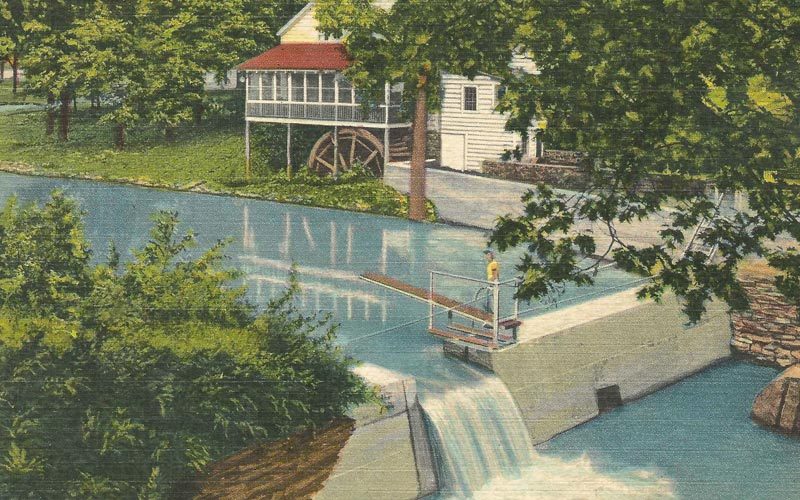

Linen postcard circa 1945, back of card reads: Woodstock, New York. Woodstock Country Club Mill. This was a grist Mill from 1788 to 1925. Also run as a Carding Mill 1836. It is now the Woodstock Country Club.

Woodstock: An Original Long Before…

Spring 2018

Outside influences, large and small, tangible and intangible, have shaped Woodstock, NY, for the last 100 years or more. Ideas that crossed the Atlantic in the prior century challenged the accepted orthodoxy of community. Worldly painters brought the beauty of the wild to the city-bound. The affordable publishing and distribution of newspapers and periodicals helped local businesses reach richer markets. The internal combustion engine made travel and shipping less expensive. The need for fresh water by outsiders changed landscapes and lives. All of these and more shaped the cultural ripples lapping at Woodstock’s borders.

Not all these boulders and pebbles thrown into the mix of what Woodstock is today are that old. So to begin, and to avoid confusion, there is a Town of Woodstock and a hamlet within it named Woodstock. The town consists of other small divisions including Bearsville, Lake Hill, Mt. Tremper, Shady, Willow, Wittenberg, and part of the Zena area. The 1969 Woodstock Festival took place in none of the above.

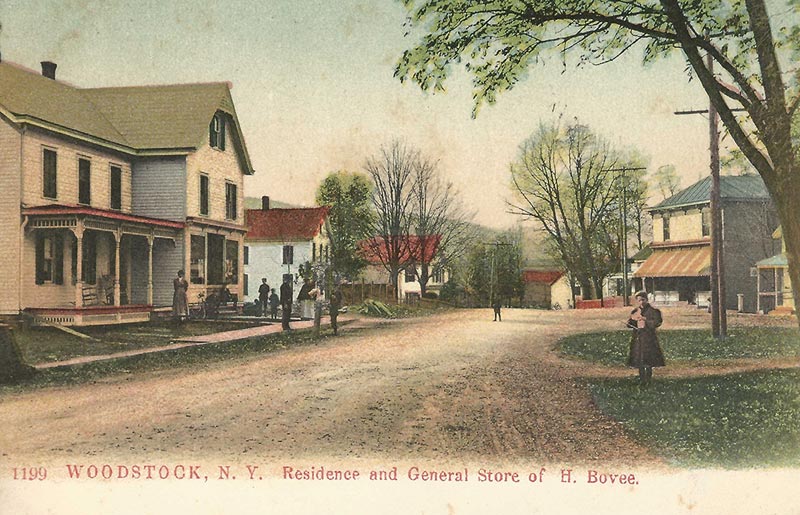

Before the original Woodstock Festival burst into the public lexicon, the real and truly original Woodstock boasted an art colony, a playhouse, a golf course, a race track, a village green, mountain hotels, an art school, concert venues, and so much more. And, before all of them, there was leather tanning, fishing, dirt roads, dry goods stores, grist and saw mills, bluestone quarries, and farms of every stripe–and people with true grit.

