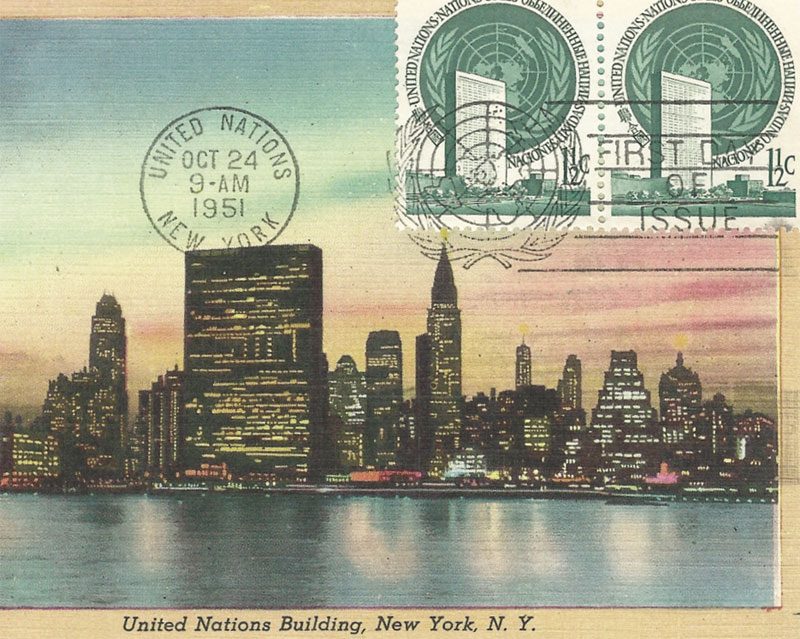

1951 United Nations postcard

What Might Have Been

Summer 2018

Twenty years ago, American Demographics magazine published an article titled “Strong Home Towns.” It was based on a study of the 3,600+ counties in the United States detailing the civic connectedness of citizens in each county and ranking them more or less “strong home towns.” Some of the data they looked at were lengths of residencies, participation in civic groups, church attendance, home ownership, and business ownership. Out of those 3,600+ counties, Ulster had the distinction of being number three, behind Litchfield, CT, and a county in California. This article is about events that would have substantially changed our county and would have in some cases moved us to a much lower ranking in the next strong home town study.

The United Nations Headquarters

On January 9, 1946, a photo appeared in the Kingston Daily Freeman. Its long caption read, “The local UNO Committee mapping a tentative itinerary for the Sub-Committee of the United Nations Organization (UNO) was impressed with the view shown above from Camp Chi-Wan-Do on the River road (sic) between Port Ewen and Ulster Park.”

Next to the photo, an article stated that the American Legion Post of the Town of Esopus had adopted a resolution “pledging the complete support of that organization to make the town the site of the proposed headquarters of the United Nations Organization.”

Just below the photo was a tiny article titled “Would Invite UNO to Locate in State.” The New York State legislature had passed a memorandum resolution inviting the U.N.O. to locate in New York State. It pledged “…full support to help make the living and working conditions of UNO delegates and staff as good as possible.” NYS was not alone, as in total, 248 cities were vying for the UN headquarters.

Actually, New York State had multiple sites under U.N. consideration, as did almost every country in Europe. For a world tired of the death and destruction of war, the concept of nations united was a quest worth pursuing. In addition, wealth would flow to whichever site was selected, as delegates would be living there from around the world and have vast needs for the local economy to supply.

It is difficult to comprehend the explosive growth and changes to rural Ulster County had the United Nations been situated here. The Esopus site under consideration had once part of the huge Robert Livingston Pell farm and estate. The estate was located on the west shore of the Hudson River south of the county seat of Kingston, extending from today’s hamlets of Port Ewen to West Park. Esopus Island, known earlier as Pell Island, is located mid-river about half way between these two hamlets.

The Camp Chi-Wan-Do property, mentioned above, is today a Scenic Hudson park called High Banks Preserve at 132 River Road, Ulster Park, NY. This 287-acre preserve provides three miles of hiking trails, a variety of terrain and habitats, and views of the Hudson River and Esopus Lake.

