Walter Williams, Host and Historian

Fall 2007

Introduction by Marianne Williams

History, for my husband, Walter Williams, was not just a subject to be studied in school. It was, for him, a way of connecting with all that had gone before him and passing it along to those who would come after. Williams Lake Hotel was his business but it was also his home. And its history, and the history of Rosendale, became his story as well, a story he learned during his many years here and a story he eagerly passed on to anyone who was interested.

History, for my husband, Walter Williams, was not just a subject to be studied in school. It was, for him, a way of connecting with all that had gone before him and passing it along to those who would come after. Williams Lake Hotel was his business but it was also his home. And its history, and the history of Rosendale, became his story as well, a story he learned during his many years here and a story he eagerly passed on to anyone who was interested.

It was typical of Walter’s enthusiasm that he told this story, not as a dry lecture in a closed room, but as part of a “history hike,” a walking tour of Rosendale’s past. He would leave after breakfast with a group of hotel guests racing to keep up with his long strides and brisk pace. At selected spots he’d stop and tell his story, the story of Rosendale and Rosendale Cement. Each stop would tie an event in history with the place in front of him. In this way Walter lived this history and passed this gift on to countless numbers of guests and friends over the years.

Walter is no longer with us. And his “history hikes” are missed by former guests who wanted to do it “one more time,” and by our newer guests who are fascinated by the mysterious caves and kilns on the property and want to know “what it’s all about.”

Yet Walter would have been the first to say that the history of a place is not the possession of one man. It belongs to all of us. And, fortunately, Walter left behind more than memories. We are lucky enough to have a video recording of an informal talk he gave to some of our guests one late winter evening. This booklet is a transcription of that talk. It is the continuation of the story that was transmitted to Walter and that he, in turn, passed along to us. We know it contains the information but we hope it also conveys the enthusiasm of those many history hikes over those many years. But, please, don’t just read this booklet. Walk out along the trails, past the caves and the kilns, and add your own footsteps to the many that have gone before you. Go for a history hike!

June 1989

Walter Williams Introduction

…I always feel like exploring a little bit when I go to a new place, to find out what the background of the town is, and what’s happened and what is happening. Well, Rosendale has a very fascinating history but I didn’t come to realize it until much later in my tenure here. I first came here in 1928, which is now fifty-eight years ago, as a sonny-boy, and when I came I saw what my father had bought: beautiful lakes, but a wilderness. There was nothing here except the ruins of some industry, which I didn’t realize at the time was cement, but it’s the ruins of a cement industry. So I was told that there used to be a flourishing cement business here in Rosendale, but that it was defunct and no longer in existence and my first thought was that they must have run out of raw material. But that did not prove to be the case.

Right where the hotel is standing there was huge pile of waste material, cement waste material, which was called “slag” or “clinker.” It was about thirty feet high, about two hundred feet wide at the base, and a couple of hundred yards long, the length of two football fields. And our first task here, in trying to make something of this place, was to level this huge pile of cement slag to create a level playground field. And as I looked into the background of the cement ruins that were here I found a most interesting story.

To learn more about the cement industry in Rosendale, visit the Snyder Estate (Century House) on Route 213 through October, open Wed, Sat, Sun 1-4 or by appointment. For more information consult their fascinating website: centuryhouse.org

Stories of Rosendale

Chapter 1: Coal

I’ve got to take you back to a day before the Revolutionary War. This was a farming community and, as in most middle Atlantic and New England farms, farming was very difficult. They tried to plow this rocky soil, nothing like the Great Plains out in the Midwest which had not yet become part of our United States. But these farmers eked out a very difficult living in this rocky soil: mostly dairy farming, and they had various sorts of cattle, pigs, horses, and so on. There was a farmer by the name of Jacob Snyder who had his farm on the banks of the Rondout Creek. That’s at the foot of the hill, you go to the right, westbound, about three-quarters of a mile. There’s a series of rapids there and Jake Snyder had built a dam cross the Rondout Creek to create a waterfall and at this waterfall he built a water-powered flour mill where he ground his grain into flour. And all the farmers in the neighborhood would bring their grain to Jake to be processed into flour.