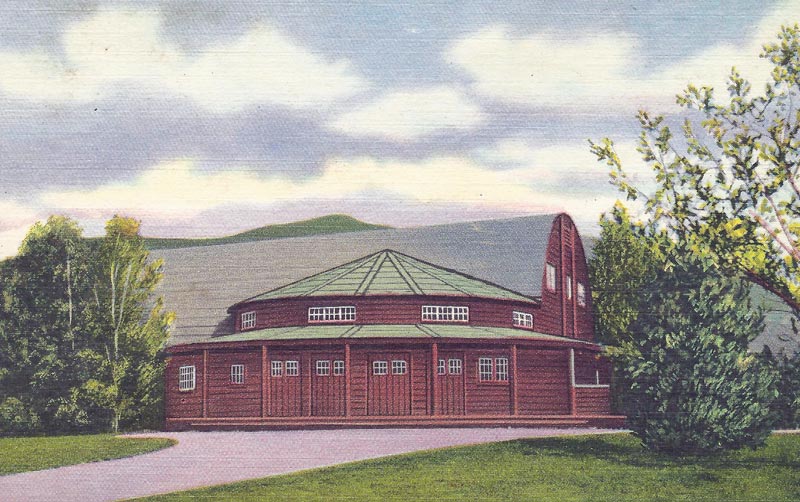

Woodstock, New York. The Woodstock Playhouse is the gathering place for the Theatre goers from many miles around in Summer, and has had many now famous plays introduced in this Theatre.

Woodstock, N.Y. Residence and General Store of H. Bovee. Not postmarked, but from about 1911.

1969, 1994, and Before You Know it, 2019.

Youngsters (those under 55) are forgiven for thinking the 1969 Woodstock Music Festival took place in Woodstock, NY. That was how the festival was misnamed and is remembered. The Sunday Times-Herald Record called it right in its 25th Anniversary edition of the festival on August 14, 1994. The headline that day about the event’s replay read, “Thousands groove on mud and music at Yasgur’s Farm.” It goes on to say the original site was Bethel, NY. Winston Farms in Saugerties, NY, was the site for the ‘94 event.

Among other stories in that issue about these “earth-loving” partiers is the mess they left behind. The Saugerties site was under consideration by the Ulster County Resource Recovery Agency for a landfill. The ‘94 party was billed as saving the site from becoming a dump. Oops. Instead, the estimated 10,000-22,000 person crowd left it a dump. At the time, the good intentions of the promoters were soundly denounced by many local voices as the proverbial “road to hell.”

The landfill landed elsewhere, and you can now visit the real festival site–one sanitized by a very large investment. What had been Max Yasgur’s Sullivan County alfalfa field in Bethel, NY, now houses a museum, a concert venue, restaurants, and shops. The Bethel Woods Center for The Arts provides all there is to know about “Woodstock ‘69”. The Bethel Center is a fitting tribute to the acts, attendees, promoters, and kind-hearted people of Bethel, Saugerties, and Woodstock who took pity on so many of the young and foolish concert goers. In 1969, they fed them, helped them when they were sick, injured or stoned, gave them water, and got their cars out of the mud. And as far as is known, in spite of the festival’s total disruption of traffic, peace and quiet, and sanitation, they did not shoot any of them. Unfortunately, two concertgoers did die, one by farm tractor and the other alleged to have been caused by a drug-induced fall. Not bad considering there were 400,000 unprepareds, boozed and (occasionally) drugged youngsters without adequate food, water, supervision, or porta-potties at the site.

The 50th Anniversary of that event will be here in August of 2019. Grab your love beads, tie-dyes, walker, bifocals, statins, and hearing aids. Relive the joy. Pray for rain.

This, however, is also about some of the other forces that came to bear on the “before Woodstock, Woodstock.” That is Woodstock in the days of plein air artists, musicians, sweet postcard missives, a slower pace, sweltering summer stock, auto races, and vacationers from far afield.

“On old road to Woodstock, Shady, N. Y.” Postcard circa 1910

Woodstock became a town in 1787. It was mainly occupied by farmers and others who subsisted on very hard work that transformed the bounty of mother nature into something edible, wearable, burnable, or tradeable. According to the website WoodstockChamber.com,

“By the 1800s, however, the economic focus of the town began to shift towards more industrial ends. In 1809, in addition to the sawmills and gristmills already operating along Woodstock’s many streams, the first glass factory was built in the hamlet of Shady. By the 1830s, tanning, which required a plentiful water supply and tannic acid obtained from hemlock trees, found both resources in abundant quantities in Woodstock.”

