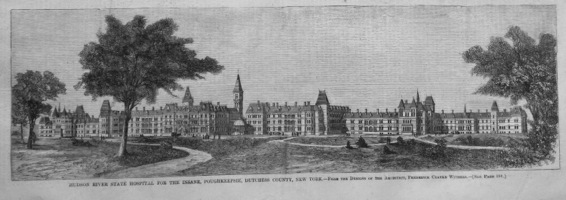

The Hudson River State Hospital 1871–2015

Fall 2015

The Hudson River State Hospital for the Insane, founded by the NYS legislature in 1866, was known through its nearly century and a half to locals by various names including “The Hudson River Psychiatric Hospital,” “Hudson River State Mental Institution,” “Hudson River Psychiatric Center,” “Hudson River State Hospital (HRSH),” and other monikers less publishable, will soon be a memory. To many, perhaps most, a memory fine to forget.

However, to some of us with a personal or family connection, or to others who worked there before the state mandated a different circumstance for residents, there is much nostalgia. Employees often likened it to a village, complete with its own farms, dairy, shoe and clothing factories, golf course, billiard room, greenhouse, churches, staff housing, reading rooms, library, bands, sports teams, power plant, trolley station, nursing school, post office, characters, relationships, and problems.

The original benign mission of these Gothic-structured psychiatric centers of the mid 19th century is the victim of too many modern horror movies. Known as Kirkbride hospitals, their mission has long been forgotten—move the mentally suffering from the stresses of “modern” life into a bucolic setting, give them meaningful work, and let them recover (or at least not be further burdened). Were terrible treatments given to patients? By today’s standards and medical protocols, yes (lobotomy was discontinued in 1957). By historic standards, when the mentally ill were shackled to walls in prisons and poorhouses and given no treatment at all, this system was far more humane.

But the hospital’s story is so much more than its place in the development of psychiatric treatments. Most hospitals built in the mid-1800s for the mentally ill were sited on large tracts of arable land close to large cities. Buffalo, NY, and Danvers State Hospital (MA) among many others, had such institutions and mirrored Hudson River State in many ways. They were based on the “Theory of Moral Treatment” of Dr. Thomas Kirkbride. He saw the physical surroundings of residents as an integral part of their treatment. It was also a time of great public works—often in the Gothic style of building–and a time of epic landscaping.

The spectacular Hudson River site in Poughkeepsie was chosen in 1867. Two years later the architectural firm of Vaux, Withers and Company was hired to design the main building.

Fredrerick Clark Withers had emigrated from England to the United States in 1851 to work for Andrew Jackson Downing (Downing Park in Newburgh was one of his designs). After Downing died in a steamboat accident on the Hudson River, Withers worked with Calvert Vaux (more on Vaux later). Withers’ High Victorian Gothic designs can be seen throughout the Hudson Valley, including several Newburgh and Balmville buildings. Unfortunately, many other buildings designed by Withers have been razed.

Francis Kowsky’s book, The Architecture of Frederick Clark Withers and the Progress of the Gothic Revival in America After 1850, is an excellent source for identifying the buildings Withers designed. The illustration at the top of this page, from an 1871 Harper’s Magazine, is by Withers. Because Kirkbride facilities pioneered the theory of respectful, restful recuperation for residents occupied by productive work, every asylum built to Kirkbride’s specifications had out-buildings for the many occupations and crafts. These smaller structures supported farming, sewing, weaving, spinning, shoemaking, cooking, laundering, grounds maintenance, and a host of other work that residents undertook if they were able. In the buildings housing the patients, Withers included areas called “Ombra spaces,” large, light-filled rooms, on each floor. There was opposition to the structures as designed because of cost. Withers’ original design was almost a half mile from end to end–it ultimately took ten years to build. Structures not directly linked to patient care or work housed the nursing school, heating and water infrastructure, vehicle maintenance, trolley and train stations, post office, and barns. The landscape for HRSH was designed by Fredric Olmstead, most renown for Central Park in New York City.

The siting of the hospital in Dutchess County brought a variety of jobs to the local population on both sides of the river. In researching this article I have spoken with people who worked there (see accompanying story), or whose relatives worked there. Another influence on the mid Hudson region was HRSH school of nursing. It initially trained men and women in the care of the mentally ill but later offered general nursing degrees. The graduates continue to participate in regular reunions.