After the Revolutionary War, when we had made our peace with England, one of the imports from England was bituminous coal from Liverpool, needed to fuel the furnaces of our growing nation. But when the War of 1812 came along Mother England said “If you’re going to be mad at us again and fight us we’re not going to send you any more coal,” and so the coal supply was cut off. We needed coal desperately and we knew that there was coal in Northeastern Pennsylvania, north of the Poconos. It was a hard coal, anthracite coal, whereas the coal we were getting from England was bituminous coal, or soft coal. But that didn’t make any difference — we needed the coal. But there was no way to get it out. Even though — and this was in the days before the railroads — even though there was a canal-building fever going on in the country, canals being built all over the place, there was no canal up into the coal fields. And there was no navigable stream. The closest stream was the Delaware River and that wasn’t navigable. So it was very difficult to get this coalout of those mountains north of the Poconos by wagon-train.

There were a couple of brothers from Philadelphia by the name of Wurts and they owned a big tract of land up there and they figured, “Well, we’ve got to make some money by selling this coal. How are we going to get it to market? How are we going to get it to New York City?” That was the big problem. They engaged the services of a canal-building engineer by the name of Benjamin Wright. Ben Wright had just finished building the Erie Canal connecting the Hudson River at Albany to Lake Erie at Buffalo. They asked Ben Wright to design a canal route to bring their coal to market. After an exhaustive survey, Ben Wright determined that the best route for his canal would be to start at the mouth of the Rondout Creek, where it empties into the Hudson just about seven miles from here, through Creeklocks, right through the village of Rosendale, right past the bottom of the hill where the highway now stands, and on to High Falls which is the next village to the west. From there the canal route took a long, long southwest passage on a long, flat valley between the Shawangunks on the south and the Catskills on the north, all the way to Port Jervis. At Port Jervis the canal took a northward turn on the east bank of the Delaware River, an awfully long distance to a point, past Barryville, New York, opposite Lackawaxen, Pennsylvania. There the canal crossed the Delaware River on the first suspension bridge built in this country by John Roebling. Then it went on up the Lackawaxen Creek and ended at Honesdale, Pennsylvania, fairly close to the coal fields.

Chapter 2: Canals

In building this canal, cement was needed. Ben Wright, the engineer, had a cement plant up in Syracuse. He had erected this plant to supply cement for the construction of the Erie Canal. Ben Wright’s plan was to make the cement in Syracuse, barge it down the newly-constructed Erie Canal, down the Hudson River, up the Rondout Creek to the end of tidewater, and then bring it to the job-site. The idea was just ideal.

Now one of the most difficult parts in the construction of this new canal was right here in Rosendale. There was such a narrow space between the cliff and the creek that they decided to tackle the toughest part first. And that was right by Jake Snyder’s flour mill. When they blasted out for the canal bed they discovered this natural bed of limestone. And the engineers, curious as they are, tested it and found out that it was a high-grade limestone that would make cement. So why go to Syracuse for the cement when they had it right here? They set up some kilns, which are necessary for the manufacture of cement, and they prevailed upon Jake Snyder to change his flour mill into a cement-grinding mill, which he did. That was the birth of the Rosendale cement industry. All the cement that was needed for the locks, the dams, the retaining walls, the piers of the canal-bridge across the Delaware, and for many other purposes, all of that cement was made right here in Rosendale.

Chapter 3: Cement

The canal was finished, the coal started to flow down to New York, and the Rosendale cement industry had served its initial purpose. The canal people were no longer interested in making cement but Jake Snyder, the farmer, never did go back to grinding flour — he stayed with grinding cement. He was right on the canal, there was a good market for it, and the canal boats could come right to his cement-grinding mill and take it down to New York. And not only did Jake Snyder stay in the cement business, but his neighbors went into the cement business: Judge Lucas Elmendorf, Lawrence, and many others. So the cement business began to boom. And soon it was discovered that, not only was this limestone deposit down in the valley along the Rondout Creek, but it extended on this upper plateau all the way to Kingston: a narrow band of high-grade limestone, about three miles wide and about seven or eight miles long. Soon everybody in this area was in the cement business in one way or another. And after the Civil War the cement business here in Rosendale really began to boom. Here on the top of this plateau we had the Lawrence Cement Company, the Norton Cement Company, the Whiteport Cement Company — everybody was engaged in cement manufacture in one way or another. As a matter of fact, this was the biggest industry in the area, in the whole of Ulster County: the manufacture of cement, centered right here in Rosendale. The character of the town changed immensely. Instead of being a sleepy farming community with horses and wagons, and farmers milking their cows and plowing their fields with a team of horses, it became an industrial town. In the first place we had the canal going right through the heart of it, and in the second place we had this new cement industry. A lot of immigrant labor and new financial and social problems that the town and the area had not been accustomed to experiencing. So the people in this area petitioned the State Legislature, in 1844, to form their own geographical and political entity. That’s when Rosendale came into being as a township. It was carved out of four towns: parts of Marbletown, New Paltz, Esopus, and Ulster were formed into the town of Rosendale — basically where this cement deposit lay.

