. perfecting man), noted Dorothy Shinn’s February 1995 article in the Akron Beacon Journal (Akron, OH).

Shinn wrote: “While each of these communities was established with differing mixes of artistic purity and commercial intent, they could all trace their roots to the Puritan communities of 17th-century New England and such Utopian endeavors of the Shakers, Brook Farm, New Harmony and Oneida. The only difference was that the arts and crafts communes were not founded on religion.”

In his search for inspiration, Anders Anderson found the perfect spot for his colony at Milton-on-Hudson. There he purchased thirty acres and a mansion believed in 1914 to be more than a century and a half old. Hanna Astrup Larsen described Elverhoj in her Craftsman article as situated on a bluff, “The veranda looks out upon a terrace, and beyond it is the broad quiet stream of the Hudson ruffled by the tides that sweep in from the Atlantic.”

Above: Elverhoj pin

Like many of the artist colonies that sprouted in upstate New York in the late 1800 and early 1900s, Elverhoj paid great homage to the master-craftsmen of the bygone era. At a time when mass production was supplying the emerging American middle class with unimagined wealth and conveniences, there was anxiety among the leisure class and artists that “true art” and fine craftsmanship would wither if not nourished through the effect of artistic cross pollination. Artists and craftsmen of all fine and decorative arts were encouraged to mingle, to exchange techniques, to grow, and to offer classes to the up-and-coming artists or would-be-up-and-coming artists.

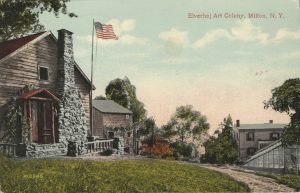

Postcard postmarked 1916. Another with same image reads: “This is view of studio and rear of the main house which fronts the river. Today started sketch, but enjoyed Mr. Scott’s criticism very much. How you would enjoy the exhibition rooms in the house. I believe they have a store in Poughkeepsie. The jewelry was lovely as Miss Raines said. The old homestead of George Innis crowns from a hill commanding a lovely view. Thought you might like to see something of this place sometime in ???. A.B.N.”

Envelope logo for the above–mentioned shop in Poughkeepsie

Larsen described this ideal: “The Elverhoj artists are returning to the spirit of the master craftsmen of olden times, who combined artistic sense with industrial excellence, and who refine their work to the highest point compatible with the retention of the personal touch.” The colony founders believed craftsmen could elevate their production to true “art.” That idea proved to be the hallmark of the Arts and Crafts movement we see today in fine art-pottery, handcrafted furniture, textiles, lighting, and book printing.

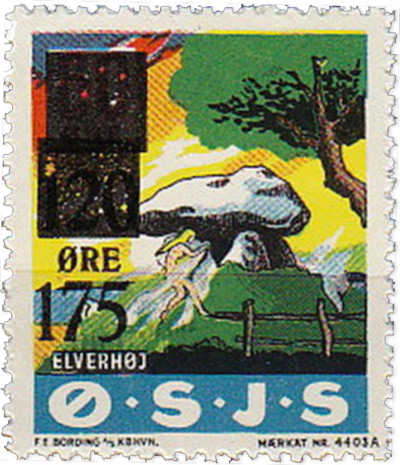

Elverhoj stamp showing a dolman (ancient stone structure consisting of a large cap stone and three pillar stones supporting it) on a hill, and a figure–is it a wood nymph, an elf, a troll, or a fairy?

In addition to fostering sculpture, painting, jewelry design and production, Elverhoj hosted performance artists. Stories about the colony appeared regularly from 1915-1935 in the Kingston Freeman and The Poughkeepsie Eagle (later the Poughkeepsie Journal), as did advertisements for plays and performances, many taking place in theaters at Elverhoj, in Poughkeepsie, and elsewhere. There are more than 400 articles in these rich archives citing Elverhoj and its artists. In addition to the theatrical endeavors, they provided lectures, classes, art exhibits, and concerts. The audiences came primarily from Poughkeepsie, New Paltz, Newburgh, and sometimes New York City. Students who came and stayed for the summer in tents were mostly from North America.

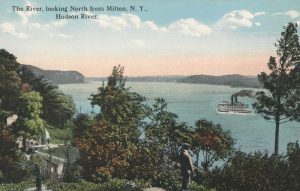

Visitors to Elverhoj could have taken one of the many day boats that plied the Hudson between New York and Albany, and all points in between. Steamship travel was common and would not have been expensive for the social class of people going to Elverhoj for a play, to take a course, or hear a lecture. This postcard image was taken about 1910, just a few years before the art colony was founded. Note well hand-pump at bottom left.

Elverhoj appeared in the press for less glamorous moments as well. Money problems, a drowning, an altercation between a producer and an actress, a robbery…these problems provide insight that human nature has not changed in the last one hundred years. The eventual bankruptcy of the art colony made the estate available and in 1939 the followers of the charismatic black church leader, Father Divine, purchased the site.