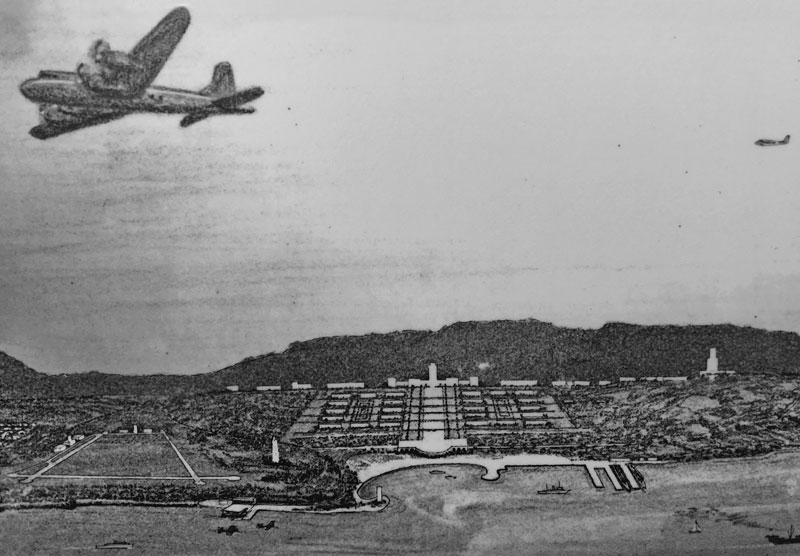

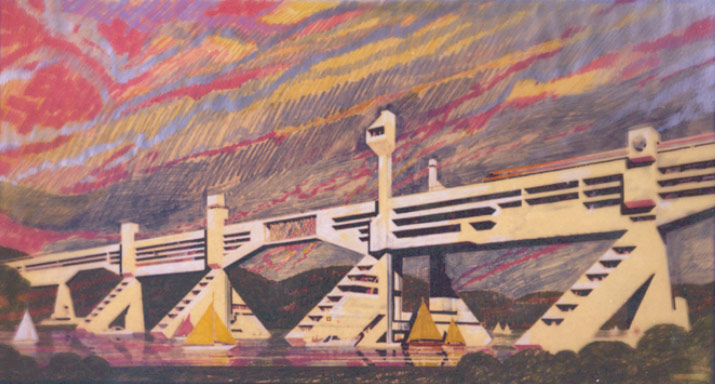

Artist’s concept of the U.N. site for the Town of Esopus on the Hudson River. Klyne Esopus Museum Collection.

Not everyone was so enamored to have this huge influx of people and media. Many property owners, fearing eminent domain, organized to oppose the proposed U.N. headquarters. They needn’t have bothered. Ultimately, the question was resolved with a donation of more than $8 million dollars by John D. Rockefeller, Jr. for 16 acres of land in Manhattan, the home of the U.N. today.

However, even that was not without controversy from every side, including the proposed design of the headquarters. Frank Lloyd Wright said of the design, “It resembles a super crate in which to ship a fiasco to Hell.” Wright’s quote appeared in Script magazine and was reprinted on August 1, 1948 by former U.S. Secretary of the Interior, Harold L. Ickes, in his syndicated column, Man To Man.

Ickes went on to question in his column the propriety of Mr. Rockefeller’s gift and how, because of gift tax manipulation, taxpayers ended up supporting the U.N. land more than was being reported. Ickes wrote: “A conservative estimate is that tax on his gift of $8,500,000 would have been $3,709,440. This then is the sum contributed indirectly, and unconsciously by the taxpayers of the nation.”

Esopus Lake, Fall 2017. Author’s photo.

Today, the United States taxpayer continues to heft the largest share of any nation to support the U.N., not even counting opportunity costs associated with so much valuable land off the New York tax rolls. Regardless, many are just thankful it did not end up in Esopus.