Through gradual economic evolution, there came into being fourteen huge self-contained mills, all making cement.In its heyday, the industry made four million tons of cement a year. Translated into bags, that’s sixteen millions bags of cement a year, year after year, for almost a century, starting in 1825. The industry died in 1910 and that’s a story in itself.

We lay claim to the use of Rosendale cement in many, many famous public structures. The most famous that we like to point to are the foundations and piers of the Brooklyn Bridge. But, in addition, the base of the Statue of Liberty, the Treasury Building in Washington, the Kensico Dam in the Croton Reservoir system, and a lot of other public works: canal locks, dams — the Ashokan Reservoir dam — were all made with Rosendale cement. In fact, the Brooklyn Bridge Centennial, in 1973, recognized the fact that Rosendale cement was used in that structure and they invited the Town of Rosendale to send two representatives to the centennial celebration. My wife and I were very pleased that Rosendale selected us to go to the centennial celebration and we had a great time!

Chapter 4: Ups and Downs

As I mentioned earlier, when I first came here I thought that the industry had died because there was no more raw material and they had to give it up. But such was not the case. If Rosendale cement were made today there’d be none better in the world for brick and stone masonry, if it’s used in a thin layer. The masons loved it. They would put it on their trowel, turn the trowel upside down, or slice the cement onto a brick and hold the brick upside down. The cement was so adhesive that it wouldn’t slide off and drop to the ground. They loved it. But if Rosendale cement is used in a mass, in concrete, it takes forever to set. It won’t harden fast enough. When skyscrapers began to be built in New York City — and the Flatiron Building was the first, about 1900 — they’d pour a cement floor with Rosendale cement and it would take four to six weeks for that cement to get to full strength before they could go up another floor. But the contractors were in a hurry and didn’t want to wait that long.

Meanwhile, the process of making Portland cement — mixing limestone, clay, shale, magnesium, and other chemical additives — was discovered in England in 1890. When the contractors in this country heard of this new Portland cement which would harden in only 24 hours they all wanted it. So the Rosendale cement industry tried to make Portland cement with this new process but it didn’t work. There’s something inherent in Rosendale limestone which precluded it and, try as they would, they couldn’t make Portland cement out of Rosendale limestone. But there was a limestone deposit discovered in eastern Pennsylvania, near Bethlehem, which was conducive to making Portland cement. And when they started making Portland cement in Pennsylvania they stole the market! All the contractors wanted the new style, fast-setting Portland cement.

Chapter 5: Samuel Coykendall

That’s when Rosendale cement took a back seat. Sales went down and hard times came to the cement industry in Rosendale. The fourteen huge mills recognized the fact that something drastic had to be done. They called a meeting: “Let’s form one large company. We’ll pool our resources and see if we can fight off this new competition.” They all thought it was a splendid idea except the descendants of the original Jacob Snyder. There were two brothers remaining at that time and one of them had a son, Andrew, who was twenty-one years old. They said, “Look, we’ve got a good operation. We’re right on the canal, we have a high-grade cement, we have a flat cave. We have money in the bank and we don’t owe anything to anyone. Who needs you? We’ll go it alone!” The thirteen others formed what was known as the Consolidated Rosendale Cement Company. It was actually put together by a man named Samuel Coykendall, a newly-arrived resident of Ulster County. He was a “robber baron,” a capitalist in the old sense of the word. He saw an opportunity to make a dollar and so he said to the thirteen mill owners, “I’ll form your new corporation. I have money and I have access to money. We’ll get this show on the road. We’ll show these Portland people where to get off. Just deed your properties over to my new corporation in exchange for stock. Let’s get going!” So they all turned their properties over to Samuel Coykendall and his Consolidated Rosendale Cement Company. All except the Snyder brothers. They stayed on the outside.