His female followers, knows as “Angels” were already ensconced in several other Ulster County large estates, dubbed as “heavens,” including Crum Elbow on the Hudson in Highland. The complete story of Father Divine and his followers is well told in Promised Land by the late Carleton Mabee, a Pulitzer Prize winning author who lived in Gardiner, NY. The photo below shows the “heaven” at Crumb Elbow when occupied by Divine’s followers. Similar to the Shakers, men and women lived separately. The site is today a private residence and most of what is pictured is now gone.

Kindred Spirits of Elverhoj: Hubbard and Stickley

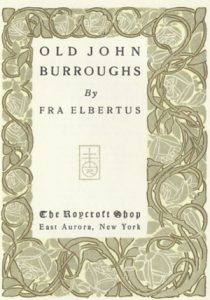

Similar to Morten and Andersen at Elverhoj, Elbert Hubbard also believed in the betterment of humanity though art and culture. Hubbard founded The Roycroft Community in East Aurora, New York, in 1895. Hubbard and his followers produced furniture, leatherwork, and hand-bound books. One such book is Old John Burroughs written by Hubbard under his pen name Fra Elbertus and produced by the Roycroft Shop in 1901. In it, Hubbard speaks fondly of his mentor as he watches the 66-year-old Burroughs tend his cash-crop of celery at Slabsides, “That old Silver-Top out there in the celery has done more than any other living man to inaugurate the love of the Out-of-Doors that is now manifesting itself as a Nature Renaisssance.”

Similar to Morten and Andersen at Elverhoj, Elbert Hubbard also believed in the betterment of humanity though art and culture. Hubbard founded The Roycroft Community in East Aurora, New York, in 1895. Hubbard and his followers produced furniture, leatherwork, and hand-bound books. One such book is Old John Burroughs written by Hubbard under his pen name Fra Elbertus and produced by the Roycroft Shop in 1901. In it, Hubbard speaks fondly of his mentor as he watches the 66-year-old Burroughs tend his cash-crop of celery at Slabsides, “That old Silver-Top out there in the celery has done more than any other living man to inaugurate the love of the Out-of-Doors that is now manifesting itself as a Nature Renaisssance.”

Hubbard’s charming book was printed on handmade paper,. The cover is hand-tooled suede with gold leaf lettering. The book and its content are so lovingly crafted, it is hard to imagine the hours taken to produce it.

Hubbard’s charming book was printed on handmade paper,. The cover is hand-tooled suede with gold leaf lettering. The book and its content are so lovingly crafted, it is hard to imagine the hours taken to produce it.

The thread of Burroughs continued in the fabric of Hubbard’s life, which was cut short by the torpedoing of the SS Lusitania in 1914. Hubbard and his wife were said to have retired to their stateroom room to be together at the end as the ship sank. Felix Shay’s 1926 biography of Hubbard, Elbert Hubbard of East Aurora, contains a foreword by John Burroughs’ dear friend, Henry Ford. Ford wrote, “Elbert Hubbard demonstrated the power of an idea when conceived by an independent mind and supported by intelligent industry. His Shop became a place of pilgrimage to men and women who were interested in the handicrafts and who dreamed of a greater idealization of common life.” Italics added.

Gustav Stickley, a leader and designer of the Arts and Crafts furniture movement, also took the task of education to heart. He published many articles in The Craftsman about options in education. One educator whose work he admired was Raymond Riordon who ran a private boys’ school in the Midwest. Riordon was later hired by Stickley to run a new school he intended to start in New Jersey. Unfortunately, financial circumstances intervened, and Stickley gave up the idea. Riordon, then opened his own boys’ school in 1914 in Highland, NY, and Stickley served on the school’s first Board of Directors. The school closed shortly after Riordon’s death in the mid-1940s.

The Riordon School boys were steeped in John Burroughs’ writing. On burroughs death, as a tribute to him, the teachers and boys planted 4,000 trees and placed a plaque at Rochester Hollow. The plaque reads: John Burroughs Forest. Memorial to the beloved naturalist author, American of Slabsides and the world. Reforested by his neighbors, the boys of the Raymond Riordon School and to be in their perpetual, joyous care under the direction of the the New York State Conservation Commission. April 1921

Vivian & John Wadlin at Rochester Hollow John Burroughs’ memorial ercted by the Raymond Riordon School boys in 1921. Photo August 2016

The kindred spirits of the arts and crafts movement, with their collectives of all descriptions, wanted to propel working people to finer sensibilities through art and work…through the ennobling beauty of nature up close and personal offered by a Burroughs; through the attention, discipline, and pride of handwork offered by a Hubbard and a Stickley; and through the refinement of craft to art offered by an Elverhoj—all spoke of the effort to elevate the hoi polloi and the great unwashed to a better station in life (and in some cases to the hereafter).

The actors and artists of Elverhoj, the artisans and writers of the Roycroft Shop and The Craftsman, the writings of naturalists and other gentle guides from the past have the gratitude of many. Their gifts and the beauty they left fill libraries, museums, homes, and parks, not to mention our hearts and minds.

All images from author’s collection.