Bluestone quarrying in the surrounding hills and mountains commenced in the late 1800s for sidewalk and building projects in the larger cities. From the booklet “New York State Bluestone,” we learn Woodstock was noted as having delivered a few very large bluestone blocks for building projects and monuments, but soon the large cities wanted bluestone and flagstone sidewalks to get the ladies’ skirts out of the mud and horse manure. The demand for the smaller, more easily quarried and more easily handled slabs brought jobs not just to the miners, but to skilled stone finishers, wagon masters, and shippers.

Bluestone at Rondout awaiting shipment to N.Y. Photo courtesy of Ed Ford and Peter Roberts.

By 1900, the need for water had already changed the area around Woodstock as reservoirs for Kingston, NY, and New York City were built. The huge New York City Reservoir system of five reservoirs flooded out small towns and hamlets and uprooted families who for generations had been the stewards of their land. With all that New York City demanded and took from the area, the proximity of the big city also brought unique benefits to Woodstock.

Communes and Community

Woodstock became a mecca for the arts, often with philosophy leading the way. Byrdcliffe, Ralph Whitehead’s planned utopian colony for artists and craftsmen, began in early 1900. It was and remains a major influence in the town. With his inherited wealth, Whitehead purchased about 1,000 acres in Ulster County where he subsidized his ideal of a collective commune based on the thinking of the English Arts and Crafts movement–romantically based in part on the old guild system of crafts. Whitehead’s socialist ideals were built upon the teachings of John Ruskin (1819-1900), the leading English art critic of the Victorian era, and another Englishman, William Morris (1834-1896), a designer, and manufacturer, also a socialist. (You may thank him for the still popular Morris Chair.)

Many communes, based more or less loosely on English ideas, gave rise to the no-frills American style of furniture, jewelry, and pottery known as Arts and Crafts or Mission style. One of the most influential of the American communes with connections locally was Elbert Hubbard’s Roycroft Campus in East Aurora, NY. Dard Hunter, one of the more famous designers from Roycroft later ran a mill making handmade paper in Marlboro, NY, at what is now the Gomez Mill House. The Elverhoj Art Colony, in Milton, NY, was moved by the same spirit–the desire for everyday utilitarian articles to be handcrafted and beautiful. New ideas, new markets, new wealth, and a laid-back sophistication soaked into Ulster County’s woods, but nowhere more than in Woodstock.

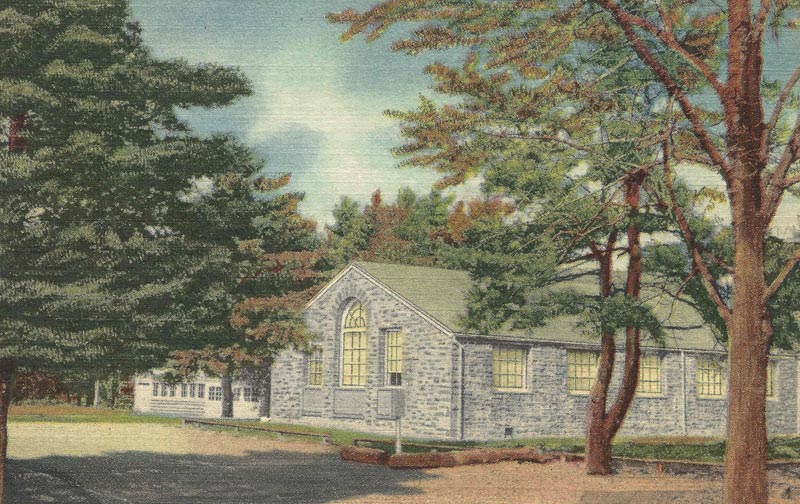

Postcard: “Woodstock, New York. These buildings are the property of the Art Students’ League. This organization located here from 1905 to the middle twenties played an important role in the beginning of Woodstock as an Art Colony.” Postmarked “Woodstock 1955.”

The Art Students League (see image above) and later the Woodstock Artists Association and the Woodstock Craft Guild brought more artists and artisans to the area. Though following in the footsteps of the English philosophical leaders, most of these organizations did not require an adherence to any particular economic religion, but to the goddess of beauty in all things.