Samuel Coykendall made a go of the cement industry for a while. He became so powerful in the area that there wasn’t a single person’s life that wasn’t touched by him in one way or another. He bought the Cornell Steamboat Company which took freight up and down the Hudson River. He bought the Ulster & Delaware Railroad which ran from Kingston Point up to Oneonta. He bought the trolley-car system in Kingston. He bought a couple of banks and controlled them. He bought the railroad that ran right past Williams Lake, the Wallkill Valley Railroad. He bought the Hudson River Dayline. He controlled everybody’s life in the county. And all the time he was amassing this huge wealth, he was after the Snyder brothers to sell out to the new Consolidated Rosendale Cement Company but the Snyders said “No! We don’t want to have any part of it!”

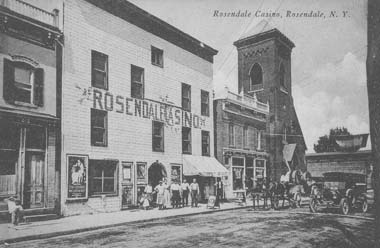

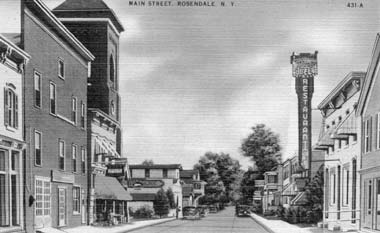

Finally, Coykendall bought the canal. Again he went to the Snyder brothers, “Now will you sell to me?” They still said “No!” “Well,” said Coykendall, “you can’t ship your cement over my canal anymore!” And he put them out of business. It wasn’t long before Coykendall recognized the fact that the Portland cement industry had gotten so big and strong, and had taken such a big share of the market, that he wasn’t paying any dividends anymore from his Consolidated Rosendale Cement Company. So he closed the industry down and walked away from it. Five thousand people out of work and all the other employment opportunities that went with it: blacksmiths, wainwrights, teamsters, grocery stores, saloons (Rosendale’s Main Street was filled with saloons!). It drove them all out of business. Rosendale became a ghost town.

Chapter 6: A.J. Snyder

That’s when the Snyder brothers went back into the cement business, in a crude way. They could market whatever cement they produced but, by this time, they were broke. They had no more money in the bank and the banks wouldn’t lend them any money. But they struggled along. Then, in quick succession, the two brothers died. Andrew, the hero of our story, at that time was twenty-one years of age. He wanted to continue in the cement business in the worst way. But the estate fell into the hands of his Aunt Minnie. Aunt Min was a businesswoman; she knew the cement business. Andrew’s mother was a homebody; she didn’t know anything about the cement business. All she was interested in was putting food on the table and keeping a good house. So Andrew went to Aunt Min and asked if he couldn’t have the cement business. She said, “No! If the Consolidated Rosendale Cement Company couldn’t make a go of it, how can you? It’s a dead industry. We’re going to sell out, pick up our marbles, and go elsewhere.” Well, Aunt Min had a little difficulty in settling the estate and the only way she could solve that problem was to have an auction sale of the property on the courthouse steps. Andrew, by the way, had been given eleven thousand dollars, cash, from his father as a direct inheritance. The day of auction came along but Andrew, being on the outs with Aunt Min, couldn’t go to the auction sale. So he prevailed on a newly-arrived immigrant, by the name of Sandy, to go to the auction sale to see if he could bid on the property. The auction sale started and everyone was surprised to see this stranger in town bidding on this pile of Rosendale cement rock. They thought he was a kook! But when he pulled out a big wad of ten dollar bills from his pocket they realized that they had someone to deal with. The bidding continued and he was the successful bidder. And no one was more upset than Aunt Min when she found out that, indeed, her nephew had bought the property.

So now Andrew was in the cement business. But, true to Aunt Min’s word, the banks wouldn’t lend Andrew a dime. He had to turn to farming to pay the taxes and keep food on the table. And he had a couple of neighbor farmers by the name of Struber to help him out in his crude manufacture of cement. But he had such great faith in Rosendale cement that every year he would send out a brochure to all the cement dealers in the country that he could get on his mailing list, extolling the virtues of Rosendale cement.

