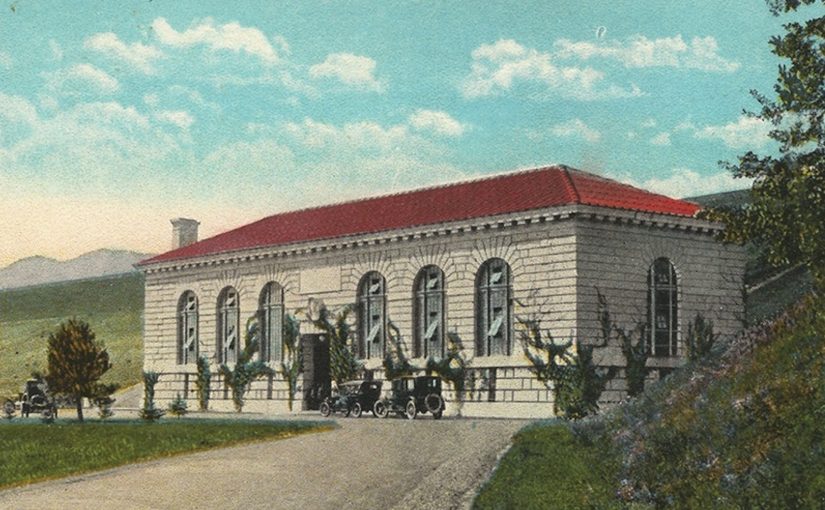

Ashokan powerhouse, image circa 1930

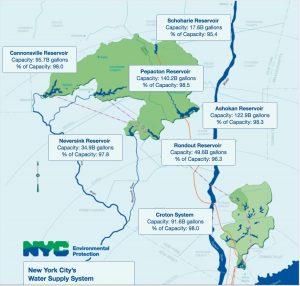

The System

Summer 2016

Turning On the $pigot

On Friday, May 20, 2016, the New York City Water Board voted to raise the cost of water and sewer services for its users. According to a Wall Street Journal article printed the next day, titled “City Water Rates Going Up,” the rate would increase 2.1% effective July 1st. Since 1980 the combined water and sewer rate increased from $.50 per 100 cubic feet of water (748 gallons) to just under $4 per 100 cubic feet of water at the new rate. The sewer component of that price is 159% of the actual water rate. The water is inexpensive. Getting it to NYC was not.

Parts of this huge water system’s distribution infrastructure is under repair or in need of repair. This impacts Ulster and the surrounding counties in many ways, some indirect (land use issues) and some more direct. For example, the Village of New Paltz, which takes its water from the Catskill Aqueduct, is now desperately searching for an alternative source of water while its portion of the aqueduct undergoes much-needed repairs starting in 2017.

Many users of the NYC water system are unaware of its history and current state. Like many quietly reliable things in life, we ignore and take for granted the clean delicious water that has flowed from this system for over 100 years.

Water Rights and Wrongs

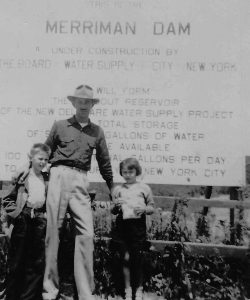

I first became aware of the New York City (NYC) water system in the early 1950s when my father was employed by a company working on the Merriman Dam forming the Rondout Reservoir on the Rondout Creek near Grahamsville, NY. As a child, it was the huge equipment and workers that occupied my interest. Later in life, when I learned about the excavation and construction of the dams, bridges, vertical shafts, and tunnels of the water supply–the enormity of it– the bold imagination and the masterful engineering of the entire system came into focus. Even then, it was only after acquiring Diane Galusha’s definitive book, Liquid Assets, that the rest of the system’s history made it all the more amazing, poignant, and as refreshing as a cold glass of clean water.

At the Merriman Dam. Lou Yess with his children, Lou and Vivian. Photo from around 1951.

Dr. Charles Merguerian of the Hofstra University Geology Department put the NYC’s water system in perspective in a lecture at the Long Island Geologists Dinner Meeting in 2000 with these statistics: “Today’s NYC water needs surpass 1,350,000,000 gpd (gallons per day) for a total of 8,000,000 residents (and their pets, including fish!). In addition, over 100,000,000 gpd are supplied by the system for an additional 1,000,000 customers in Westchester, Putnam, Ulster, and Orange Counties.”

Most of those millions of people in NYC and those along the 92 mile aqueduct from upstate New York reservoirs to New York City know little about the source of their water. They have missed the engaging story of its construction, the lives uprooted, and the bitterness engendered to bring that sweet water to them. And, it is indeed sweet water, kept so by the vigilant protection of the system. NYC has been spared building a water filtration infrastructure that burdened other large cities. Several years ago it was estimated that it would cost four billion dollars to make a purification system capable of providing clean safe water for the NYC metropolitan area. Instead, the Department of Environmental Preservation (DEP) is charged with keeping development in the watershed to a minimum–often to the howls of local governments and landowners. In defense of the agency, the DEP has helped many homeowners’ and towns’ finance the upgrade of their sewer systems, which otherwise might infiltrate the reservoirs. The DEP has also purchased development rights and executed outright purchases of land surrounding the watershed.