The fine transportation system in the early days bringing visitors and employees included Hudson River Dayline, railroad, and trolley. Opening the Mid Hudson Bridge in 1930 made HRSH more accessible to Ulster County employees. Prior to that, a small trolley car ran between the east and west shore on the Poughkeepsie Rail Road Bridge (completed in 1888) and provided Ulster workers connection to the site.

According to recent news reports and the new owner’s website, after a 14 million dollar cleanup, the site is to become home to 750 families who will enjoy the 156 acres, sharing it with some commercial development possibly including a hotel. Of the 59 original buildings, only three to five, including the original administration hall will escape the wrecking ball. As an example of Gothic architecture, the administration building was listed on the National Register of Historic Landmarks in 1989. The building’s registration file with the US Department of Interior Register of Historic Places contains this description:

“The most distinguishing feature of the main building is the polychromatic exterior finish. Materials of differing colors and textures were juxtaposed, creating decorative bands, highlighting corners, arches and arcades. Ornamental pressed bricks and stone were also used to decorate wall surfaces. Straight-headed openings were used in addition to traditional Gothic (pointed-arch) windows and doors. Small granite columns support the arched porch that leads to the entrance of the building. The capitals of the columns are of Corinthian order, with small volutes called caulicoli. The entablature enrichments and moldings include dentils along the projecting cornice. The wings of the building have many pyramidal roofs.”

HRSH’s remarkable landscape plan for the original 206 acres, by Olmsted, Vaux and Company, included gardens, walking paths, specimen trees, sprawling lawns, and sporting fields. At the height of the hospital’s occupation, it covered 752 acres. Buildings continued to be added as treatments changed or as technologies improved. Nearby, in Staatsburg, is another Vaux creation, The Hoyt House and its landscaping. Hoyt House is in the English Picturesque style. The building and site are currently under restoration by the Calvert Vaux Preservation Alliance.

Construction of the Poughkeepsie psychiatric center began in 1868 with the first three sections of the Gothic building Withers had designed. It was not until 1886 that the first seven patients were admitted. Three years later, the School of Nursing opened. Before the school closed in December, 1977, it had trained 1,068 male and female nurses, some of whom continued on at the facility. Many worked in other Ulster and Dutchess County hospitals and medical offices.

Other buildings were added beginning in 1891, eventually including a unit in 1955 for patients who also suffered from TB. By 1955 the population topped 6,000 patients.

After 1955, things began to change inside the HRSH and in the larger world of mental health. Insulin therapy and lobotomy procedures were discontinued and by 1960, 90 % of the wards were unlocked. In 1994 the HRSH was consolidated with the Harlem Valley Psychiatric Center. Then in 2001, the lower campus of the Dutchess hospital was closed. The new model for mental health—group homes, psychotropic drugs—were formed integrating residents into the surrounding communities.

It was however, not the last gasp of the site. A new crisis residence, Alliance House, opened in 2003.

HSH Historical Museum

Nineteen-eighty-two saw the establishment of the HRSH Historical Museum. It was relocated and rededicated in May of 2004. Saving the history of these facilities and those who inhabited them is an important chapter in our evolving humanity. It also records the effects of expanded use of psychotropic drugs and newer therapies.

The Hudson River State Hospital Museum on Cheney Drive in Poughkeepsie, is a fascinating storehouse of the history of lives that were often hidden away, but deserving of our attention. From the hand-crafted items made by residents, to the photos and mementos of staff and residents alike, it makes human the alien world of those Gothic towers. Perhaps the most telling object is erected on the museum’s lawn. It is a bell cast from the shackles that once confined the insane to lives of abject misery. We can only vaguely glimpse the change that took place in those lives in 1870s with the “new” understanding of mental illness. Museum tours can be arranged by calling 845-471-2765. Details at www.hrshnursesalumni.wordpress.com. It is a surprisingly upbeat little museum, jam packed with information. It covers fairly the history of the institution and the of evolution of treatments.

Suitcase Exhibit

Several years ago a museum in Albany exhibited artifacts found when another grand psychiatric hospital was razed. The people clearing an attic noted a large number of suitcases untouched for decades. The valises belonged to former residents and contained the minutia of lives long gone, but still capable of communicating a great deal to us. It was a moving exhibit taking bits not only from the residents’ experiences, but also their often devoted caretakers. Many residents, committed as older children or young adults, went to live with the families of staff members who had taken care of them at the institution before it closed. A memorable time capsule well-presented.