Chapter 7: Century Cement

World War I came and went and still no one to help Andrew out financially. But in the mid nineteen-twenties there was a big building boom going on down in Long Island and it was very fashionable to have black masonry joints in the brick veneer and stone veneer homes of Garden City, Forest Hills, Kew Gardens, and similar suburban areas. Andrew could sell all the cement he could make but he just couldn’t make enough of it.

Then one day, in the mid-nineteen-twenties, a cement dealer from Cleveland called Andrew on the phone: “Tell me more about Rosendale cement!” Andrew must have given this fellow a good sales talk because the cement dealer said, “Send me a carload!” Now Andrew was hard pressed to produce a wheelbarrow load, let alone a carload, but he talked this fellow from Cleveland into coming to Rosendale to see what was here. And he was very much impressed. He laughed at the production facility but he saw that it had great potential: a high grade limestone deposit close to the New York City market. He wanted to buy the place from Andrew but one of the secrets of Andrew’s success was that he never sold a thing. If somebody wanted something that he had, he would lease it for a basic lease-hold rent plus a percentage of the profits, or a percentage of the gross receipts. He’d always negotiate a good lease and you had to wake up early in the morning to match wits with Andrew; he was a shrewd Yankee trader.

Andrew gave this cement dealer from Cleveland a long-term lease: ninety-nine years. A basic rent plus so much per bag of cement produced. The cement dealer went back to Cleveland and raised some more venture capital and formed a new corporation called the Century Cement Corporation. They put up a new mill, electrically driven, new silos, new mining machinery, and they started making cement and selling it under the name of Century Cement, “Brooklyn Bridge” brand. It was a great trade-mark and an immediate success. The mill was going night and day and the Ohio people had plans of expanding, building new silos and doubling the size of the mill. Andrew was smiling all the while because with every cement bag that left the mill he got a few cents royalty. He started to become very, very rich.

Then came the Depression. You couldn’t give a bag of cement away. The mill shut down around 1931 and it was idle for a couple of years. The Ohio people failed to pay the rent and Andrew foreclosed on the lease. He got the mill for nothing with no investment of his own! Now he had a cement mill and could make cement, but nobody wanted it. But Andrew had an idea, he was always full of ideas, and this idea led to a new industry for Rosendale.

Chapter 8: Mushrooms

There were a couple of brothers by the name of Knaust who had settled on the banks of the Hudson just north of Saugerties and who were cultivating mushrooms in abandoned Hudson River icehouses. The Hudson River was, at one time, pollution-free and ice-harvesting was a big business. But when the Hudson became polluted and mechanical/electrical refrigeration came on the market, the ice-harvesting business went bankrupt. So here stood these huge icehouses on the banks of the Hudson, empty and idle until the Knaust brothers came along and started raising mushrooms in them. Well, Andrew Snyder went up to the Knaust brothers and said, “I’ve got a thirty-acre cave with a flat floor. Come on down and take a look at it; maybe it’ll be good for your mushroom industry.” They came down and liked what they saw. And that was the birth of the Rosendale mushroom industry.

It became a huge business — beyond the wildest dreams of its founders, the Knaust brothers — to the point where they would harvest five tons of mushrooms every day, day after day. Five tons of mushrooms! They had a mixing plant in Coxsackie, sixty miles north of here, halfway between Rosendale and the racetrack in Saratoga Springs. They had to gather horse manure, topsoil, and straw in a central location and mix it into a compost. They figured that Coxsackie was halfway between the racetrack and Rosendale and there was good farmland up there where they could get topsoil. But the mushroom industry soon became so big that it really wouldn’t have made any difference where they had their mixing plant because, before long, they were buying horse manure from all the race tracks in the country. From Bowie in Maryland, from Santa Anita in California, from the racetracks in New York City and Massachusetts; they brought it in by the carload. They would mix this compost and then load it onto flat wooden trays, about three feet square and eight inches deep, and seed these trays with mushroom spores. These trays would then be loaded on a flatbed trailer, brought sixty miles to Rosendale, and driven right into the cave, just down the road from here. There the trays would be stacked in tiers with an eight-inch brick under each corner so there would be enough space for a picker to reach in and pick the mushrooms out and put them into two-quart baskets. When the baskets were full they dumped the mushrooms into a bushel apple box and when the box was full they’d load it onto a truck, and when the truck was full they’d send it to Hudson, thirty miles from here, where they had a cannery. There, they canned the mushrooms into soup and sold it to the various packers, such as Heinz and Campbells. And if you bought a can of mushroom soup, anytime between 1935 and 1960, you could bet your bottom dollar it came from Rosendale.