Maverick Concerts and the Historical Society of Woodstock added to the ambiance that increasingly brought the rich and famous, and often just the rich, to build their impressive homes–many at Byrdcliffe. In the end, though, it was the rich world of nature that was the biggest draw for the once sleepy village.

Mead’s Mountain House, Woodstock, N.Y.

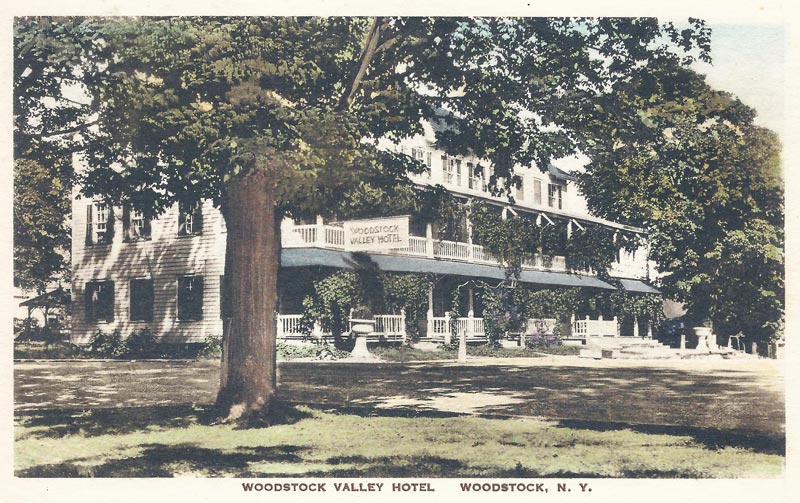

As with their grander cousins–the Catskill Mountain House to the north and the mountain houses of the Shawangunk Mountains to the south–Woodstock’s tourist sites offered rest and relaxation to the city-weary. Mead’s Mountain House and Woodstock Valley Hotel, among others, attracted people who arrived by railroad or steamboats to Kingston, then by rail, and finally by horse and coach to the hotels and boarding houses.

“Woodstock Valley Hotel, Woodstock, NY” Card not postmarked.

One of the many tourist hotels, inns and boarding houses catering to those ready for rest, good food, and fresh air in Ulster County.

As many as 5000 day-trippers disembarked from the steamers in Kingston to spend the day at the Kingston Point amusement park. Once thus introduced to the wonders of Ulster County, the visitors could, as their financial positions improved, aim for a week’s vacation in the countryside.

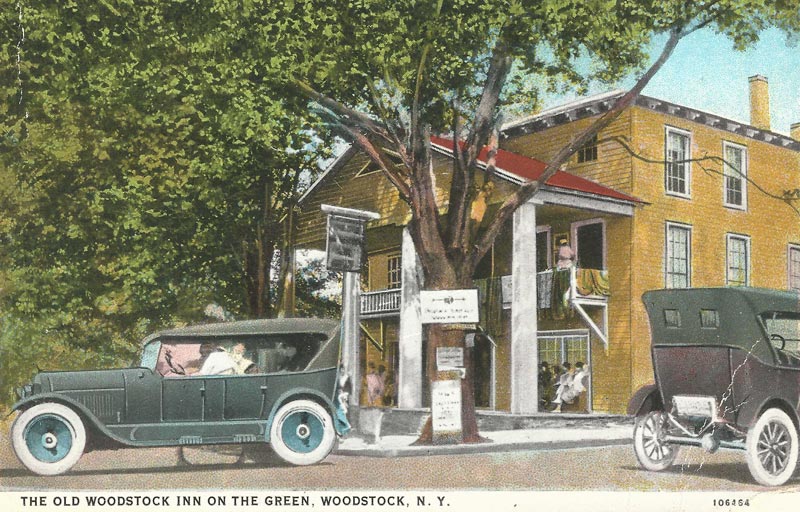

The age of large transportation projects, and soon after, the automobile, dawned. The touring public could go farther afield and the lure of some previously prosperous establishments gave way to the creative destruction of the market. Newer places with more amenities, niftier entertainment, and larger advertising budgets became the expected norm in vacationing. Nature lovers could head by rail to the great parks of The West, or by auto to visit the Adirondacks or the Berkshires. And, of course, Europe beckoned. Many of the older establishments succumbed to these competitive pressures. Boarding houses went back to being farmhouses. Today, with B and Bs and Airbnb, many old homes cycle through again to become base camps for visitors.