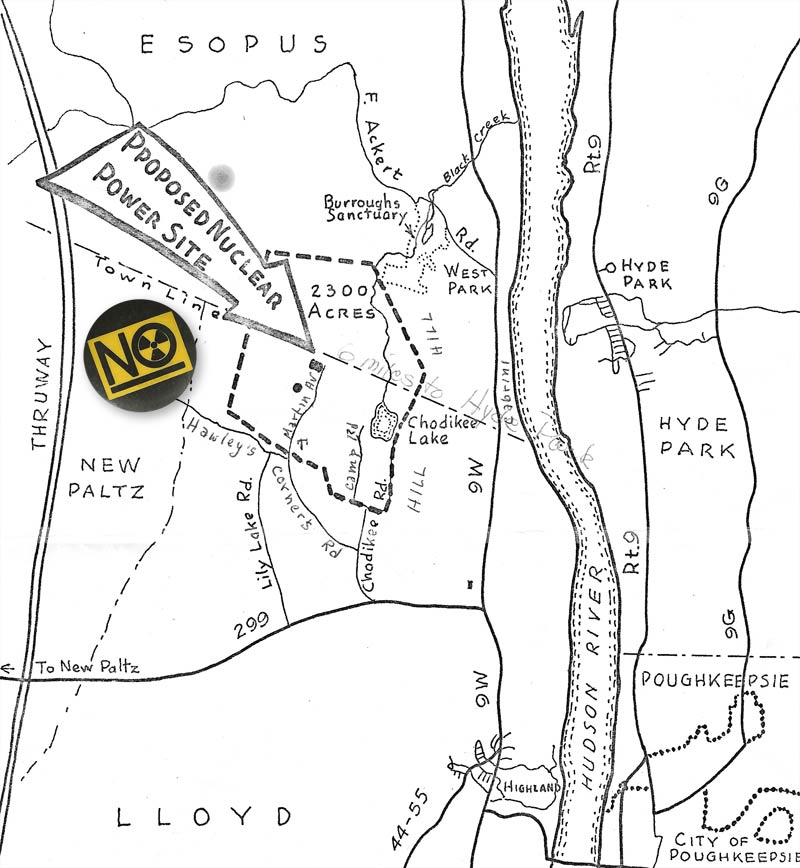

Lloyd Nuclear Power Plant

In the early 1970s, the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (ERDA) completed a two-million-dollar study to determine the suitability of locating from one to four nuclear reactors (and cooling towers) or an oil- or gas-fired generating plant on a 2,300 acre site in the Towns of Lloyd (Highland) and Esopus, NY.

ERDA conducted studies that utility companies could purchase but did not itself construct generating plants. These studies considered a site’s meteorology, geology, terrestrial ecology (flora and fauna), human-population densities, historical value, and other aspects important to safety, as well as to garner governmental permissions for plant construction at particular sites. Any generating facility would have to be approved first by New York State and then by Washington, D.C.

Map of area proposed for from one to four nuculear reactors and a button for the “Nuclear Opponents” (NO) group.

A front-page article in The Mid-Hudson Post (Highland, NY) reported that Consolidated Edison had been in contact with ERDA three months earlier inquiring about the Lloyd site study (“Con Ed Buys Atomic Site Plan to Study,” 17 Nov 1976). The headline was misleading. The article went on to say Con Ed had not purchased the site study nor had other parties who been at the ERDA offices to review it. Since the Lloyd site was one of several under consideration, it would seem that as of 1976 the fate of all the sites was up in the air.

The Lloyd site was actually about 1,400 acres and the Esopus one about 900 acres. Water for cooling would most likely be drawn from the Hudson River. Of the acreage mentioned, only a small fraction would actually be disturbed for the plant construction. The rest would be essentially a buffer zone.

The March 9, 1975 Sunday Times-Herald Record (Middletown, NY) published a map showing the site surrounded by concentric circles extending out 25 miles. These circles illustrated potential impact of evaporation from cooling towers depending on weather conditions. The map’s caption read in part, “Opponents of the Lloyd nuclear power plant say water from the nearby Hudson River necessary to cool giant generating units will produce giant ‘plumes’ of airborne vapors.”

The Record pointed out that the closer one lived to the plant, the more impact would be felt from weather-related conditions caused by the plant. The newspaper noted fog, hail, and humidity as potential impacts. Another newspaper had the estimate at 19 million gallons of water daily per cooling tower. (Four towers were considered for the site.)

This was just one list of dire consequences predicted by various opposing groups. The most consistent objection was the potential for accidents, with ultimate storage of spent nuclear material a close second. On the other hand, one questionnaire by an area politician suggested that a majority of people in the potentially affected area was actually in favor of the plant. This could be explained, at least in part, by newspaper articles suggesting that taxes in towns affected could be 40% lower. Included in this tax windfall was New Paltz because its school system was partly in the 2,300-acre Lloyd site and would benefit along with Lloyd and Esopus residents.

As it turned out, of course, no utility company purchased the studies, although there continued to be interest in the site. A Poughkeepsie Journal headline of July 23, 1976 stated, “A-Plant At Lloyd is ‘Out.’” Staff writer, Jim Detjen, reported, “The Lloyd nuclear site, which the state trumpeted as the possible location of four nuclear power plants only six months ago, has apparently died a quiet death.”