They had a rotating crop system: a crop of mushrooms would last about six months and then the fertility of the mushroom spore would be exhausted. They’d have to then dump the exhausted compost onto a waste heap, send the trays back up to Coxsackie to get re-filled, bring back a fresh back of compost and set up for another crop. The rotating crop system meant that in one part of the cave they would be setting up for a new crop, in another part of the cave they’d be picking, and in yet another part of the cave they’d be dumping out the exhausted compost. This went on for a number of years, from 1935 to 1960. In the meantime they were paying good rent to Andrew Snyder for the use of the cave and he was still trying to figure out what to do with his “pet”, the Rosendale cement industry.

Chapter 9: Portland

It’s within our memory, in the early days of cement roads in this country, how the big concrete mixers would lay down a block of cement in the summer heat, followed by a crew of men covering it with straw or hay, and watering it down to keep it cool. It was necessary to keep the cement cool and wet so it wouldn’t set too fast. If it set too fast it wouldn’t set to its full strength. After the winter was over the concrete would be pot-holed, chipped, and scaled on the surface, and this was a problem Andrew was sure he could solve. He conducted experiments mixing a little bit of Rosendale cement with Portland cement and he proved to himself and his small staff of chemists and engineers that he had a superior product for state road construction. But he had difficulty selling this idea to the State of New York Public Works Department until one day when a concrete road was being built between Ireland Corners and New Paltz, about fifteen minutes south of Rosendale. He went to the Public Works Department and said, “Give me a chance to pour a test block using my formula. I won’t get in anybody’s way — the contractor will hardly know I’m there. And I’ll guarantee you that my test block will be superior to the concrete on either side.” So they let him do this and, after the winter was over, he proved the fact that his block of concrete was perfect while the concrete on either side was deteriorating.

From that time on every road built of concrete in New York State had to have one bag of Rosendale cement to every three bags of Portland cement. That was the beginning of Andrew’s meteoric industrial rise and he became a millionaire overnight (this was around 1937). The mill ran night and day. And not only did New York State adopt this formula but other states, even Pennsylvania, the hotbed of the Portland cement industry, adopted the same formula. The arid states of the southwest (such as Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada), where alkali and sand and salt play havoc with cement, all adopted the same formula. After the war was over the New York State Thruway was built: one bag of Rosendale cement for every three bags of Portland cement for its entire five-hundred-mile length from New York City to Buffalo!

The Portland cement people hated to see this small, independent operator from Rosendale make a one-third inroad into their market and they set about coming up with a chemical formula of their own that would match Andrew’s. And it took a long time for them to do it but they eventually did. Especially after Andrew got some big contracts, like furnishing the cement for the concrete for the Eisenhower Locks of the St. Lawrence Seaway, and the bridge abutments of the Verrazano Bridge, and other big public works projects:one bag of Rosendale cement for every three bags of Portland.

So, in 1960, the Portland people came up with a formula that matched Andrew’s.

Chapter 10: Fallout

In 1960, then, two important things happened to Andrew. One was that the mushroom people went bankrupt and went out of the cave and, two, the Portland cement people came up with a new formula that matched his. But Andrew wasn’t one to take this lying down. He was still very energetic even though he was, at this time, approaching “old age.” He said, “I’ll build my own Portland cement plant.” He knew very well the history of Rosendale limestone failing to make Portland cement, but he said, “Where those old-timers couldn’t do it, I’m going to do it!” He built a new Portland cement plant; he set up new kilns, new types of kilns. And when he fired up those kilns everybody within a ten-mile radius knew that Andrew was trying to make Portland cement: the odor was horrible! It smelled like a rotten cabbage-patch. It as terrible; particularly bad on a hot, humid, summer day when there was no wind. We thought we would be driven out of the hotel business. Andrew tried everything to make that kiln work and brought in experts from all over the world. (And this was in the days before air-pollution laws so there was no one to say, “Hold on Andrew, you can’t do this.”) After about three years of sincere, hard work he threw in the sponge. He recognized his obligation to the community: he was annoying his neighbors with the horrible smell. He shut the mill down and lost a lot of money in the process. But he still had a “few bucks” left so it didn’t bother him too much.