The Old Woodstock Inn on the Green, Woodstock, N.Y.

Additional Diversions

A Kingston Daily Freeman headline announced on April 26, 1938: “Woodstock Plans Midget Auto Race.” The opening paragraph read:

A midget auto race is scheduled for May 29 on the Woodstock Legion Speedway. The race track and amphitheater are now being constructed and should be ready in time for the opening races. About 20 entries are expected for which elimination races will select the cars for the opening races.

Woodstock resident, William (Bill) West, a race car driver himself, was a veteran of the Indianapolis, Sheepshead Bay, and Deer Park speedways. He was the spirit behind the Woodstock Legion project. According to the article, West announced the names of those already entered for the qualifying race: John Peper, Gregory Lindin, William West, all of Woodstock; Louis Yess of New Paltz; Jack Franklin of East Hartford, Conn.; and Joe Goldsmith of Ellenville.

According to a later issue of the Freeman, the race track project had formally commenced on May 13, 1938, when its incorporation papers were filed with the Ulster County Clerk. The Speedway had six directors. The stock was 200 shares at $50 par value and the corporation’s offices were in Woodstock. Its purpose was listed as “Entertainment and amusement.” The newspaper article continued with this description of the track’s location, “…operating the miniature automobile speedway at Bearsville or the Lasher property.” Several racing websites indicated there might have been two tracks, one in Woodstock of 1/4 mile and the other in Bearsville of 1/2 mile.

Consulting former Ulster County Legislator Bill West (son of Speedway Bill), I learned the track was on Race Track Road, off Cooper Lake Road in Bearsville. There is no indication of its existence there now, he said. The track was a 1/4 mile.

Races were to be held at the speedway over the Memorial Day holiday season with a preview the week before. “2000 Attend Preview of Midget Races at Woodstock. Speedway,” the Freeman declared on May 23, 1938.

That Sunday the eager crowd, hailing mostly from New York and New Jersey, came to see the drivers race their small vehicles around the quarter-mile track. Spectators were promised that “next Sunday more than 20 midget auto drivers will inaugurate the Catskill Park. ‘The sport that thrills millions.’” In this case, the most to ever view a Woodstock Speedway event was reportedly 7,500.

Then abruptly, the outside world again made its way to Woodstock and the speedway took its final checkered flag. Historian Rik Rydant of High Falls noted, “The last racing season was the summer of 1941. With the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, all racing stopped in the U.S. because of the need for gas, rubber, etc. to help win the war. The Woodstock Legion Speedway in Bearsville never reopened after the war. The Speedway had been sponsored by and named by the American Legion Post in Woodstock.”

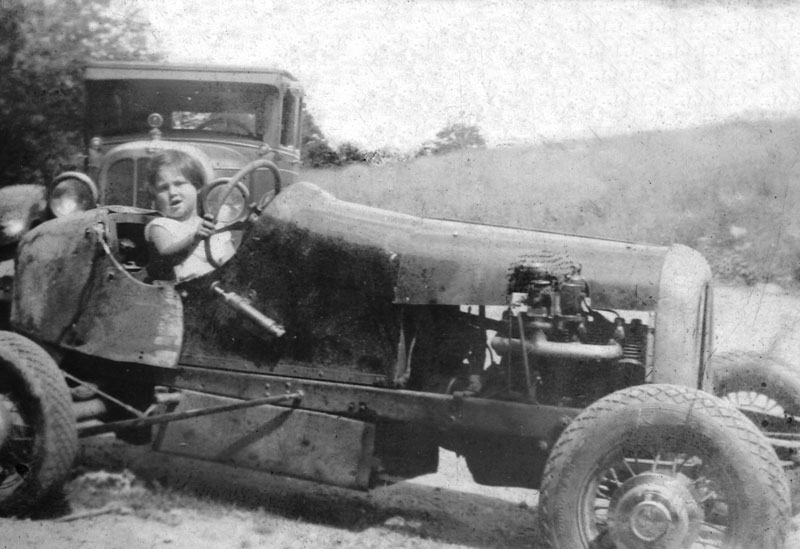

Maryanne Pishkur, niece of Louis Yess, seated in his image from 1938 family album.