Months after that article appeared, the headline of a December 29, 1976 issue of the Mid-Hudson Post declared, “Sorbello Farm Is In The Way of Power Plant.” Mrs. Mary Sorbello, an owner of a unique black dirt farm, stated she and her husband would be hard-pressed to find another farm with the kind of soil found there. At the end of the interview, she said, “We like it here. It’s peaceful. The only complaint we have is the taxes. They are too darn high.”

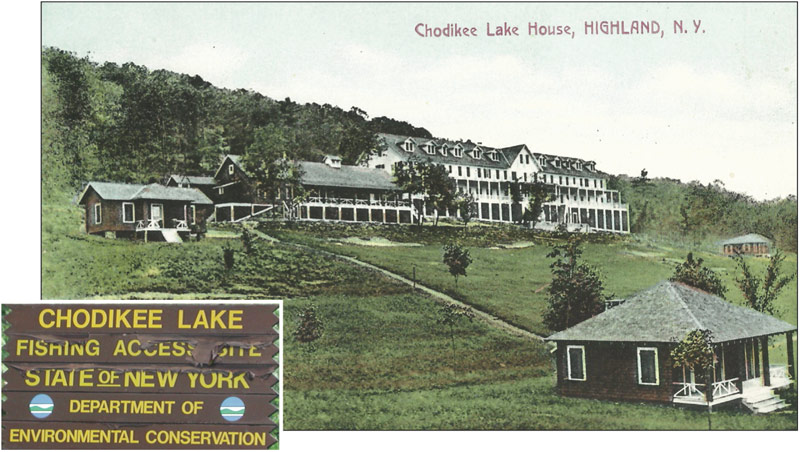

1909 Chodikee Lake postcard showing some of the land that would have been impacted by the propsed nuclear power plant. No original buildings survive. Site in card is today a detention facility for youth surrounded by barbed wire-topped fencing and closed to the public. It can be viewed from the boat launch on the west side of the lake. See insert.

Then, in April 1977 it was said Con Ed was planning to lease 1,000 acres to study the “core area” of the Lloyd-Esopus study site. Newspaper stories notwithstanding, the prospect of a large generating facility seemed to be quite alive. News articles continued to whipsaw the local communities between the death knell of the plant and the plant still being an option. Finally, official word came that the powers-that-be were persuaded the site was not a go. Locals, for the most part, were relieved.

Poughkeepsie Highland Railroad Bridge

In the wake of the May 8, 1974 fire that closed the Poughkeepsie-Highland Railroad Bridge, it was initially reported that the owners, Consolidated Rail Corp (Con Rail), would repair the structure. On examining the potential for using the bridge and profiting from the repairs, they could not justify the expense.

Their next plan for the span was demolition. Bids were sought and ranged from $1.3 million dollars to over $19 million plus the scrap content. The structure weighed in at 31,000 ton of iron and steel. Meanwhile, preservation groups and entrepreneurs were pushing to save the bridge, though for very different dreams.

Edward Loedy’s concept for the Poughkeepsie Highland Railroad bridge after the 1974 fire that closed it. Concept & drawing by Ed Loedy Architect, 1979.

Ultimately, Con Rail sold the bridge for one dollar to a questionable buyer from Pennsylvania. It was alleged the purchaser’s agent had spent some time in prison for misappropriating bank funds. One news report speculated the sale was a sham to relieve Con Rail of the liability for the colossal iron white elephant.

At the time of the sale, an article dated April 28, 1985 in The Daily Independent (Kannapolis, NC) stated that Con Rail was considering dynamiting the bridge. River enthusiasts and shippers were not impressed.