Another event occurred in 1960: Castro came on the scene in Cuba at about that time. And we all went through the stage of, “Where are we going to build our bomb-proof shelter? Is it going to be in the cellar, in the back yard, in the garage?” We all went through that trauma. Well, Andrew had an idea that, “By golly, that cave that the mushroom people just left would be a good place to store business records! Atomic-proof, fire-proof, everything you’d want for safety in the event of a disaster.” He sold this idea to some businessmen and they formed what was then called the New York Underground Storage Facility. He leased, with a portion of the gross receipts to go towards the additional lease payment. The original sales pitch was: “Build your alternate business headquarters underground: Atomic-proof and fire-proof.”

In recent times the sales pitch is not so much of an atomic disaster situation but rather as an alternate business headquarters or for the storage of vital business record so that, in case of a fire in an office or factory, there will be back-up records. There are a number of Fortune-500 companies located down in that cave and each one has its own particular function. There is a record-retrieval service, a microfilming service, and a delivery service. There is a New York messenger service going back and forth every day of the week so if some company in New York City wants something out of a particular file, they can pick it out and deliver it.

Chapter 11: Rails…

Another fascinating story is this railroad which at one time was very busy. It was called the Wallkill Valley Railroad and at one time it was destined to become the main line between Canada, Albany, and New York, with the terminus at Hoboken. There was a railroad-building race going on with the Vanderbilts putting together the NewYork Central Railroad on the east side of the Hudson River and the Wallkill Valley Railroad building on the west side, starting from the south. They came to the gorge of the Rondout Creek, here in Rosendale, and had to build a huge bridge, and that’s where the construction stalled. And the Vanderbilt’s won the race to Albany and the New York Central became the main line.

But when I came here with my father, mother, and sister, in 1928, this was a very busy railroad. Commuter traffic from the Wallkill Valley, south of here, found employment in Kingston which was a center of the needle trades: dresses, shirts, and pajamas. Manhattan Shirts were made in Kingston as well as Jonathan Logan fashions and Barclay knitwear, and a silk mill. There was also cigar-making, a small manufacturer of automobiles, and two or three metal foundries. Everyone gravitated to Kingston for employment. The kids even went to high school by train. This railroad carried Railway Express, a mail car, and a milk car. A freight train would come down every morning (at about 10:00 at Binnewater), stopping at every station and unloading lumber, cement and various materials that people would have ordered. The farmers also shipped their eggs to market via Railway Express. But the big money maker for the railroad was anthracite coal from the Pennsylvania coal fields on the way to northern New York, New England, and Canada. Every single day a huge, long trainload of coal cars would come lumbering past.

The trestle over the Rondout gorge in Rosendale has a curve in it and, coming across in this direction, the trains had to go very slowly. They were pulled by two coal-fired locomotives, double-headers, small compared to today’s diesel locomotives. That trestle is also at the bottom of a railroad hill and we’re at the top. It doesn’t look like much of a hill but, in fact, there’s quite an increase in elevation. When those locomotives came to this side of the bridge they had to get up a head of steam, get some speed up, so they could make the hill. Invariably they would stall; the freight train would be so heavy and so long that it would stall. Right opposite the main entrance to the Hotel they’d come to a grinding halt!

There were two ways they could overcome this difficulty. The first way was the easiest but, invariably, it would fail. The brakeman in the caboose would set the brakes and the train would back up, compressing all the couplings. Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang! It made an awful racket! Then, at a given signal, both lead locomotives would go full throttle ahead. The big drive wheels would grind on the rails and the smoke and soot would shoot out of the chimneys. Sparks would fly and the forest would catch on fire. There was a lot of excitement! And as those couplings stretched out there was another big racket. Sometimes they got enough momentum that way to make the hill but usually it failed. In the meantime, our crossing was blocked. To get from one side to the other we had to crawl underneath the cars or else drive down to Binnewater and come back on the other side. It was a little bit of a handicap but, at the same time, it was exciting.