Casting More Than a Spell

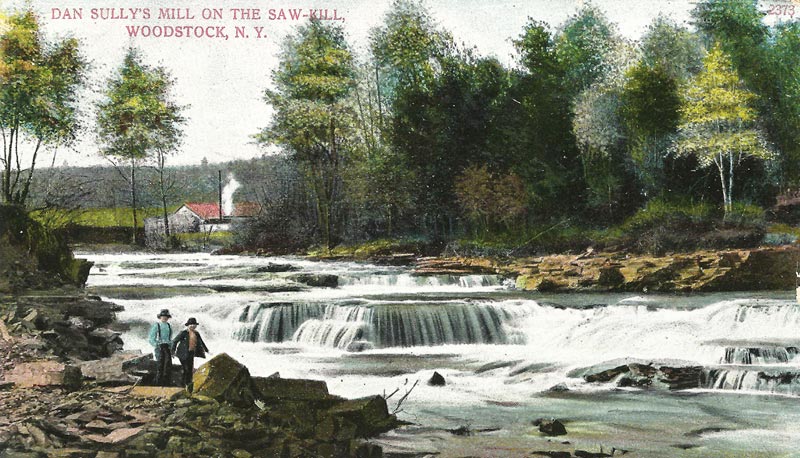

Another major draw to the area around Town of Woodstock that has not lost its allure, or lure in this case, is trout fishing. A noted trout stream is the Esopus Creek. Internationally respected as an anglers’ paradise, it draws some of the most famous fly-casters from all over the world. It helps that the Esopus and other Ulster waterways are now regularly stocked. The Esopus received 20,000 brown trout and the Sawkill Creek that runs through Woodstock got 2,000 browns in April and May of 2017, according to the NYS Department of Environmental Conservation.

Postcard: “Dan Sully’s Mill on the Saw-Kill, Woodstock, N.Y.” Sent August, 1908

The change in Woodstock’s scenery brought by the influx of strangers had its amusing side for the locals. For the resident Woodstockian, it was great fun to “alien watch” even before 1969. The outsiders who have come in droves for theater and music and for the mountains and nature, who have clogged the village green and spent money, make Woodstock evermore an interesting tourist destination.

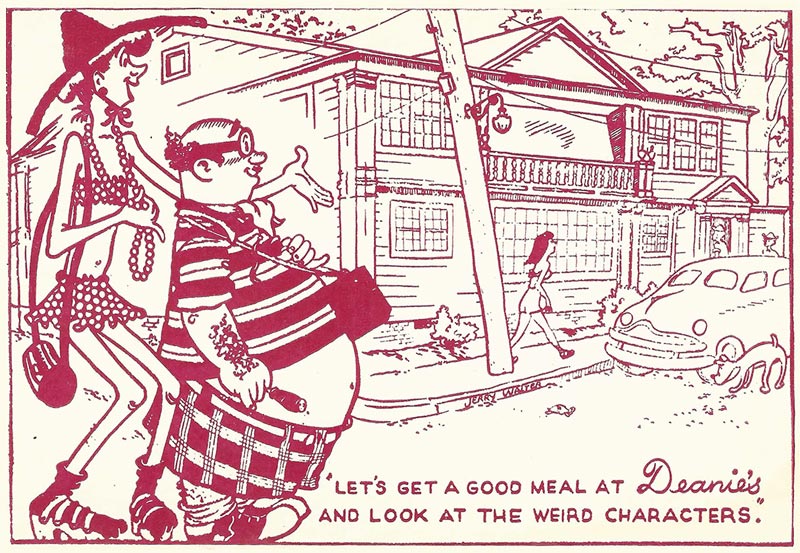

Shops accommodating the wants and needs of these newcomers drew on the marketing techniques of more sophisticated concerns, often because the shopkeepers were transplants from metro areas. Restaurants followed the current trends, or not, and many thrived. Given the restaurant half-life is equivalent of a Higgs boson particle, some Woodstock eateries set records for longevity. Deanie’s (comic postcard below) and Joshua’s were institutions.

Outside forces continue to churn up new, sometimes welcome, sometimes not, changes for Woodstock. No matter. It will always be Woodstock.

Postcard: “Let’s get a good meal at Deanie’s and look at the weird characters.” Reverse reads: “Deanie’s Restaurant, frequented by celebrated artists, writers and musicians, who appreciate good food.” Art by Jerry Walter. Card not dated.

The Deanie’s site has been Cucina’s Restaurant since 2008. Current photo from their website cucinawoodstock.com.