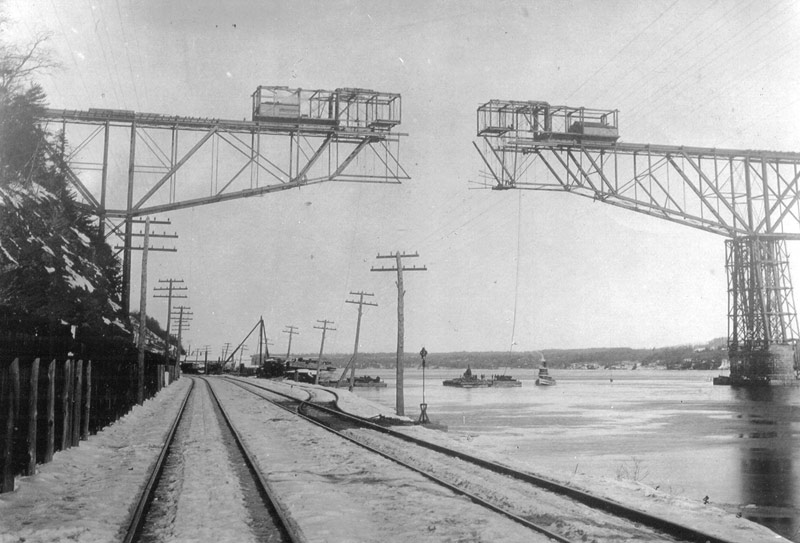

Building the west side of the Poughkeepsie Railroad Bridge in the late 1880s.

The Poughkeepsie-Highland Rail Bridge was completed in January 1889 at a cost of $10 million for the Maybrook Railroad Line of the New Haven Railroad. Its double track allowing two-way traffic was later changed to a single track. The bridge was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. Its importance cannot be underestimated in facilitating the exchange of Pennsylvania coal and New England manufactured goods and as a cog in the national defense network for moving soldiers and goods. It had armed guards during World Wars I and II.

The Poughkeepsie-Highland Rail Bridge was completed in January 1889 at a cost of $10 million for the Maybrook Railroad Line of the New Haven Railroad. Its double track allowing two-way traffic was later changed to a single track. The bridge was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. Its importance cannot be underestimated in facilitating the exchange of Pennsylvania coal and New England manufactured goods and as a cog in the national defense network for moving soldiers and goods. It had armed guards during World Wars I and II.

Local architect Ed Loedy developed one of the most talked about considerations for the bridge. Loedy drew up concept plans to make a linear community with restaurants, observation decks, a bungee jump platform, and housing. He envisioned 6,768 feet of superstructure carrying walkways and possibly a train.

Loedy’s proposal raised many concerns, but the most often heard was the expense to fortify the structure to bear a load of that size and whether the stone piers could bear that added strain. His design was mesmerizing in its futuristic feel. One wonders if Star Wars designers and their ilk didn’t see Loedy’s bridge concept.

A description of Loedy’s proposal appears in Bridging the Hudson, a book by Pulitzer Prize winning author Carleton Mabee.

According to Loedy’s design, the entire bridge was to be strengthened, widened, and enclosed so that its steel structure would no longer be exposed to the weather. Shops, hotels, and restaurants would be built along the length of the bridge. Each of the bridge’s four piers would have sloping condominiums built against them with their windows facing south for sunlight. All the piers would have observation areas with elevators available. The tower over the second pier in from the Poughkeepsie shore was specially planned as a high observation tower.

Since railroad tracks still crossed the bridge at the time of Loedy’s drawing, he planned for trains to run across it. (A streamlined train shows on top of the bridge at the right.) Loedy believed, however, that since ordinary trains crossing the bridge could shake it enough to endanger any buildings on it, the trains would have to be of magnetic levitation design.

Loedy attempted to buy the bridge to bring his idea to fruition. It was not easy to contact the owner. Tax liens were piling up from Ulster and Dutchess Counties, but there was rental income from electric wires crossing the bridge. When that income ceased, the owner did negotiate with Loedy. To no avail.

Shortly after the 1974 fire that closed the bridge Kathryn Paulsen strolls toward the Poughkeepsie side and the west shore shows behind her.

Enter Bill Sepe. Bill lived on the Poughkeepsie side very near the bridge. He had a vision of turning the structure into a linear park, free for all to explore the wonder of the river and the history of its waters and shores. He wanted everyone to have the opportunity for something that had been unsuccessfully sought by many individuals and groups since the bridge was completed–access to walk its mile and a quarter in length 212 feet above the river.

Bill’s tireless efforts to secure title to the bridge and form a group of like-minded workers were the genesis of today’s amazing Walkway Over The Hudson. His dream was achieved, perhaps not by the process he envisioned, but the incredible success of today’s Walkway is nevertheless a great credit to his foresight and determination.

Ultimately, the Walkway that opened in 2009 was underwritten by private and public funds. Much credit goes the volunteers, especially to Fred Schaeffer who led the project through its final and complex hurdles.

Just prior to the renovation to become the Walkway Vivian Wadlin surveys the view with the east shore behind her.