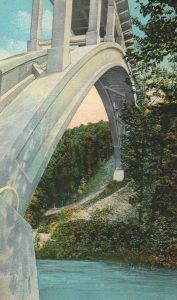

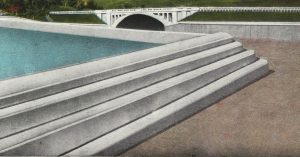

Ashokan Reservoir Traver Hollow Bridge, image circa 1930

The story of this amazing water source started eons ago when the area now supplying water to the city became a well-developed dissected plateau. Once a flat surface, the plateau was eroded by many natural forces including uplifts, glaciers, weathering, and flowing water in the form of streams and rivers. These forces formed the Catskill Mountains and set the stage for a huge watershed, the potential of which only beavers and men could appreciate.

The Catskill aqueduct was initiated in 1907, and it would ultimately cost $177 million in the currency of the time by its completion in 1924. But the thirst downstate continued to grow and after World War II, more water sequestration was undertaken with additional dams, shafts, and tunnels, and more disquiet among the upstaters whose lives were disrupted by the needs of a far-away city that used government fiat to prevail.

Though completed in 1954, the Merriman Dam was a latecomer to the water supply dam construction. Merriman was started in 1937, and completed in 1954. It holds back 50 BILLION gallons of water with a watershed covering almost a hundred square miles. In addition to its own water catchment area, a series of tunnels using just gravity, brings water from the reservoirs at Cannonsville, Neversink and Papacton (Downsville dam). The latter supplies nearly a quarter of New York City’s drinking water. For an idea of the volume of water the system supplies, its reservoirs can contain more than 550 billion gallons: Schoharie holds 17 billion, Ashokan 122 billion, Croton 91 billion, Cannonsville 96 billion, and Neversink 35 billion. Several other smaller reservoirs hold the remainder.

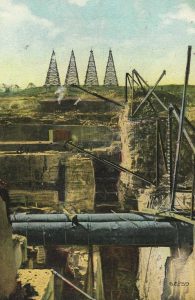

Construction of the Ashokan postcard, postmarked 1908

In the construction of the Rondout Reservoir, the villages of Lackawack, Montela and Eureka were razed and the inhabitants moved elsewhere, their property taken through eminent domain. For the Downsville dam and Papacton reservoir project, completed in 1955, 97 people in several hamlets (including Arena, Shavertown, and Papacton) were removed. Other dam and reservoir construction projects took rail lines, roads, churches, cemeteries, additional villages, farms, and businesses. The deep-rooted anger of those uprooted is chronicled in many old newspapers, monographs, and in books such as Liquid Assets. Those citizens were not the only ones opposed to the reservoir system. Others, who did not want their businesses’ or their counties’ futures hobbled by NYC’s needs and its control, spoke up at public hearings. Samuel Coykendall, a powerful industrialist and entrepreneur in the Hudson Valley, spoke against it at a hearing in Kingston as did many others. Coykendall did not carry the day.

New York City dwellers–and pet goldfish–count your blessings.

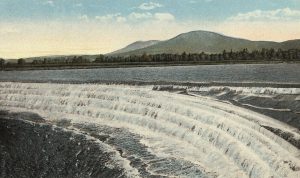

Spillway of Ashokan Reservoir

Ashokan Reservoir Spillway, image circa 1930

Water Aeration at Ashokan

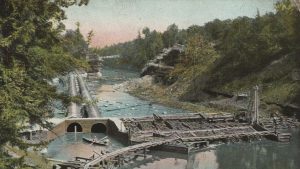

Coffer dam under construction, Olive Bridge, image circa 1908

The Esopus Creek

McClellan Monument on Winchall Hill

2014 photo of the Ashokan Reservoir as seen from High Point Mountain in the Catskills. Courtesy of John Wadlin

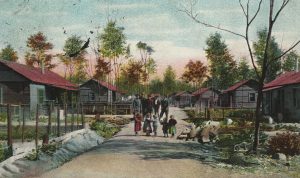

Street scene and workng Men’s Quarters, in the Ashokan District, Browns Station in the Catakills, N.Y., Site of N.Y. City Water Supply

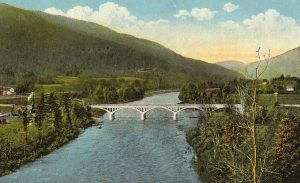

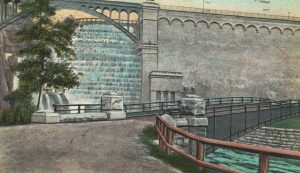

Croton Dam spillway

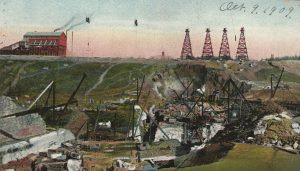

1909 postcard: “The Four Great Draw Towers at work in the Main Dam of the N.Y. City Water Supply, Brown’s Station, in the Catskills”

Images for this story are from the collection of Vivian Yess Wadlin