When they couldn’t make it after two tries they tried another method. They’d split the train in half and pull the front half up to the top of the hill, just past the tennis courts and parked it on a siding there. Then they’d back up, pull up the second half, hitch the two halves back together, and head on to Kingston. This was almost a daily occurrence.

Chapter 12: …to Trails

As years went by, one service after another was abandoned. The milk car was taken off, the Railway Express was taken off. The kids went to school by school-bus and the women went to work in the needle trades by bus or in their own cars. The passenger car and the mail car disappeared. And the coal traffic ended when people started using oil heat in their homes. So a time came when the New York Central wanted to get rid of the railroad. They did everything they could, but the various communities on the line had pride in the railroad and didn’t want to see it go out of business. And the red-tape of the Interstate Commerce Commission forced New York Central to keep it going, but they didn’t do any work on the roadbed and it deteriorated. When Penn Central was formed they again tried to abandon the road and, by this time, community interest in the railroad had declined. But there was one manufacturer in Walden, about thirty miles south of here, who had a box factory. He made gift boxes for such department stores as Saks Fifth Avenue and Altman’s. He needed one carload of raw material each week and he insisted on his right to the rail service. But finally Conrail (who had assumed control) convinced him that they could service him by dead-heading a car from the southern end of the line if he would permit them to abandon this northern part. They came to an agreement and the northern part went through abandonment proceedings. Two years ago this spring the railswere taken up.

Two young men with some sophisticated machinery took that railroad apart in no time at all. And, while they were doing it, I had to say to myself, “By golly, in 1878, when that railroad was completed, how many horses and mules, how many men had to do hard, back-breaking work to put that railroad together!” It was absolutely amazing. The rails were taken apart with a heavy piece of steel about ten feet long and three feet wide with a hole in the middle of it. They would jack up one end of the rail and slip it through this hole in the metal so the front part of the rail was underneath and the rear part of the rail was on top. Then they’d hook a small tractor to the piece of metal and pull it backwards. The heavy metal held the ties down but uprooted the rails. Spikes, fish-plates, and all in one fell swoop. They didn’t have to get in there with crowbars to pull the spikes up, this procedure did it all, and did it so fast that you’d have to walk quickly to keep up with it! When they had two or three miles of rail torn up, they’d go back and do the other rail. Then they’d edge the rails off to the side of the roadbed where they lay like great, big, long ribbons. They’d then take the same tractor and put long arms on the front of it and go underneath the ties, picking up a great “armfull” of ties, fifteen or twenty, and cast them off to the side.

The ties were then sorted into three grades. The top grade were steel-banded into bundles and could be sold for about $12.00 each. The second grade would sell for about $8.00 each. And the poorest grade were just left there with the hope that people would come by and take them because, under D.E.C. regulations, they couldn’t be burned or buried. And, sure enough, people did come and pick them up, using them for patios, and retaining walls. The rails were left in long pieces to prevent theft until the time when they could be cut and removed. They had an ingenious crane/boom on a flatbed truck which was preceded by an acetylene torch which burned off the bolts on the fish-plates holding the rails together. They pick up the rail, shake it get rid of the fish-plate, and load it on to the truck for shipment to Trenton, New Jersey, where it was re-cycled.

Copyright © 1997 Williams Lake. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

Williams Lake closed its doors for good this past Summer. Owner Anita Peck had previously put an easement on many acres of sensitive land that includes the caves of an endangered bat species and many historically important cement mining features.

Thanks to all the Williamses for their fine stewardship of this land for so long.

Postcard, Rosendale’s Main Street, 1922.

The 1946 postmark of this William’s Lake postcard is probably at about the date of the actual photo. The diving tower is “center-stage” and the hotel buildings are from before the fire. The Williams family took a slag heap of mine debris, leveled it, and built destination hotel and a thriving business that taught many a local teenager how to work, popularized cross country skiing, and put conservation easement on some lands keeping them forever green.

Postcard, Rosendale Main Street, 1930s.

Toboggan run and beach at Williams Lake, 1946.

Century Cement, 1946.